A reader asks:

I don’t work in finance but I know enough math to get me into trouble (I’m an engineer). All else equal, a higher discount rate should mean a lower present value of future cash flows. I know all is not always equal but with rates rising again and the prospect of higher for longer now firmly on the table, shouldn’t that be a headwind for stocks? What am I missing here?

Good question.

Finance theory does state that the present value of an asset is the future stream of cash flows discounted by a reasonable rate of interest.

If PV = CFs / (1+rate)time and the rate goes up, all else equal, the present value should go down.

The problem with this line of thinking is there is a huge difference between theory and reality. Plus, all is rarely ever equal.

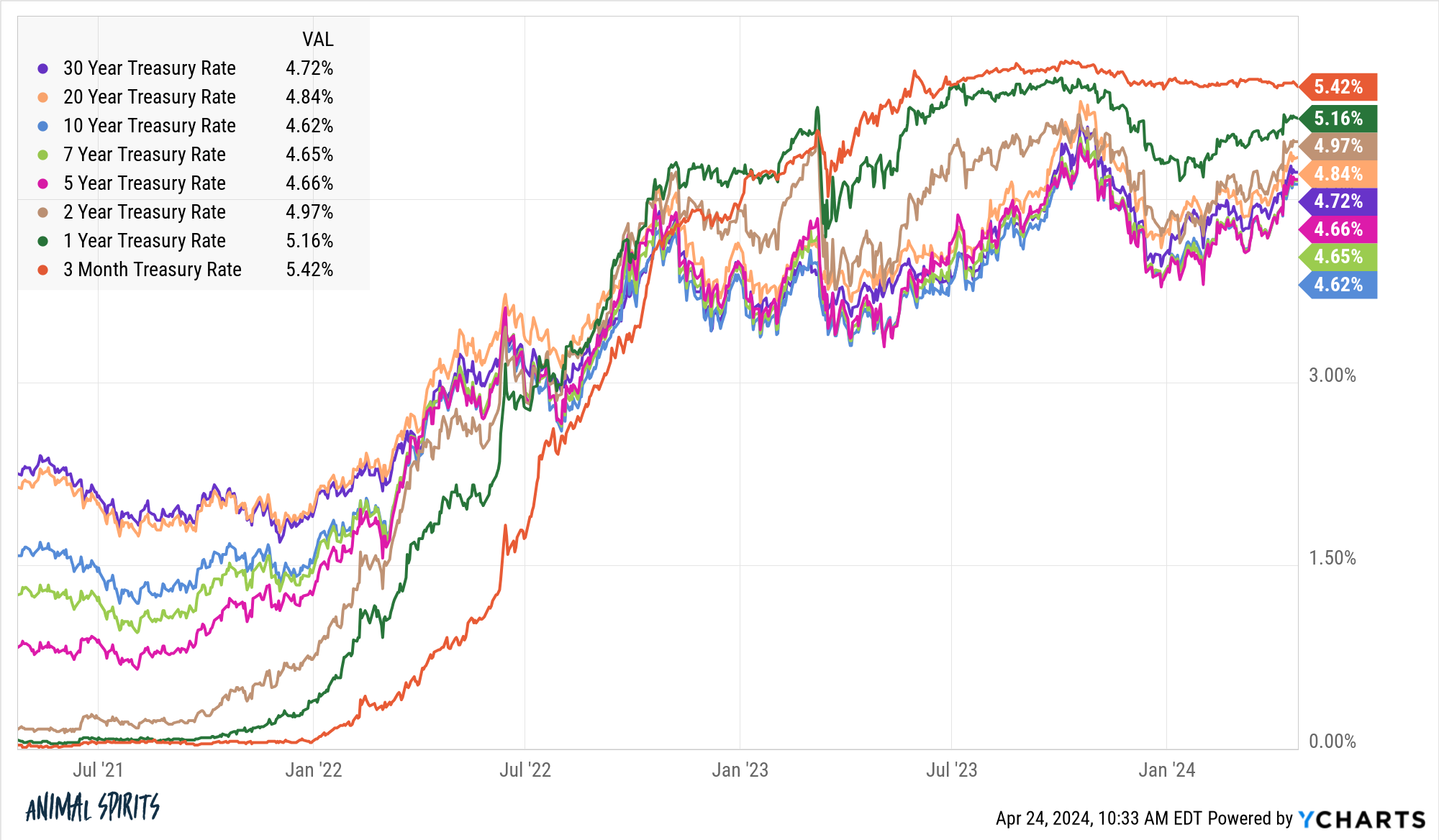

After rising at a fast clip last fall, interest rates dipped but they are now going back up again:

The spread between the short and long ends of the curve is compressing.

This should be bad for the stock market, right?

Yes, in theory, but the historical track record suggests rising interest rates are not the end of the world for the stock market.

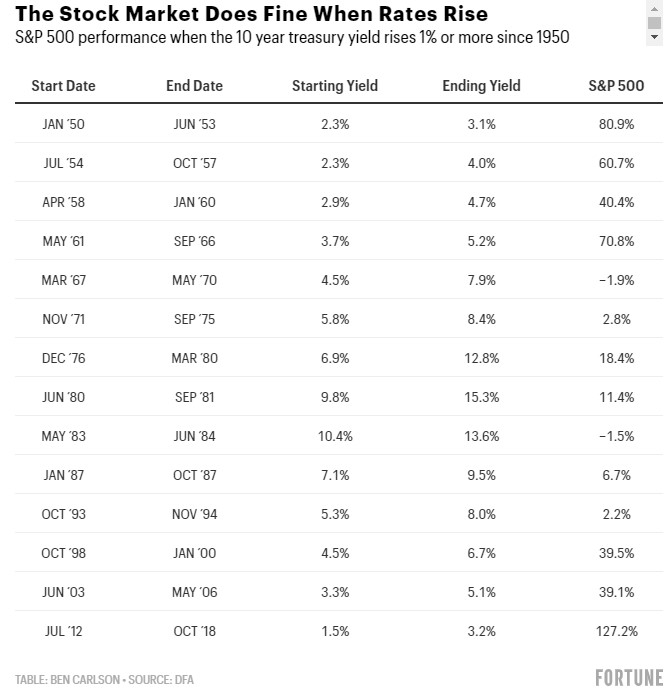

In fact, the S&P 500 has done just fine during rising interest rate cycles in the past. I’ve written about the stock market vs. rising rates in the past:

From 1950 through the pre-pandemic era, the average annualized return when the 10 year yield jumped 1% or more, was just shy of 11%. That’s basically the long-term average performance for the U.S. stock market. It was only down twice when this happened and the losses were minimal.

That’s rising rates but how does the actual level of rates impact future stock market returns? Surely, investing when rates are higher should lead to lower returns, right?

The relationship between interest rates and stock market performance is murky at best.

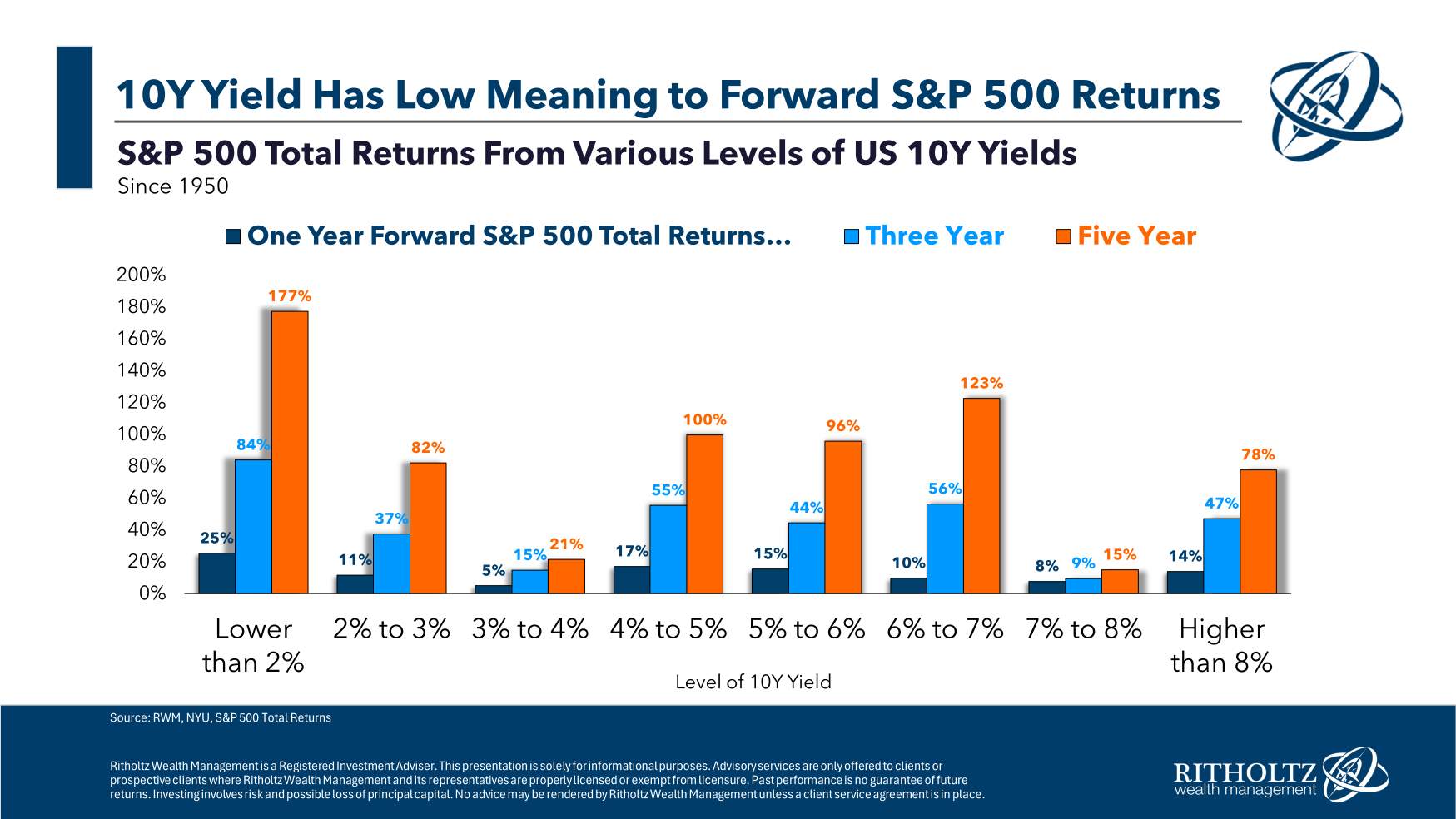

Going back to 1950, I broke down the forward 1, 3, and 5 year average returns from various interest rate levels:

It’s certainly not a one-to-one correlation where higher rates lead to lower returns. The lowest returns have come in the 3-4% and 7-8% ranges. The best returns have come when rates are 2% or less, which makes sense when you consider rates were only that low during two of the biggest crises this century (the GFC and Covid).1

Look at the 4% to 6% range, which is where we are now. The returns have been pretty good. Maybe one of the reasons for this is because the average 10 year yield since 1950 is 5.4% (the median is 4.7%). Rates like this occur during normal times (if such a thing exists).

There’s really no rhyme or reason to the relationship between interest rate levels and forward stock market returns.

You could slice and dice this data in a million different ways (rates rising/falling, inflation rising/falling, growth rising/falling, etc.), but the most important question is this: Why are rates higher in the first place?

In the 1970s, higher rates were a headwind to stocks because inflation was out of control and the economy was experiencing stagflation.

The biggest upside surprise to the economy in this cycle is rates are higher for longer because economic growth is higher for longer. The Fed hasn’t had to cut interest rates yet because the economy remains relatively strong. Rates have been higher for a while now yet economic growth accelerated at the end of 2023.

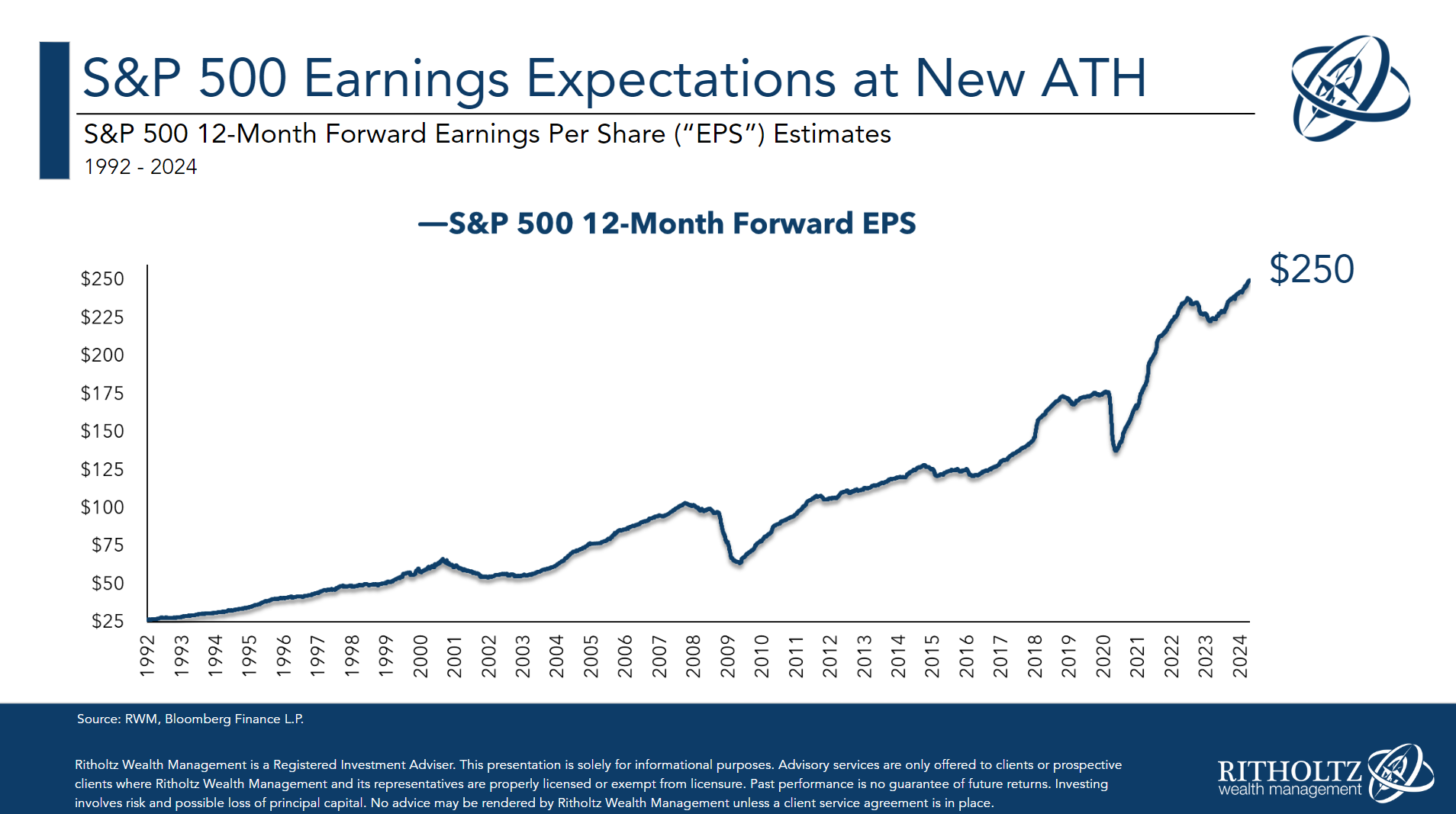

When you combine higher economic growth with inflation and pricing power by corporations, guess what you get?

Higher earnings!

The stock market likes higher earnings.

Higher rates with higher economic growth are better for the stock market than lower rates with lower economic growth. If rates fall significantly from current levels, that’s probably a bad sign if it’s occurring because of an economic slowdown.

It doesn’t always work out like this and I don’t know how long the current situation will last.

The point here is that you can’t simply examine any variable in isolation. Economic and market data require context.

We spoke about this question on the latest edition of Ask the Compound:

Bill Artzerounian joined me again this week to tackle questions about automating your finances, the tax implications of a company sale, how to offset RWM taxes and the pros and cons of a Roth 401k.

Further Reading:

Inflation Matters More For the Stock Market Than Interest Rates

1It’s also worth pointing out that interest rates under 2% have been rare historically. Rates have been at those levels less than 7% of the time since 1950.