Henry Ford started his famous assembly line in 1913 for mass production of the Model T. It’s estimated that this idea decreased the time it took to build a car by close to 80%.

In order to keep the prices relatively low, Ford made every car the same so they could all be produced on the assembly line in an efficient manner. In fact, until 1925 the only color the car came in was black. There were no other choices like we have today in terms of custom features.

Then in the 1920s companies figured out the way to get people to buy their products over and over again was to become more creative with design and the number of available choices.

In his intriguing new book, Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity, Derek Thompson tackles the idea about what makes something popular and he touched on cars during this time frame. He talked about how Ford’s competitors at GM changed things up:

Executives like Alfred Sloan, the CEO of General Motors, recognized that, by changing a car’s style and color every year, consumers might be trained to crave new versions of the same product. This insight—to marry the science of manufacturing efficiency and the science of marketing—inspired the idea of “planned obsolescence.” That means purposefully making products that will be fashionable or functional for only a limited time in order to encourage repeat shopping trips. Across the economy, companies realized that they could engineer turnover and multiply sales by constantly changing the colors, shapes, and styles of their goods. Technology enabled choices and choices created fashion—that perpetual hype cycle where designs and colors and behaviors appear suddenly cool and then suddenly anachronistic.

Basically, this is how consumerism itself was born. Companies released slightly modified versions of existing products to get people to buy them more frequently. This is what our consumer culture is built upon.

Thompson discussed research performed by Paul Hekkert, a professor who specializes in commercial design and how it’s impacted by psychology. Hekkert says that humans seek out familiarity but also enjoy the thrill of a new challenge. Here’s Thompson:

This battle between discovery and familiarity affects us “on every level,” Hekkert said—not just our preferences for pictures and songs, but also for ideas and even people. In studies, Hekkert and his team asked respondents to rate several products, like cars, telephones, and teakettles, for their “typicality, novelty and aesthetic preference”—that is, for familiarity, surprise, and liking. The researchers found that neither measure of typicality nor novelty alone had much to do with most people’s preference; only taken together did they consistently predict the designs that people said they liked.

Thompson concluded that people are both attracted to new things but resistant to that which is unfamiliar. So we’re drawn to a combination of familiarity and novelty.

In many ways, this is the paradox of choice that investors are faced with when trying to handicap the seemingly endless number of available investment products. We want to buy funds and strategies we’re familiar with but when new versions come out they can be extremely enticing.

The options available for investors have never been better but the sheer number of fund choices can be overwhelming. And the financial industry isn’t going to stop in its pursuit of the next best thing for investment consumers to buy.

There’s been plenty of press in recent weeks on the results from the latest SPIVA Scorecard, which is a periodic report put out by Standard & Poors that compares active mutual fund performance to that of their benchmarks or indexes.

The latest numbers are another black eye for the active management complex given that the first 15-year numbers SPIVA has ever calculated show that 92% of large cap, 95% of mid cap and 93% of small cap managers failed to beat their respective benchmarks.

My first reaction when seeing these numbers was this: How is it even possible such a small fraction of professional investors can accomplish their sole job?

Costs are an obvious hurdle and increased competition has made it much harder to outperform in today’s markets but there’s another variable that has a lot to do with this that was documented in the SPIVA report:

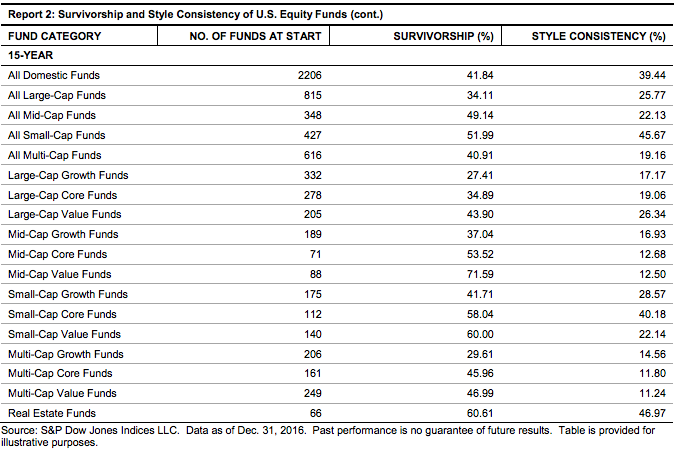

Funds disappear at a significant rate. Over the 15-year period, more than 58% of domestic equity funds were either merged or liquidated. Similarly, almost 52% of global/international equity funds and 49% of fixed income funds were merged or liquidated.

Here’s a table that illustrates this fund graveyard:

These stats are crazy but make much more sense when framed in terms of consumerism and popularity. It would be easy to place all of the blame on the financial industry for continuously rolling out funds year after year in hopes that a few of them will stick but that’s pretty much the way things work in most product-centric business models.

The business model for many industries — mutual funds, venture capital, book publishing, movies, TV — are predicated on throwing a bunch of stuff against the wall in hopes that a few big winners emerge to offset the losers.

In the fund industry, this just means a larger pool to choose from, meaning it will be much harder to pick the winners because so many funds will be complete and utter failures.

As long as investment consumers are willing to chase investment fads and past performance, fund firms will roll out new funds in hope of a few of them becoming big winners. The rest will fall by the wayside, never to be heard from again…

Sources:

Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity

SPIVA U.S. Scorecard