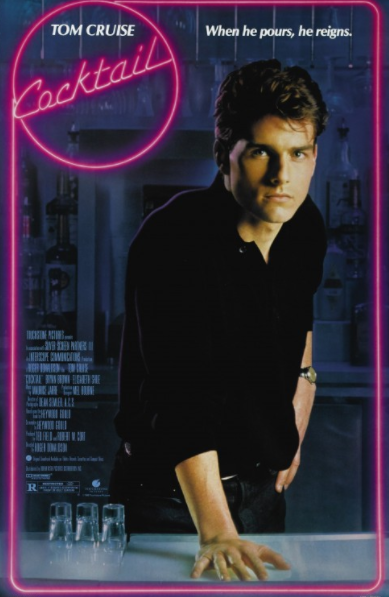

In the classic 1980s movie Cocktail, young Brian Flanagan (played masterfully by Tom Cruise) shacks up with an older woman who basically becomes his New York City sugar momma. They met at a bar in the Jamaica and it was never going to work out but they made a go of it anyways.

When things eventually come to an unceremonious end the woman pleads with him, “Please, I don’t want it to end this way.”

Flanagan responds, “Everything ends badly, otherwise it wouldn’t end.”

This sums up why the phrase “this will end badly” annoys me so much in the investment world. People constantly use this line whenever things are going well. My response is the same as young Flanagan’s — of course it will end badly, otherwise it wouldn’t end.

At some point, this bull market is going to come to an end. I don’t know how and I don’t know when but eventually we will have a crash or bear market. It’s not going to be a healthy correction. People will panic at some point.

This is how things work in the stock market.

Simply acknowledging that you know things will end badly isn’t really helpful; it’s stating the obvious. Many of the people who have been saying this for a number of years now will be issuing ‘I told you so’s’ after the fact and pretending the whole thing was obvious. They’ll even try to convince you they knew the exact reason or reasons for the start of the downfall. It always happens like this.

There’s a huge difference between knowing and profiting in the markets.

In his book, Panic: The Story of Modern Financial Insanity, Michael Lewis sums this up better than I could:

The literature about booms and busts tends to be written in a tone of Olympian detachment by some presumably omniscient narrator with a gift for rendering the folly of man. The writer of these histories is usually amused, wryly; his reader, he assumes, shares his knowingness, understands that markets were ever thus, there is nothing new under the Wall Street sun, etc. Everything, in retrospect, is obvious. But if everything were obvious, authors of histories of financial folly would be rich. They’d spare themselves the trouble of making their living writing books and articles about the financial folly and open hedge funds.

It’s never entirely obvious what is going on inside some boom. Not only does financial history seldom repeat itself; it seldom even rhymes. Financial markets work in free verse, and no matter how much you’ve studied them — no matter how many times you’ve read Charles MacKay’s Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds — you remain at risk of being sucked into the passions of the moment.

Understanding financial history is a huge part of being a successful investor but it’s not enough because with the benefit of hindsight the past always looks too easy. And financial history is no help if it leads to overconfidence in your investment ability to predict the future.

Of course I would have bought stocks following the 1987 crash.

Of course I would have gotten out of tech stocks before the Internet bubble burst.

Of course levering up on real estate was a dumb idea in the mid-2000s.

Of course I would have bought at the bottom in March of 2009.

Hindsight tricks people into believing they would have avoided all the previous mistakes made by other investors. It also makes people forget some of the mistakes they have already made. It’s the everyone-else-is-an-idiot-but-I’m-completely-rational syndrome (aka the Dunning-Kruger effect).

The same thing applies to any behavioral bias. You can read all the Kahneman you want but it’s still not going to help you in the moment. You can’t suppress your natural human instincts.

Everyone is rational, logical, and disciplined when looking at the past. That’s why you never see a poor backtest. The backtest is the easy part. It’s dealing with the forward-test that calls your courage into question. That’s when you find out if ‘stay the course’ or ‘think and act for the long-term’ are more than just phrases.

This is why you need an honest appraisal of your appetite and tolerance for risk before it strikes.

You need the right asset allocation in place that will allow you to stick with it and even rebalance into the pain.

You need to make sure you have the finances outside of your portfolio in order to be able to survive a market downturn and avoid becoming a forced seller.

Basically, you need self-restraint, savings, and the nerve to see a plan through. This is not an easy task but successful investing is emotionally challenging at times.

Right now things seem easy. It won’t last forever. Things will “end badly” but stocks don’t stop trading following a bear market. Life goes on and so will your investments.

It will seem obvious in hindsight but not at the time. So prepare yourself now for this eventuality, whenever it may come.

And if nothing else works, just remember the advice Brian’s mentor, Doug Coughlin, gave him in Cocktail:

Coughlin’s law: never show surprise, never lose your cool.

Source:

Panic: The Story of Modern Financial Insanity

Further Reading:

Ponzi Schemes & Ego

Here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- What happens when your friend’s investments outperform yours? (Irrelevant Investor)

- How luck influences investment success and what to do about it (Of Dollars and Data) see also Playing favorites (Humble Dollar)

- Never give up on people (Reformed Broker)

- Closing the self-awareness gap (Abnormal Returns)

- The Rock for president? I’d vote for him (GQ)

- A simple guide to the end of the boom (Collaborative Fund)

- 13 things to give up to be successful (Personal Growth)

- How to teach kids about financial literacy (A Teachable Moment)

- The back story on the Air Jordan (YIS)