Whenever there’s a sea change in a given industry caused by an upstart, competitor, or new way of doing business there are typically two ways the incumbents can play it:

- They can underreact, stay on the same course, and hope to keep market share.

- They can overreact, overhaul their way of doing business, and hope to play catch up.

My guess (hope?) is that we’ll see plenty of strategy number two by retail and entertainment companies in the years ahead because of the changes caused by Amazon and Netflix in these two areas. This would be a win for consumers if it were to happen.

The investment industry is undergoing its own changes — namely the massive growth in index funds, ETFs, and low-cost investment products. Vanguard’s John Bogle, one of the main people responsible for this revolution, thinks the old guard should try strategy number one. Here’s what Bogle had to say at the recent Morningstar Investment conference in Chicago:

Maintain your fund business as the ‘cash cow’ that it is today, delivering high margins and generous profits, albeit likely at a declining rate. Don’t invest more capital. Don’t cut management fees. Nominal cuts won’t help, and severe cuts would eliminate those cash flows. While fund cash outflows are highly likely to continue, a sharply rising stock market, however unlikely, would help offset the outflows, slowing the declines in assets under management, fee revenues and profits.

In the shortened version of his advice to active fund firms, Bogle said, “Do nothing, just stand there.”

Standing there seems to be what many of the huge active fund firms have decided to do but my guess is we’ll see plenty of overreactions in this space as well in the form of mergers, acquisitions, new product lines, and fund gimmicks to stay relevant.

We’re also seeing overreactions by investors who have been quick to draw conclusions about what it all means before the dust has settled.

Some think this is the end of active management as we know it while others assume it’s just a fad. Some think the rise of passive investing will cause market instability while others assume it will do no harm. Some think there are fewer patsies at the poker table leading to a dearth of alpha opportunities while others assume it will be easy pickings for active investors as more people index.

My view is that these things are never black or white and that it’s far too early to know with any certainty what the outcomes will be. There’s rarely enough nuance or context provided in these arguments because both sides of the aisle seem to portray the other side as being the enemy in the passive versus active debate.

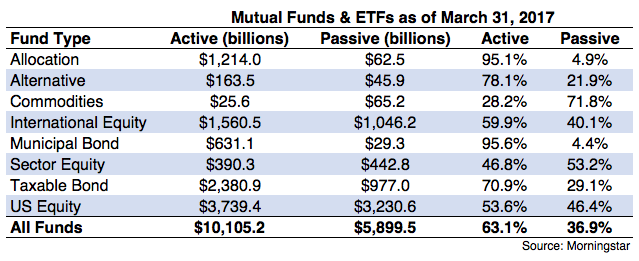

For instance, simply looking at the flows or amount of money in any of these strategies does not tell you anything. My friend Jeffrey Ptak from Morningstar recently ran the updated AUM numbers for me on fund assets in the U.S. which includes both ETFs and mutual funds to give a breakdown by various categories (excluding money market and fund-of-fund assets):

Passive investing gets the headlines lately but it still has a long way to go to catch active in the assets department (there’s an even wider gap abroad). The line that really sticks out here is in U.S. equity funds. It’s getting very close to a 50/50 split between active and passive in this category.

The problem is that this simple breakdown tells you nothing about the investors in these funds. Just because an investment product is labeled “passive” doesn’t mean its investors are. In fact, investors in ETF-based index funds are anything but passive. They’re some of the most active investors out there.

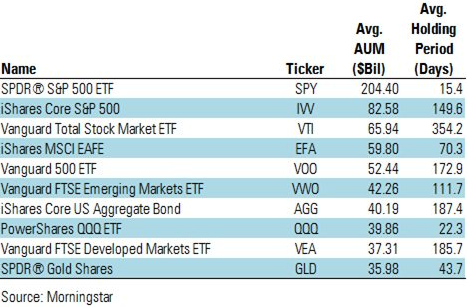

Ptak’s colleague at Morningstar, Ben Johnson, recently tweeted out a list of the top ten largest ETFs along with their average holding period:

The fact that the holding period in this table is listed in days and not years tells you everything you need to know about how active these passive investments really are. These ten funds collectively have nearly $700 billion in assets. The largest fund, SPY, has an average holding period that lasts about as long as an episode of Hardcore History.

I don’t see how you could possibly consider these index products passive investments. There are obviously some investors using them for long-term investing purposes but these funds are also frequently used by hedge funds, traders, and performance chasers alike as hedging vehicles, short-term market exposure trades, and speculation plays.

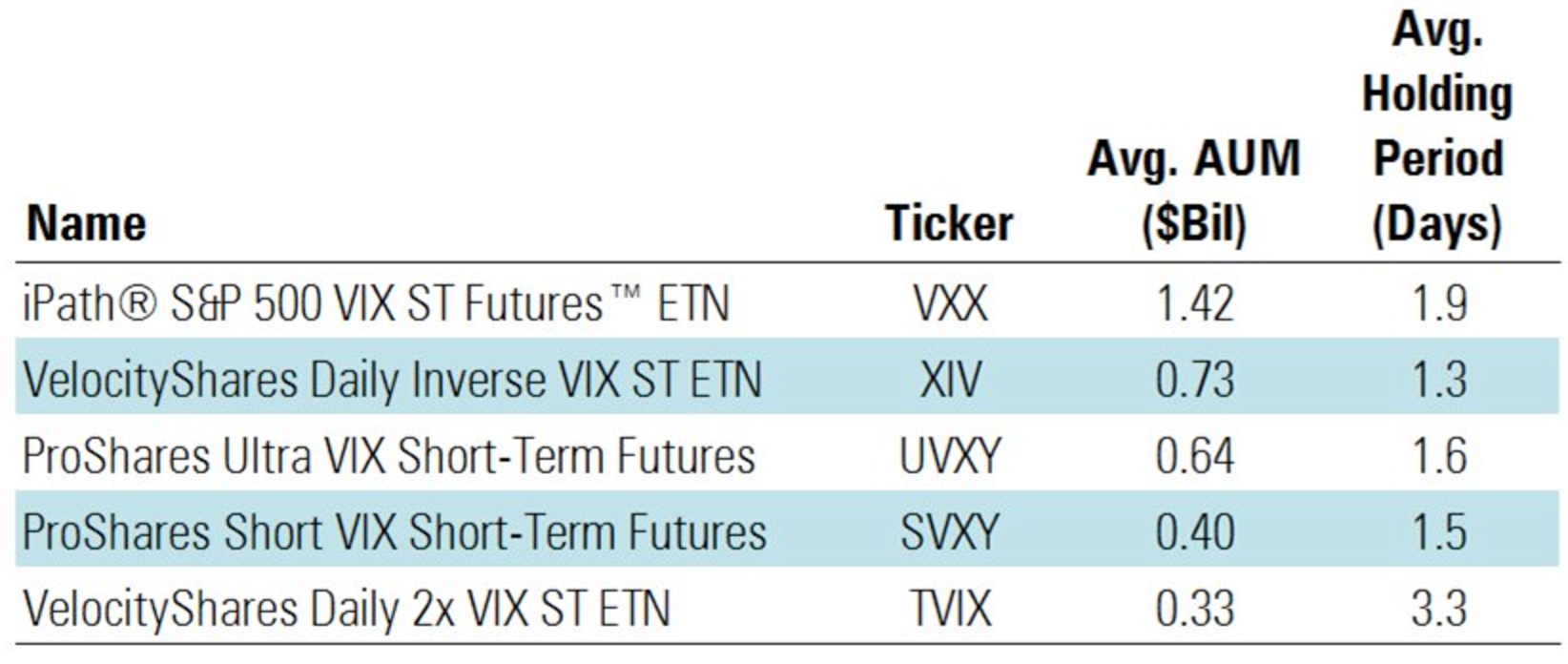

Johnson also shared the holding period information on a group of exchange-traded products which track volatility in one for or another:

These funds may be rules-based but they’re certainly not the preferred asset of a long-term buy and hold investor (nor should they be).

All index funds aren’t good just like all active funds aren’t bad and all index investors aren’t passive just like all non-index investors aren’t active. You can split hairs in the active versus passive debate but it’s worth understanding that you can’t judge a fund or investor by the way they label themselves.

The ETF and mutual fund markets are a lot like the market itself. They’re full of investors, traders, and speculators of all shapes and sizes, each with completely different risk profiles, time horizons, opinions, forecasts, philosophies, views of the world, and investment strategies.

And it’s still way too soon to draw any concrete conclusions about what the growth in “passive” investing will mean for the markets, how far it’s going to go or what the market impact will be.

Further reading:

Playing Devil’s Advocate on Index Funds

Be sure to follow both Jeff and Ben on Twitter:

@MStarETFUS

@syouth1