The current retirement system leaves much to be desired.

There are a decent number of people taking advantage of tax-deferred savings vehicles but it’s a fairly small number that ever reaches millionaire status in these accounts.

In Fidelity’s defined contribution plan, there are roughly 157,000 people who have saved at least $1 million in their 401(k). There are another 148,000 people who have saved $1 million or more in an IRA. That’s only 1% or so of Fidelity’s total retirement plan participants.

There’s nothing special about hitting the $1 million mark. Most people will likely never get there (the current number of millionaires in the U.S. is around 5% of the population or 1 out of 20 people) while for some it’s not enough to keep up with their lavish lifestyles.

I wanted to run the numbers to see how feasible it would be for people of different age ranges and saving styles to hit this big round number.

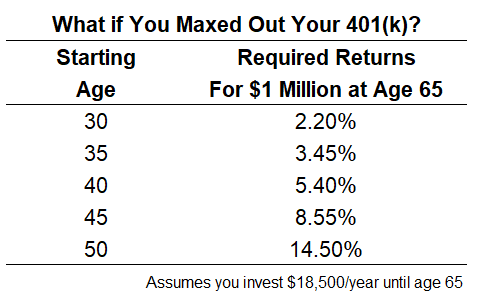

The max contribution limit for 401(k)s at the moment is $18,500 (not including an employer match). Here are the investment returns required to reach a million dollars by age 65:

It’s not a ground-breaking discovery to point out how helpful it is to begin saving at a young age. The required returns to hit $1 million for someone who maxes out their 401(k) in their 30s is a fairly low hurdle rate. Wait to start saving until you’re in your late-40s or 50s and it’s much harder to get to seven figures.

Obviously, maxing out your retirement contributions is not an easy task.

According to Vanguard just 4% of savers in their defined contribution plan who earn $50,000 a year max out their 401(k). For those making between $50k and $100k that number jumps to 11% of participants. And 32% of people making $100k or more max out their tax-deferred savings.

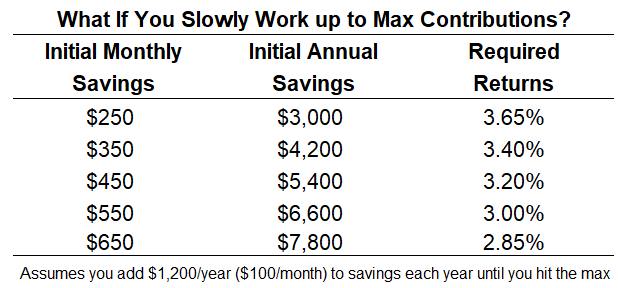

It’s also tough to go from zero to sixty and begin maxing out your retirement account without slowly building up to that level. Very few people max out from day one.

So let’s look at an example of some hypothetical 30-year-olds who save at different levels and slowly increase the amount they save each year until they hit the max (increase by $100/month each year until max is reached). Here are the required returns to hit $1 million by 65:

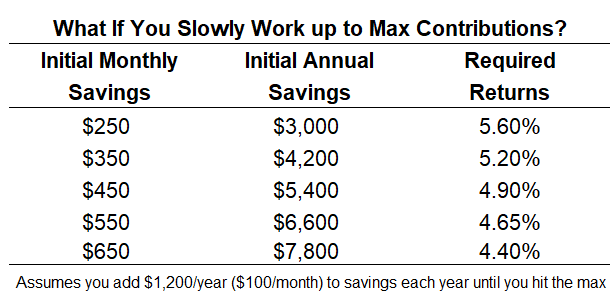

Here’s the same exercise starting at age 35:

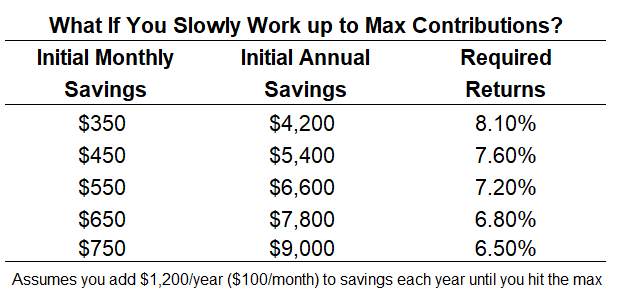

And the same scenario using age 40 as the starting point:

A few observations and caveats:

- Consistently saving money from a relatively young age over time can make up for a lack of investment acumen.

- But consistently saving money in a linear fashion over time is probably one of the hardest things to do because life is inconsistent. If you’re a robot saving up a large nest egg should be an easy feat. Unfortunately, it’s not.

- For all of the worry about lower expected investment returns from current interest rate and valuation levels, the required returns don’t have to be that high for those who put aside some money at an early age.

- These numbers don’t take into account any employer match or the possibility of a change to the contribution limits (the government could always lower the limit or increase it — the limit has roughly doubled since the late-1990s).

- $1 million dollars a few decades out from now obviously won’t be what it is today but I’m guessing that number will always act as a benchmark for a lot of people.

- Unfortunately, not enough people even have access to a 401(k) to take advantage of the tax-deferred savings. It’s estimated that just 14% of employers in the U.S. offer some type of workplace retirement plan to their workers. The fact that more people change jobs these days adds another degree of difficulty as well.

- The numbers I ran here make it seem like it shouldn’t be that hard to save at least $1 million by retirement age. But everything looks easier on paper than in real life, especially when money is involved. Saving, investing and getting your personal finances in order is always more of an exercise in psychology than math. It would be irrational of me to suggest that “everyone” should be able to be a 401(k) millionaire because getting your finances in order is no easy task.

Further Reading:

That Time a U.S. Senator Tried to Actually Me on Twitter