The Great Financial Crisis was missed by such a large number of pundits, economists and investors that during the ensuing recovery we’ve seen a huge influx in the number of people trying to predict a the next downturn. People desperately want to call the next big one before it hits.

First it was fears of a double dip recession (that never came). Then we were told we were already in a recession in 2011 (also didn’t happen). Next oil or the dollar or emerging markets or China was going to lead to a recession. Eventually one of these predictions will be right as economic expansions don’t last forever.

In the meantime, we have a new recession that’s much easier to track with real-time data — the dreaded earnings recession. Here’s Savita Subramanian from Bank of America recently describing the current earnings recession that has people worried:

Publicly traded companies have seen negative earnings growth two quarters in a row and there are no fundamental underpinnings for the rally, Savita Subramanian, BofAML’s head of U.S. equity and quantitative strategy, said on CNBC’s “Fast Money” this week.

“We are in a profits recession. There (are) no two ways around it,” said Subramanian, whose S&P 500 price target of 2,000 is among the lowest on Wall Street. She is also concerned about how Federal Reserve monetary policy could affect stocks.

“You have the Fed embarking on a long, slow tightening cycle. Tightening into a profits recession doesn’t sound like anything to throw a big party about,” she said.

I’m not trying to downplay a drop off in fundamentals. Falling earnings could be a harbinger of bad things to come in the markets. As we’ve been warned about for the past 3 or 4 years now, this recovery is getting a little long in the tooth.

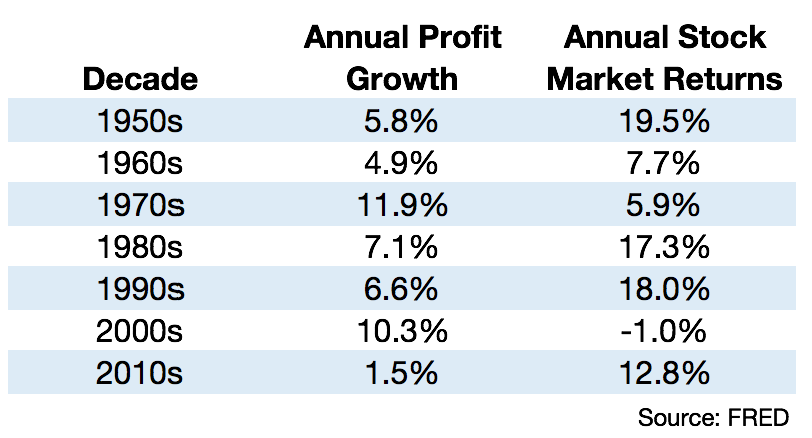

One of the biggest problems in the world of finance is that people make proclamations without backing it up with evidence. So I wanted to see what the historical relationship looks like between profit growth and stock market returns. Using Federal Reserve data on corporate profits, I looked back at the historical growth rate of profits by decade and compared them to that decade’s stock market returns (using the S&P 500):

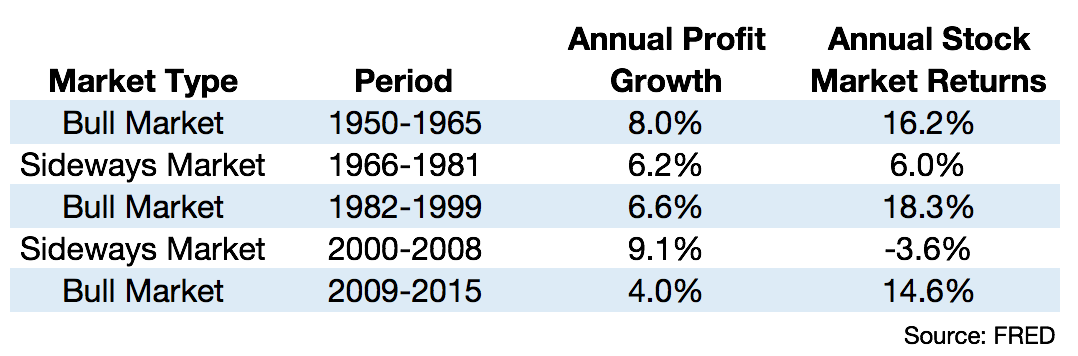

Now let’s break things down even further by market type:

(Although the S&P 500 was up 6% per year in the 1966-1981 period, many consider this a sideways market because the Dow went nowhere from a price perspective and once you take inflation into account real returns were basically zero.)

There’s really not much of a discernible pattern that can be detected here. High profit growth has led to both high and low stock market returns throughout the post-WWII period. There were also times of low profit growth with high stock market returns.

The greatest profit growth was seen in two of the worst-performing stock market decades — the 1970s and 2000s. But those periods were markedly different as the 70s saw sky-high inflation with rising interest rates while the 2000s had low inflation and falling rates.

After accounting for inflation, the 1980s only saw profit growth of roughly 1.6%, but stocks returned more than 17% per year (12% real). The 1950s and 1960s saw one of the greatest bull markets of all-time, but profit growth was basically average. Profits growth has been non-existent during the latest bull market cycle, but stocks are up gangbusters anyways.

This all really comes down to the problem with single variable analysis. You can never look at a single factor in isolation and use it to tell you exactly what’s going to happen with the stock market, even something as important as profit growth. There are so many other factors to consider here — inflation, the economic environment, allocation preferences, demographics, interest rates, profit margins, etc. Then you have to consider the all-important question of how much are investors willing to pay for current or future profits?

I’m not saying that profits aren’t important to the stock market. They are. Over this entire period since 1950 earnings have grown an astonishing 8000%+ or just shy of 7% per year. We need to see corporate earnings growth so companies can increase wages, invest in capex, pay out dividends and buyback shares.

When the next recession hits we will see profits contract and the stock market will likely go into a bear market. But for investors trying to figure out what’s going to happen in the coming cycle, the link between profit growth and stock market performance may not be as strong as some would have you believe.

Maybe the biggest takeaway here is that investors have a hard time figuring out how much to pay for future profits.

Now here’s the stuff I’ve been reading this week:

- 100 year old investment advice (Novel Investor)

- Some things Morgan Housel is pretty sure about (Motley Fool)

- Before you trash smart beta… (Irrelevant Investor)

- 3 mistakes investors make that hurt their performance (Cordant)

- Why full disclosure isn’t always enough (A Teachable Moment)

- The problem with chasing momentum (Pension Partners)

- A true story about investing vs. paying off the mortgage (Monevator)

- Tax efficiency in action (Fortune Financial)

- Stupid things people do to increase their tax refund (Big Picture)

- Social media: The cornerstone of financial firms in the 21st century (CFA Institute)

- Valiant Evergreens – No Trees Grow to the Sky (Gordian)

Why does the return have to coincide directly with the profit growth? Starting valuation is a factor too… I’m impressed, looking at the first table, how little change there is in profits. There’s some, yes, but not much compared to the change in market returns. But that just means returns, over the short run, don’t necessarily reflect reality…. Or, to say the same thing, they’re also affected by starting valuation….. It’s profit growth (or, more precisely, profit-per-share growth) and starting valuation that matter….

Apparently, it does not have to. See the ’00’s. Maybe the market is making up now for lack of progress in the ’00’s when profit growth was approximately as high as it has ever been over a decade.

As for worry over the Fed embarking on a long, slow tightening cycle, I do not see it. The economy has been very slow to grow for over 10 years and federal debt is at record highs. Until our economy catches fire and/or the federal debt is well lower than current level, rates are going nowhere, regardless of “big talk” by FOMC folks.

Similar to GDP growth as well. It’s fairly stable over time but obviously stock returns are not.

Right, but then the conclusion isn’t that earnings growth (or EPS growth) has nothing to do with stock returns. Over the long run it does…. The issue is that starting valuation (what you’re paying for current earnings and future earnings) matters too for the next decade or so.

This has always provided the best decomposition of returns I’ve seen —

http://www-stat.wharton.upenn.edu/~steele/Courses/956/EquityPremium/ArnotBernsteinPremium.pdf

My gut tells me that lower profit growth would be a leading indicator for stock market returns rather than a coinciding occurrence as shown in your first table. Although that is just my gut and you addressed the problem with data-less claims rather poignantly.

I think the key point you make is not basing a conclusion on a single variable analysis. I find most analysis on what happens to returns when XXX happens totally useless – it lacks context and due to the small number of observations it lacks any statistical validity. Good analysis is much more nuanced and takes the economic & market context into account. At the end of the day the starting valuation is usually the greatest determinant of long-term (say 10 year) returns – earnings growth and income generation are a lot more stable and predictable.

Yup, one of the biggest problems with many people’s analysis is the fact that there’s no context applied. Historical numbers help but they don’t exist in a vacuum and every time is just a little (or a lot) different.

Ben, thanks for this excellent article, I had not previously read about the lack of correlation between corporate profits and stock prices; it is certainly not intuitive. Yes, context (otherwise known as the investing environment) is just as important as any other factor. An important contextual consideration are the alternatives to stocks. Right now, cash loses money after inflation, bonds roughly break even, and commodities are in a prolonged slump. Many investors have concluded that stocks are the only place that they can make money, which increases aggregate demand for them, even if profits are not growing. Context can sometimes overwhelm any single other factor.

Yup as I like to say — every time is different and there are always different factors to consider in any market cycle.

Would be interesting to factor in another column: debt levels (both corporate and personal).

We are definitely in for lower market returns, and most probably a bear market, but that is much more to do with exceptional easy policy fizzling out (a tightening cycle is bound to be really slow also), not firm profits, which may or may not be < 4% of 2008-15.

Try doing the analysis with multiples AND earnings growth.

I wonder how much of recent earnings growth is as a result of financial engineering, work force adjustments and technology, as opposed to actual growth in demand. With only anecdotal evidence to support my opinions, my suspicion is that real growth has been flat to modest. As a result, as the effect of other tools to grow earnings has diminished, earnings have inevitably gone flat to negative.

Financial engineering can’t really make earnings grow, just earnings per share. This is total earnings. And I think if you talk about technology then it’s having more of an effect on GDP measurements than anything.

Agreed. But most people (and the market) doesn’t care about the components of “earnings”, just that they exist and keep growing.

A firm can only grow so far on non-organic earnings (e.g. it can’t buy back ALL of its shares), so it’s almost common sense that earnings will be lower in the future. If the market returns beat earnings, that’s your degree of speculation.

I think your analysis is flawed for a number of reasons. Firstly you take the view of a buy and hold investor, and ignore the goals of other market participants such as speculators. Secondly your aggregation of time periods will definitely mask huge falls or rallies in the value of the markets during the time frames you have quoted. Lastly we all know that since the last financial crisis assets prices especially those of equities have been under heavy manipulation from central bank monetary policy. The underlying fundamental behind equity prices is forward earnings and the markets can only ignore it for so long. Some time soon enough the boy who cried wolf will have to face up to it.

This is what value investor breach its how much you pay that determine your return. This also explain why value works with low or negative growth companies.