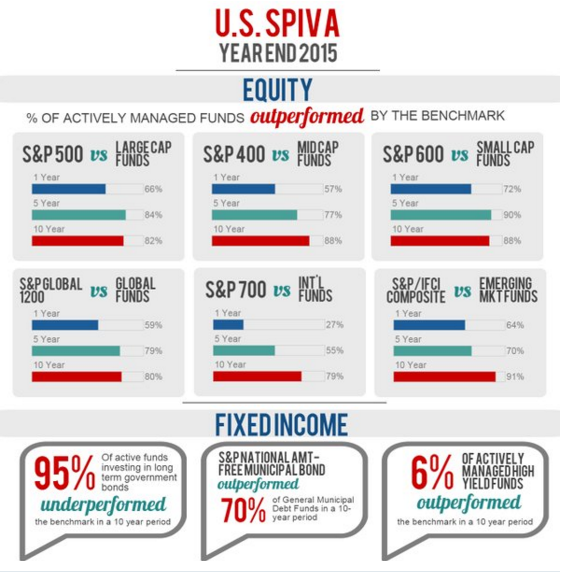

The latest SPIVA numbers are out and once again it doesn’t look too pretty in terms of active management’s ability to outperform their benchmarks:

The passive management revolution, the zero-sum nature of investing, the fact that markets are so competitive these days and the high cost of active management are the prime suspects for these latest results. But I also think there may be another culprit that is hurting active manager performance — benchmarking.

Not only are investors far too worried about peer comparisons, but they also spend far too much time worrying about how their portfolios or funds perform against a stated benchmark. The outcome from a benchmark-centric fund industry is a glut of high-priced closet index funds that are more worried about their positioning in relation to an index than they are about finding the best investment opportunities.

Most investors have a hard enough time outperforming their own fund holdings because of poorly timed purchases and sales but benchmarking is a big deal in the investment management industry.

For the CFA exams, I was taught the SAMURAI acronym to remember what constitutes a legitimate benchmark:

- Specified in advance (preferably at the start of the investment period)

- Appropriate (for the asset class or style of investing)

- Measurable (easy to calculate on an ongoing basis)

- Unambiguous (clearly defined)

- Reflective of the current investment opinions (investor knows what’s in the index)

- Accountable (investor accepts the benchmark framework)

- Investable (possible to invest in it directly)

I know for a fact that many investors don’t adhere to these simple rules (there’s no law that says they have to) when creating their benchmarks, but I believe they represent a good starting point for performance measurement.

I understand the need for benchmarks. In a sense they represent the opportunity cost of your capital. A good benchmark can allow an investor to understand their investments in terms of the following questions:

- Are we taking too much (or not enough) risk to earn these returns?

- Is the fund doing what it’s supposed to do?

- Is there a cheaper, better and easier way to gain this exposure (i.e., invest in the index)?

- Why did we deviate from the benchmark?

- Is this type of tracking error normal or is something wrong with this fund or strategy?

Benchmarks can be a useful attribution tool to check performance and risk after the fact, but they should not drive how you invest (unless of course you’re simply investing in the benchmark portfolio — hence no need for benchmarking).

It’s a mistake to let the benchmark dictate how you invest or the types of risks you’re willing to take. You don’t choose a benchmark and then figure out how to invest within that benchmark. You figure out how to invest and then you make sure you have the correct form of performance measurement for your investments.

The thing most investors miss is that their true benchmarks aren’t so easily quantifiable because they’re mainly long-term in nature — basically, are you on track to meet your goals and objectives? This has almost nothing to do with over- or underperformance in terms of beating a market-based benchmark.

The best form of benchmarking can help improve communication and understanding between an investor and their portfolio managers, funds or advisors. Performance measurement doesn’t necessarily provide all of the answers, but it does help identify the right questions investors and advisors should be looking into together.

They can help determine things like the correct time horizon to pay attention to, how much risk an investor is willing and able to take and how different they would like their performance to be from the market indexes over various time frames.

Benchmarks can act as a good starting point for education to show clients what’s contributing to or detracting from portfolio performance. Performance provides the narrative to communicate an advisor or portfolio manager’s ongoing process.

Unfortunatley, many bad actors in the finance industry use the wrong benchmarks or simply blame someone else for their poor performance. Possibly the best sign of a good steward of your capital is when someone is completely open and honest about why they are underperforming their stated benchmarks.

Performance will always be the main measuring stick investors look to for confirmation that their investments are living up to their expectations. But in a world where it seems that opportunities for alpha are becoming scarcer every year investors have to keep in mind the intangible benchmarks, as well.

It may not fit the CFA Institute criteria, but I believe that one of the best benchmarks you can hold someone to is whether or not they do what they said they were going to do for you. There’s something to be said for a person or firm who explicitly sets reasonable expectations up front and then lives up to those expectations by following through with their actions.

Further Reading:

Goals-Based Investing