“The stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient.” -Warren Buffett

The Wall Street Journal highlighted a new study showing that the median investor spends just six minutes researching a stock before buying it.

It’s no wonder the average holding period for a stock has dropped from roughly 8-10 years back in the 1950s and 1960s to just a few months today.

If you don’t know much about what you own it’s going to be hard to hold onto it for very long if it doesn’t make you rich overnight.

This short-term mentality is the antithesis of Warren Buffett, who stepped down from his role as CEO of Berkshire Hathaway this past weekend at the ripe old age of 94.

Buffett’s longevity is impressive in many ways.

Compounding the share price at 19.9% per year for 60+ years is otherworldly. A total return of more than 5.5 million percent is hard to fathom.

Buffett first bought American Express shares in 1964. Berkshire Hathaway took its first stake in GEICO back in 1976. He’s held Coke since 1988.

I learned early on in my investing career that I would never be a stock-picker like Buffett but I immediately latched onto his views on investing for the long-term.

In the most recent meeting he said “Nobody knows what the market is going to do tomorrow, next week, next month. But they spend all their time talking about it, because it’s easy to talk about. But it has no value.”

I know why people talk about the short-term so much — it’s entertaining. But he’s right that it has no value. Most of the stuff you need to know about investing is evergreen.

Buffett has been preaching this stuff for years.

I’ve been perusing Buffett & Munger Unscripted by Alex Morris, a book that organizes thirty years of insights from Buffett’s annual shareholder meetings.

Here’s a good passage from the 1994 meeting:

I bought my first stock in April of 1942 when I was eleven. The prospects for World War II didn’t look so good at the time; the U.S. was not doing well in the Pacific. I’m not sure I calculated that into my purchase of three shares, but just think of all the things that have happened since then. Atomic weapons, major wars, presidents resigning, massive inflation at certain times, all kinds of things. To give up what you can do well at because of guesses about what’s going to happen in some macro way just doesn’t make any sense to us.

If your time horizon is measured in decades you’re going to be forced to deal with some unpleasant conditions from time-to-time. That’s life and long-term investing.

I liked this one about risk from that same shareholder meeting:

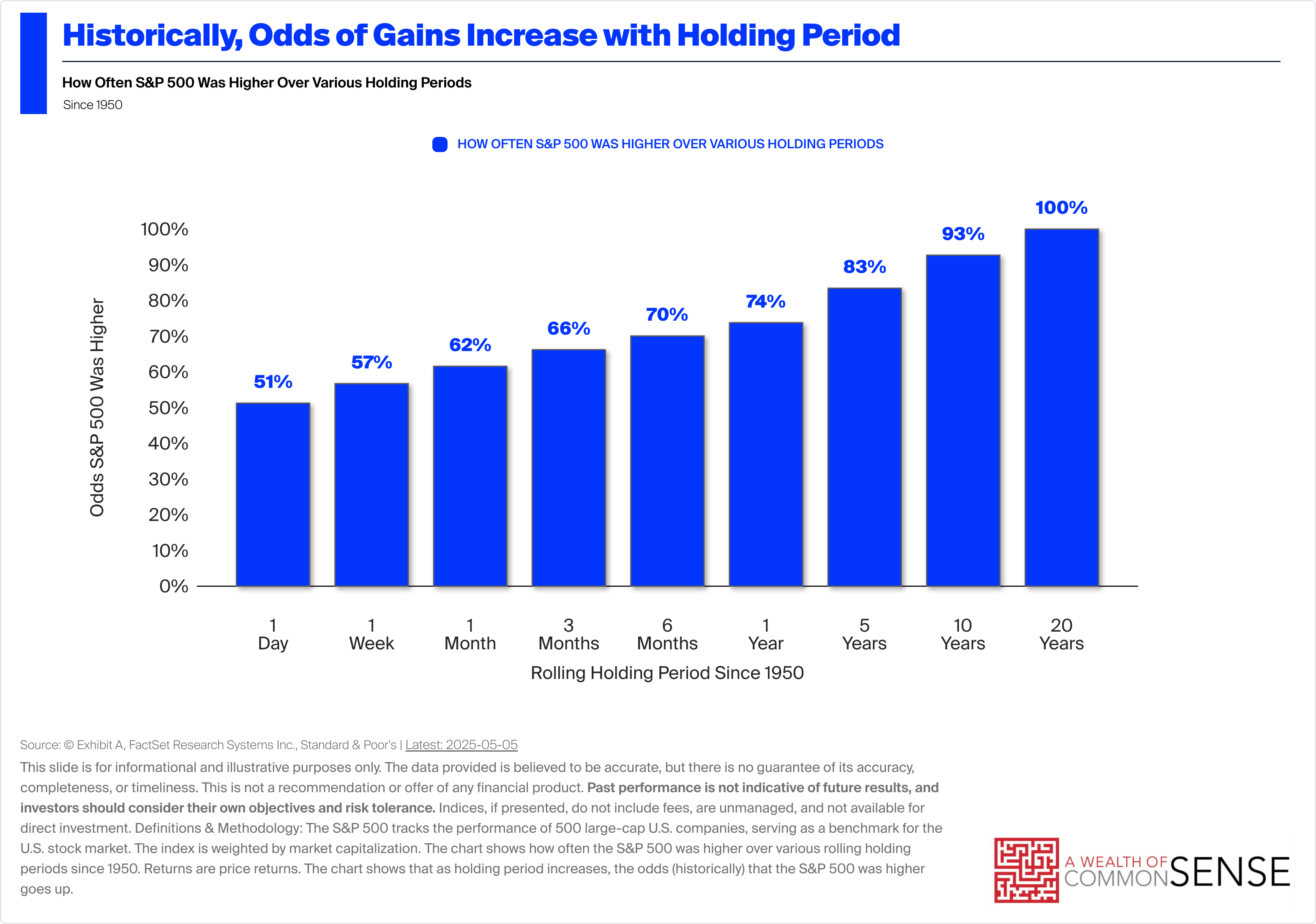

We define risk as the possibility of harm or injury. And in that respect, we think it’s inextricably wound up in your time horizon for holding an asset.

It’s impossible to offer anyone investing advice if you don’t understand their risk profile and time horizon. Extending your time horizon does not guarantee specific results. There can be poor outcomes over 10-20 year periods.

But your odds of success are vastly improved the longer you stay in the game:

The reason it’s hard to win in the short-run is because the market is more unpredictable.

In 1999, Buffett spoke about compounding:

Compound interest behaves like a snowball on sticky snow. The trick is to have a very long hill, which means starting very young or living to be very old.

Of course, thinking and acting for the long-term is easier said than done.

This one from Buffett during the 2020 annual meeting talks about the psychology of buying and holding stocks for the long-run:

I’m not recommending that people buy stocks today, tomorrow, next week, or next month. It all depends on your circumstances. You shouldn’t buy stocks unless you expect, in my view, to hold them for a very extended period, and you are prepared financially and psychologically to hold them the same way you would hold a farm and never look at a quote — you don’t need to pay attention to it. You’re not going to pick the bottom and nobody else can pick it for you.

If you can’t handle it psychologically, then you really shouldn’t own stocks because you’re going to buy and sell at the wrong time.

Buffett is like a walking computer but it was his temperament that allowed him to compound for years on end. At the 2002 meeting he talked about the importance of rationality over brains:

There’s no reason you need a high IQ. Temperament, however, is enormously important; it may be innate, it may be learned, it may be intensified by experience or reinforced in various ways. You have to be realistic. You have to define your circle of competence accurately. You have to know what you don’t know, and not get enticed by it. You have to have an interest in money, I think, or you won’t be good at investing. But if you’re greedy, it’ll be a disaster, because that will overcome rationality.

Investing for the long-term is simple but not easy.

Michael and I talked to Morris about Buffett and his new book on Animal Spirits recently:

Further Reading:

My Favorite Warren Buffett Shareholder Letter