Figuring out the greatest bubble in history is like asking someone who their favorite child is.

I go back and forth between the South Sea Bubble and 1980s Japan.

The stats from Japan in the 1980s seem to defy the financial laws of gravity:

- Japan made up 15% of world stock markets in 1980. By 1989 it represented 42% of the global equity markets.1

- From 1970-1989, Japanese large cap companies were up more than 22% per year. Small caps were up closer to 30% per year. For 20 years!

- Stocks went from 29% of Japan’s GDP in 1980 to 151% by 1989.

- By 1990 the Japanese real estate market was valued at 4x the value of real estate in the United States, despite being 25x smaller in terms of landmass and having 200 million fewer people.

- Tokyo itself was on equal footing with the U.S. in terms of real estate values.

- The Imperial Palace in Japan was being valued as much as the entire real estate market of Canada.

Japan was trading at a CAPE ratio of nearly 100x which is more than double what the U.S. was trading at during the height of the dot-com bubble. So the stock market was out of control.

But the real estate madness is even more interesting to me because real estate touches so many other aspects of the economy — banks, households, institutional investors, etc.

The biggest reason there was such a hangover in so many parts of our economy following the 2008 debacle is because the housing market was so heavily involved.

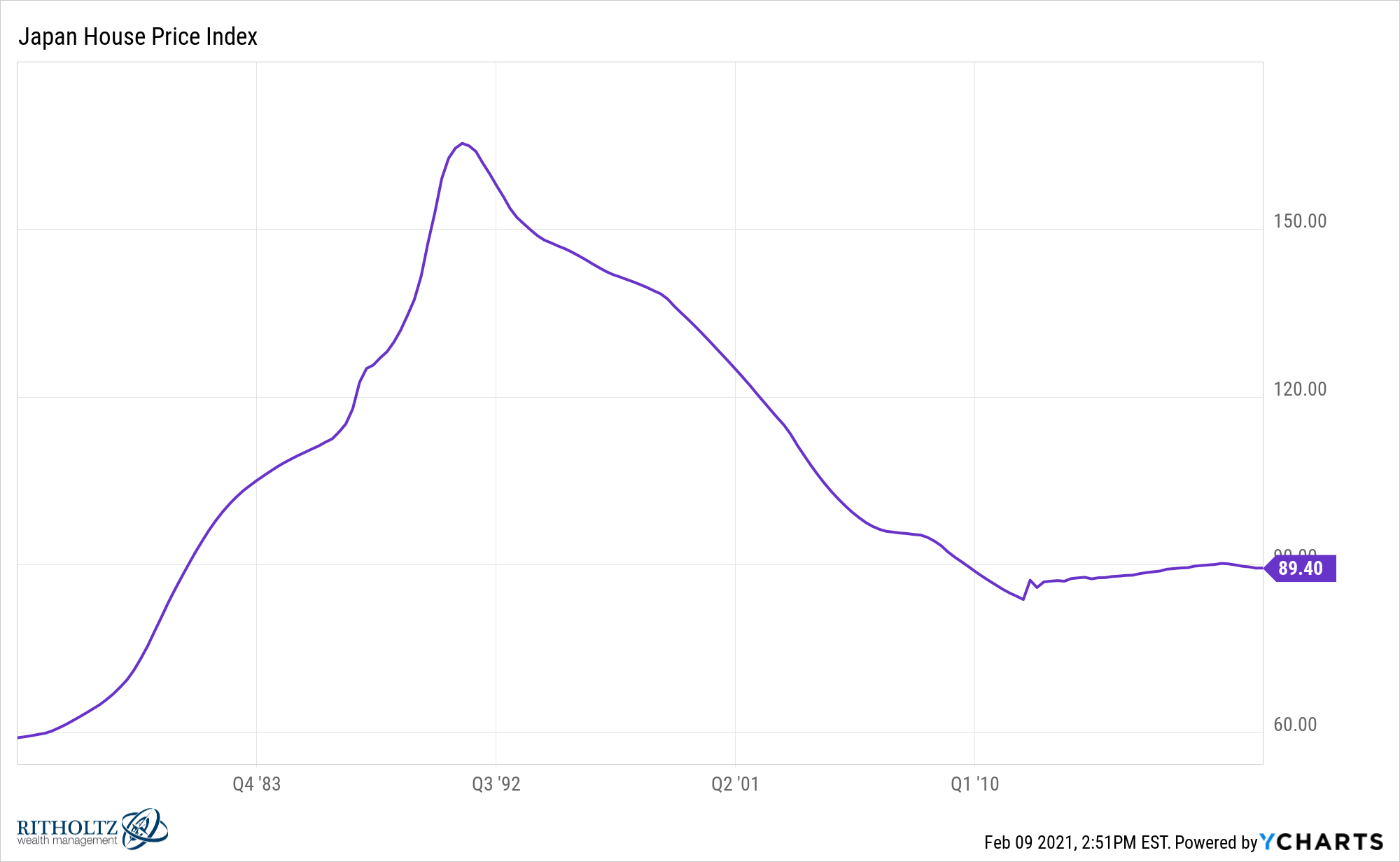

Of course, Isaac Newton showed up eventually, as you can see from Japan’s housing market ever since:

Housing prices in Japan remain down nearly 50% from that late-1980s peak more than 30 years later.

How could these prices possibly ever get so out of whack with reality?

The same way they do in every financial asset bubble in history — people willfully suspended their disbelief.

Christopher Wood wrote about how this suspension in disbelief played out in the Japanese housing market in his book, The Bubble Economy:

Just as they like to dismiss the Bubble Economy as some sort of aberration grafted on to the “real” economy, the Japanese also like to dismiss the astronomical values in their property market as essentially meaningless. The argument goes that property is seldom traded and therefore the values are not real.

Wood explains part of this line of thinking that “values are not real” was partially based on tradition and culture:

For all its high-tech gadgetry and automated vending machines, Japan remains a feudal society at heart whose members, like peasants throughout the ages, believe in the value of land. Behind many a salaryman there is a grandfather or elderly relative still toiling in the fields. Their blue-suited salaried offspring still count their net worth primarily as the dirt on which their prefabricated houses sit.

In Japan virtually all of the value of a property lies in the land, not the building. As a result, buildings are knocked down and replaced with almost reckless abandon.2

I guess since they valued the land so much more than the buildings the assumption was the actual price of the land didn’t matter.

The problem with this line of thinking is the number of people and financial institutions who were given loans on land that rose dramatically in value. The banks issued these loans. Insurance companies bet on the bonds created by them. Households borrowed against them.

So it doesn’t matter if the properties are seldom traded. Those values were real from a financial asset perspective.3

This is going to date me a little but in the 1980s classic Crocodile Dundee, a mugger tries to rob Mick and his lady friend Sue with a switchblade. To which Dundee replies, “That’s not a knife. That’s a knife.”

Ok, so most 1980s movies don’t age well.

But this is the way I feel about many bubble comparisons these days. Here’s the meme:

Now, Japan’s bubble is a ridiculously high hurdle rate when it comes to these types of comparisons. You don’t have to see things get that crazy for markets to completely overshoot.

There are certainly pockets of suspended disbelief right now. There are places where value isn’t real in the current environment.

I’m not good at market predictions because predicting the future is hard. I’m in the camp that every correction is healthy if you’re someone who is still saving money. Down markets are a good thing because they allow you to average in at lower prices and higher yields. And whether down markets are good for you or not, they’re a feature of the stock market.

But it feels like now more than ever a healthy correction is sorely needed before things get out of hand.

It’s way too easy to make money right now.

If this continues things could get out of hand.

And then people would see what an actual bubble looks like.

I hope that doesn’t happen but it’s something you have to prepare for as an investor.

Further Reading:

Why Bubbles Are Good For Innovation

1And this happened while the U.S. stock market appreciated more than 17% per year!

2I should note this book was published in 1992 so I’m not positive this still rings true.

3The aftermath of the Japan bubble has always fascinated me. Wood wrote his book in the early-1990s just after the bubble had burst so I would love to see a follow-up that answers the following questions:

- How in the world did Japan’s crash not take down the rest of the global economy with it?

- How many people could have foreseen the 1990s economic boom in the U.S. following the enormous bust in Japan?

- What has the experience been like for the average saver and investor in Japan over the past 2-3 decades?