Surprisingly, this is not the only time the U.S. government has forced the country into a recession.

The economy wasn’t turned off like it is at the moment, but the Federal Reserve forced the country into a recession in the early 1980s.

From the start of 1980 through the end of 1982, the U.S. economy was in a recession for 22 out of 36 months. It was technically two different recessions, one in the first half of 1980 and another from the summer of 1981 until the end of 1982.

Inflation was the main culprit for this recessionary period but it was technically caused by Paul Volcker and company at the Fed. It didn’t happen without reason.

One dollar in 1970 would only be worth 39 cents by the end of that decade.

Inflation in the 1970s in the United States came in at 7% annually which was more than a percentage point above the annual gain on the S&P 500 during that time.

Things only got worse in 1980, with inflation running at nearly 14%.

Something had to be done to control prices from spiraling out of control.

Enter new Fed chair Paul Volcker, who raised the Fed Funds rate to more than 20% in the early 1980s, with President Reagan’s blessing.

Killing inflation was not appreciated by many people at the time.

The unemployment rate went as high as 10.8% by 1983, the highest rate on record going back to WWII (even higher than it got during the financial crisis).

Binyamin Appelbaum shared the blowback and pain caused in his book The Economists’ Hour:

Factory workers suffered most. Unemployment in the auto industry reached 23 percent. Among steelworkers, it hit 29 percent. And the damage was enduring: a study of Pennsylvania workers who lost jobs in the mass layoffs found that six years later they were still earning 25 percent less than before the recession.

As Americans suffered, they noticed a new kind of pilot was guiding the economy. Auto dealers sent Volcker the keys to cars they could not sell. Home builders sent chunks of two-by-four wooden beams. “Dear Mr. Volcker,” one wrote on a block with a knothole. “I am beginning to feel as useless as this knothole. Where will our children live?” A home builders’ association in Kentucky published a wanted poster for Volcker. His crime: Murder of the American Dream.

Volcker went down as a hero for snubbing out inflation but many people at the time were horrified with his actions.

Over this period there were two stock market drawdowns. In early-1980 the S&P 500 fell around 17%. Then from late-1980 through the summer of 1982, stocks fell more than 27%.

The CAPE ratio in February of 1980 was just 9.0x and that’s before falling nearly 20%. And by November 1980, before falling 27.1%, the CAPE ratio was just 9.7x.

Valuation-focused investors would kill for such fundamentals at the moment but the main reason for these low valuations was the sky-high inflation at the time.

Even low valuations couldn’t protect the stock market from falling.

Many investors assume as long as you buy at low valuations and sell at high valuations you’ll come out ahead. But it’s not always that easy.

Valuations require context. And sometimes valuations don’t tell you everything you need to know about the relative attractiveness of stocks.

This can be especially true during a bear market. In the past, the market has gotten ridiculously cheap based on valuations by the bottom of a bear market. Other times, valuations haven’t cooperated to give investors an all-clear signal.

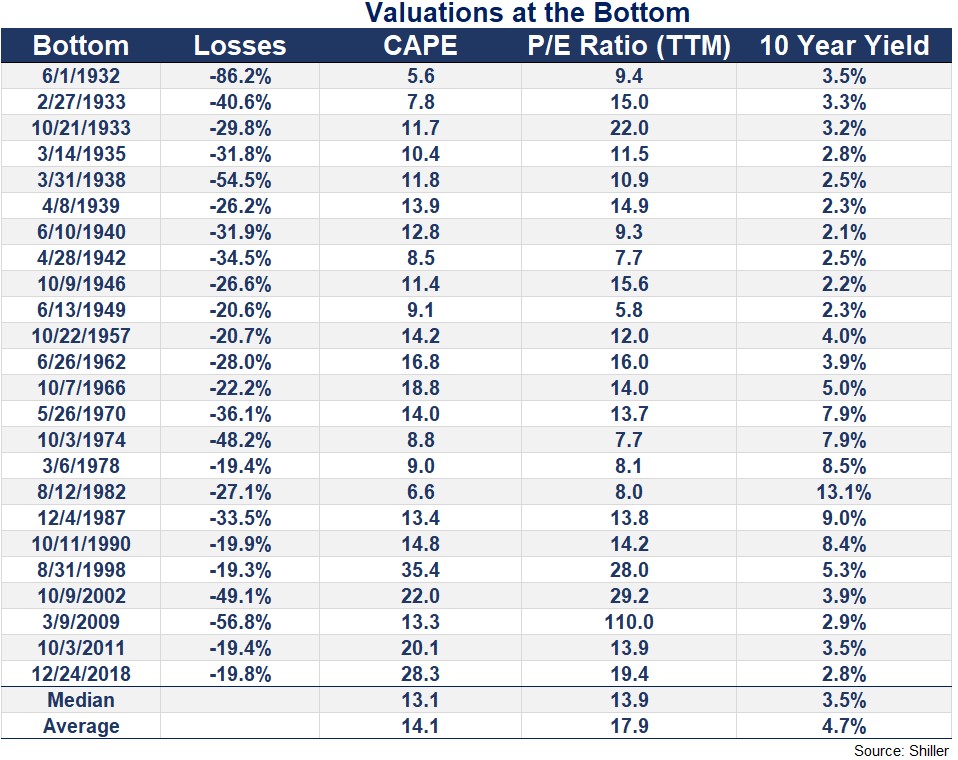

Here’s a look at market bottoms for the S&P 500 from the perspective of drawdowns, valuations and interest rates when stocks decided to stop going down:

Trying to find a clear pattern here is impossible because there is no clear pattern. Way back when stocks typically bottomed at valuations that were well below long-term averages.

Valuations have slowly risen over time while interest rates have gone from low to high to the floor which gives investors an additional variable to consider.

I’m sure many investors look at the valuations seen in the 1930s or 1980s and salivate at the potential to buy stocks that cheaply again during the current bear market.

It could happen. Never say never when it comes to the markets.

But the profile of a bottom in the stock market is just as confusing as a top.

Investing would be easier if you could simply buy at predetermined valuation or interest rate levels and sell at other predetermined levels. The real world doesn’t work like that.

In the past markets have bottomed at relatively low valuation levels, making investing look easy. But they’ve also bottomed when valuations are relatively high.

And interest rates make things even more difficult to handicap. The current level of rates has never been seen before. Does that make stocks easier or harder to prepare for? And how much do historically low rates impact stock valuations?

I would argue that the upward trend in valuations over time paired with the downward trend in interest rates makes it harder than ever to predict what things will look like when stocks bottom out.

Markets are constantly changing. Investors, on the other hand, have similar behavioral issues over time. That makes picking a bottom harder than ever.

Maybe fundamentals will help you nail the bottom. Stranger things have happened.

But it’s far more likely the next bottom will look nothing like the last bottom or any other bottom in history.

During a bear market, valuations may not matter as much as investors assume.

Further Reading:

The Relationship Between Earnings and Bear Markets