The negative interest rate stuff is entering silly town.

This week it was reported a bank in Denmark will be offering negative interest rate mortgages. The bank is paying people to borrow money for a house based on the idea that they are willing to take tiny losses now to avoid potentially bigger losses down the road.

This is bananas but it’s probably not the end of it.

Joachim Fels from PIMCO wrote a piece last week about why negative interest rates shouldn’t be all that surprising. He offered two big secular drivers of this shift:

The two most important secular drivers are demographics and technology. Rising life expectancy increases desired saving while new technologies are capital-saving and are becoming cheaper – and thus reduce ex ante demand for investment. The resulting savings glut tends to push the “natural” rate of interest lower and lower.

This makes sense but we have to be careful when reading opinion pieces about the massive drop in rates around the globe. Many of these stories have been concocted after the fact. It’s not like people were predicting the current interest rate environment years in advance. So much of this could be hindsight bias that’s eventually proven wrong.

But there is someone I’ve been reading for years that laid out the case for a world awash in capital that leads to ridiculously low interest rates in the developed world. William Bernstein wrote a piece called Too Much Capital all the way back in 2005 that more or less drew up the blueprint for the current rate environment.

He showed how, as nations become wealthier, capital becomes abundant. And although we consume more as well, the standard of living is so much higher than it was in the past that it dwarfs consumption (in aggregate):

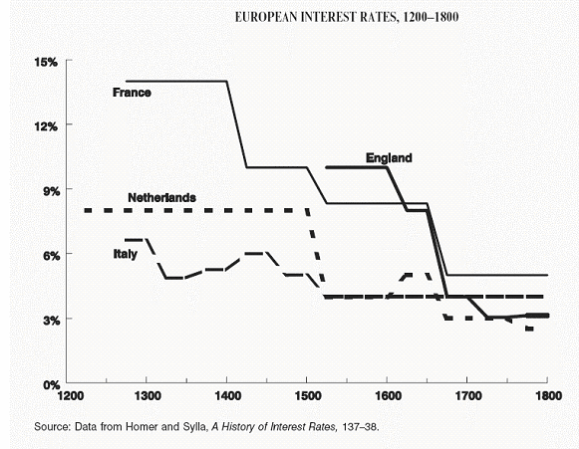

Between 1200 and 1820, for example, per capita GDP in western Europe rose from approximately the subsistence level to three times it—no wonder that interest rates fell so dramatically between these two dates. By the turn of the twenty-first century, it had risen to nearly fifty times the subsistence level, and in the dot-com U.S., to more than sixty-five times.

Here’s the chart:

Bernstein also points out his thoughts on the matter were not an original idea:

The relationship between societal wealth and the cost of capital is not a recent discovery. As early as the beginning of the last century, Irving Fisher observed that where the houses were made of mud and straw, interest rates were high, where they were made of bricks, interest rates were low. And two centuries before that, the director of the East India Company, Sir Josiah Child, observed that “All countries are at this day richer or poorer in exact proportion to what they pay, and have usually paid, for the Interest of Money.” (Admittedly, the point he was making is that causation runs from low interest rates to wealth, and not the other way around.)

The problem, of course, is we’ve got a double-edged sword. On the one hand, we’ve got a standard of living people 100-150 years ago could only dream about. Technology has made our lives better and more convenient in ways most people don’t even understand.1

For investors, this rise in the standard of living and technological innovation means lower returns on their capital. I happen to think this is a trade-off I would make 100 times out of 100 but it’s still a situation investors have to deal with.

Returns likely will and should be lower because (a) interest rates are much lower and (b) valuations are much higher. Valuations don’t have to stay this high forever but it makes sense valuations have been trending higher for years now because we’re wealthier as a society.

This is one of the reasons stocks in emerging markets have lower valuations and more volatility than the U.S. Those markets aren’t as mature (and there’s more corruption and such).

But there are two positives in this situation most investor miss when complaining about lower expected returns:

(1) Living longer gives you a longer runway for money to compound. PIMCO’s Fels discussed the idea of time preference and its impact on interest rates:

However, it can be argued that in affluent societies where people can expect to live ever longer and thus spend a significant amount of their lifetimes in retirement, more and more people demonstrate negative time preference, meaning they value future consumption during their retirement more than today’s consumption.

Obviously, not everyone has this down but retirement basically didn’t exist for people 100 years ago so the fact that we’re living longer had to impact the cost of capital eventually.

The flipside of this, for people who can plan ahead to take advantage, is that we can allow our money to compound for longer. Lower rates of return can still grow your money to vast sums if you allow compounding to take the wheel.

(2) The costs of investing have come down substantially. One of the main reasons interest rates were higher and valuations lower in the past is because the frictions to invest were greater. Bid/ask spreads were higher. Commissions were ridiculously high. The first index fund in the 1970s had an 8.5% sales load every time you bought it.

Investors demanded higher returns to put their money to work because of these higher frictions.

So while gross returns might have been higher in the past, on a net basis things may not be so different going forward. Buying stocks or funds is effectively free at most fund shops or brokerages. Bid/ask spreads, commissions, and fund expenses have come down substantially.

I’m not naive enough to believe low rates or inflation are here to stay forever and always. But the trend seems to be in the direction that rates, and therefore expected market returns, are going lower.

Just remember this is a good thing in the grand scheme of things. It means the world is becoming a better place.

Further Reading:

Investing in a Negative Interest Rate World

1I understand this is not true for all people but overall the trend in poverty is one of progress.