In many ways the stock market makes no sense. You would assume that half of all stocks would outperform a market index while the other half would underperform. Then all you would have to do is pick from the top half and avoid the bottom half, make massive amounts of money and go buy an island somewhere.

Unfortunately, the stock market doesn’t follow a normal bell-shaped curve. Active investing may be a zero-sum game, but picking individual stocks is not. It doesn’t work out that half of all stocks outperform and half of all stocks underperform. There are huge tails when you look at the extreme over- and under-performers in the market.

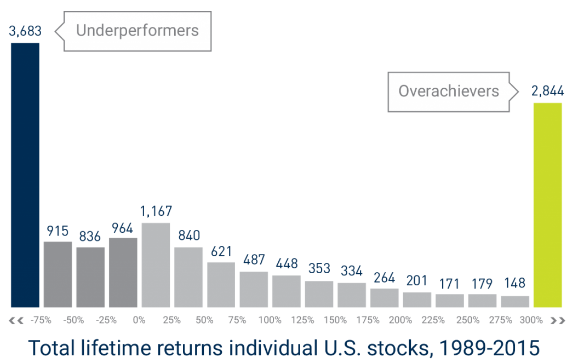

This is exactly what Eric Crittenden at Longboard Funds did in a recent blog post. This visualization of the winners and losers in the stock market since 1989 is fascinating:

Here are the stats behind this excellent chart:

We analyzed 14,455 active stocks between 1989 and 2015, identifying the best performing stocks on both an annualized return and total return basis.

Looking at total returns of individual stocks, 1,120 stocks (7.7% of all active stocks) outperformed the S&P 500 Index by at least 500% during their lifetimes. Likewise, 976 stocks (6.8% of all active stocks) lagged the S&P 500 by at least 500%. The remaining 12,404 stocks performed above, at or below the same level as the S&P 500.

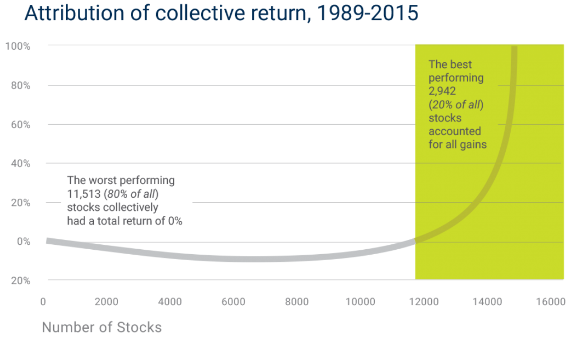

I think this data may come as a surprise to many. Over 40% of all stocks during this period ended up with a negative return. And the winners in the stock market are a much smaller group that account for the entire gain over this period:

These numbers are staggering — 20% of all stocks have accounted for the entire gain over this time frame, meaning the remaining 80% have collectively given investors no return. From 1989-2015 the S&P 500 was up almost 1200% in total. The majority of that gain came from a small number of stocks while the rest were more or less worthless.

There are a few different ways you could choose to look at this data:

- Try to avoid the losers and pick the winners.

- Own the whole thing and benefit from the huge impact that the winners give you.

- The S&P 500 is basically a momentum strategy.

Momentum investors cut their losers and let their winners run. In a roundabout way, that’s exactly what the stock market has done over time. My friend Lawrence Hamtil recently shared a stat on his blog that illustrates part of this equation:

Compared to 2004, more than a fourth of the companies then in the S&P 500 have “been acquired, taken private, or gone bankrupt,” though there have been hundreds of IPOs since.

The very nature of a market-cap weighted index means that the performance will be driven by something of a winners-take-all scenario. The cream rises to the top and the losers tend to fall by the wayside.

Now, is it possible to avoid the losers and only invest in the winners? Sure, anything is possible. Is it probable? Technically, based on this data it’s a low probability strategy. Obviously, many of the companies in that 80% group were smaller, more risky companies that you would expect to fail. Not every business is meant to succeed over time. And there are ways to screen for quality and valuation that can give you better odds of success at avoiding the worst of this group.

But one of the reasons the S&P 500 is so hard to beat is because it has a built-in mechanism to let the winners ride by the way it’s constructed. By our very nature we have a tendency to hold onto our losers and sell our winners too quickly. The S&P 500 or any systematic strategy doesn’t have these same issues holding them back. Can you imagine owning stocks like Apple, Amazon, Google or Facebook as they continued to rise over the years? How many of us would have had the ability to hang on as those gains compounded and the market caps kept rising?

Buying during a bear market is probably one of the most difficult things an investor can do, but staying invested as stocks rise may be a close second. There are constant temptations to “take money off the table” or “de-risk your holdings” after a nice run-up. It’s not easy to allow compounding to occur without getting in the way and screwing things up.

I like to say that index funds are nothing special — they’re systematic, disciplined, rebalanced occasionally, transparent, low-turnover, low-cost, and low-maintenance. Probably the biggest benefit an index has over a human is the fact that it has a disciplined process by default. It’s hard to compete in the markets if you’re not disciplined.

Sources:

Defense Wins Championships (Longboard)

You Can’t Have the Creative Without the Destruction (Fortune Financial)

Further Reading:

Why Momentum Investing Works