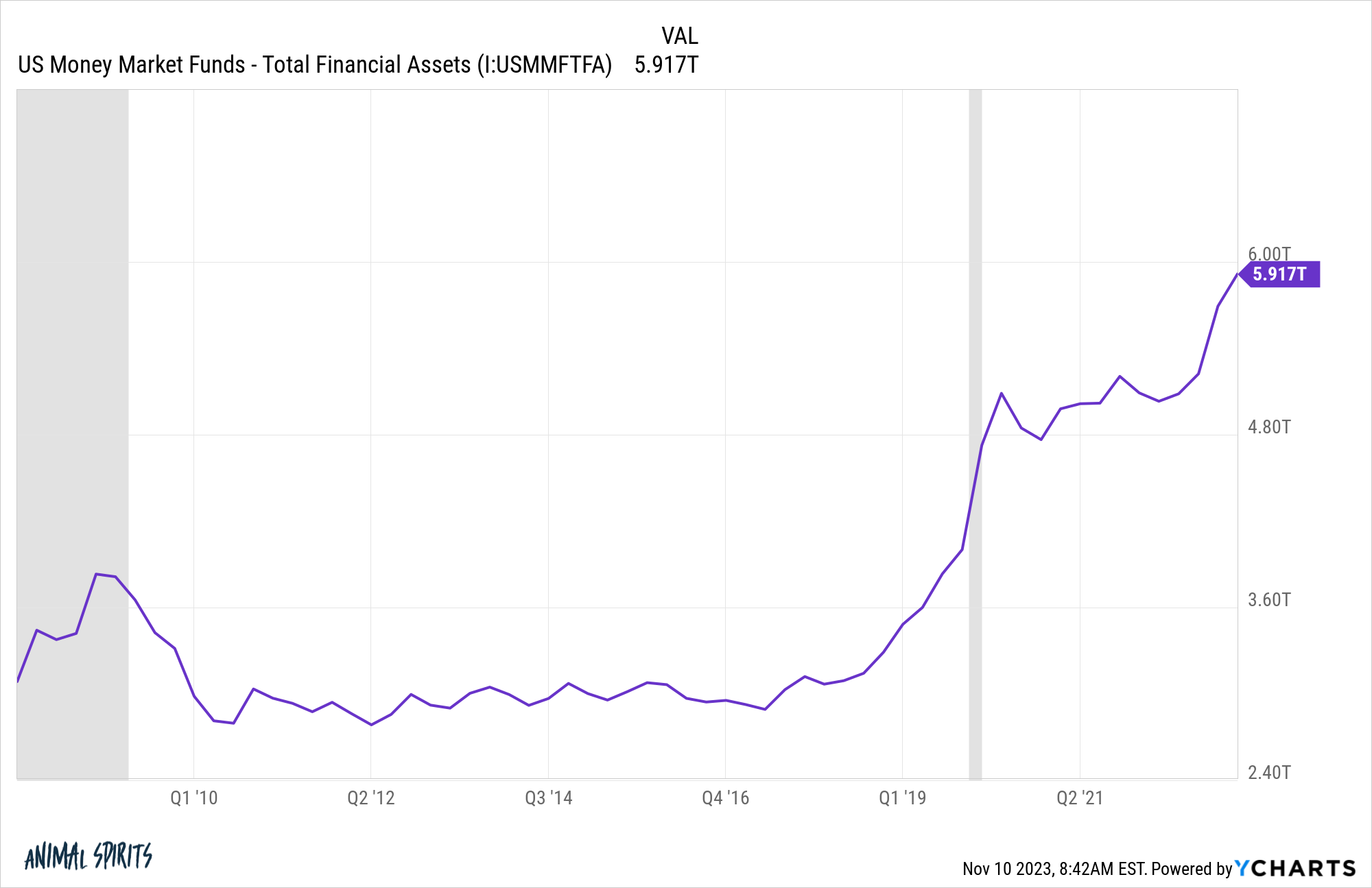

Boring old money market funds are the hottest thing in fund flows this year. Just look at the massive amount of money that has poured into these things:

There’s a good reason these funds saw stagnating asset growth in the 2010s — there was no yield. Now there is.

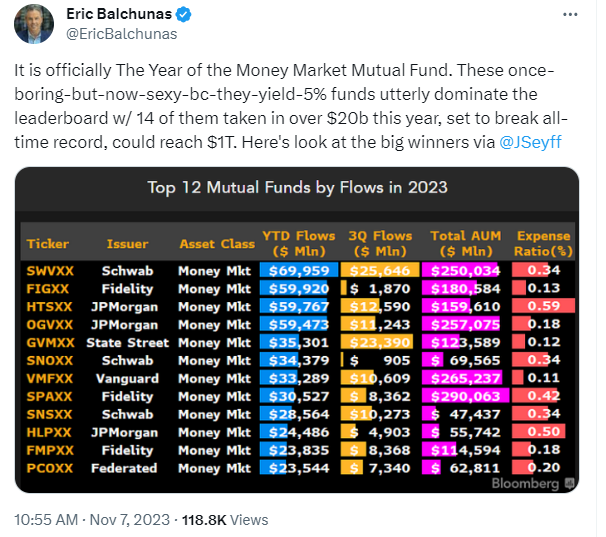

Bloomberg’s Eric Balchunas and Jeff Seyffart show how banks and fund companies across the board are vacuuming up money now that money market funds are yielding north of 5%:

Investors have a history of chasing the best-performing funds but they also have a history of chasing yield in money market funds.

Money market funds are still a relatively new development in the fund world.

Back in the Great Depression the government imposed a limit on the amount of interest a bank could pay to depositors because so many banks failed in the 1930s. The ceiling was a little more than 5% which didn’t matter for many decades because rates never got that high.

Then the 1970s happened. Inflation caused higher interest rates and banking customers couldn’t earn the much higher yields now available in short-term credit instruments.

A guy by the name of Bruce Bent recognized what was going on here and didn’t like it. So in the early-1970s Bent created the first money market fund, which wasn’t technically a savings account so it could offer market interest rates and charge fees to get around the regulations.

Bent had a powerfully simple idea that made sense and had wonderful timing — the perfect combination for fund flows.

The 1970s were an awful decade for stocks and bonds alike. Cash-like investments outperformed both of the two main asset classes because interest rates moved up so quickly.

Joe Nocera wrote an article in Esquire describing the sea change that came about from money market funds titled The Ga-Ga Years:

On January 7, 1973–more than a year after the SEC gave its approval–Bent got a big break. A New York Times reporter, after months of badgering, wrote a short article about the fund. “The next day we got a hundred phone calls,” says Bent. “By the end of the year we had $100 million in assets. People I knew on Wall Street would send their mothers to me. Little old ladies would say to me, ‘My son told me you have a good thing.’ Then they’d say, ‘I’m nervous and I don’t want to lose my money.'”

Then Fidelity’s Ned Johnson figured out how to add check-writing capabilities, giving even more ammo to the bankers, brokers and salespeople. It was a fund with both investing and saving attributes in a decade when people were in search of safety.

Nocera called money market funds the seminal invention in the money revolution, at least on the investment side:

It was the first truly different wrinkle in personal finance since the credit card. It was the first product to cross previously iron-clad boundaries between banks and other financial institutions, not to mention the psychological (but no less ironclad) boundaries separating “savings” money and “investment” money in the minds of most Americans. When the financial habits of the middle class began to change, of necessity, toward the end of the decade, the money market fund was the product that made such changes feasible, and even thinkable. Its creation signaled the beginning of the end for the old world of personal finance.

By 1981, T-bills were yielding around 16% with the long bond in the 14-15% range. But bonds were getting dinged every year from rising rates. Money market funds were yielding closer to 17-18% and you didn’t have to worry about interest rate risk.

In an age of inflation, Wall Street quickly learned that yield sells.

The money market fund quite changed the course of the fund industry forever.

John Bogle described how this new fund kept Vanguard afloat during the late-1970s and early-1980s in his book Stay the Course:

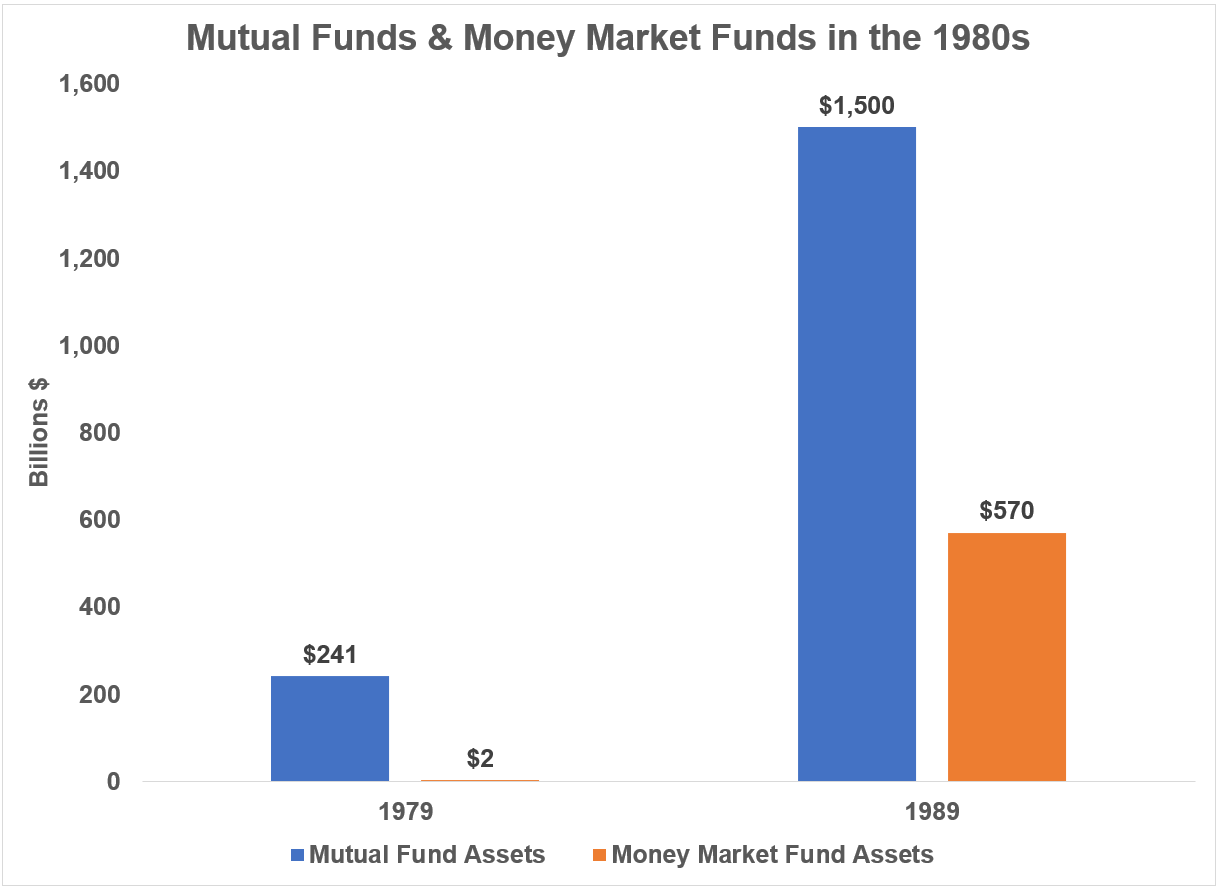

Throughout the decade of the 1980s, I often bragged to our crew about Vanguard’s spectacular asset growth, in part to maintain and build on the solid morale we had established. But in reality, our growth largely reflected the growth of the burgeoning fund industry. During that decade, mutual fund assets leaped from $241 billion to $1.45 trillion. The charge was led by money market funds, which soared from $2 billion to $570 billion, accounting for almost half of the increase.

Here’s what Bogle wrote in chart form:

From 1974-1981, the share of assets in stocks and balanced funds at Vanguard fell from 98% to 57%. The share of assets in money market funds went from 0% to 35% (bonds made up the difference).

Money market fund assets leapt from $4 billion in 1977 to $185 billion in 1981. Bogle admitted, “With their high interest rates and relatively low risk, money market funds created a new and fast-growing asset base that may have, in fact, saved the mutual fund industry.”

When the economic and market malaise of the 1970s had finally passed, those assets were already in the system to act as a buyer of stocks in the ensuing bull market that began in the 1980s. Ten million households owned money market funds by the early-1980s. When the tax-deferred individual retirement account hit the scene, many of those money market investors opened accounts and bought stocks.

Which brings us back to the present.

Financial pundits like to say, “I’ve seen this movie before and I know how it ends.”

We have seen this movie before but I don’t know how it ends.

My biggest question from the firehose of money flowing into money market funds is this: How much of that money will act as cash on the sidelines if and when money market yields fall?

There is a case to be made that this money will chase risk assets higher during the next bull market. Or this money could stay in relatively safe assets if it came from baby boomers de-risking their portfolios as they enter or approach retirement.

It could depend on the path of interest rates from here which is the ultimate unknown in this equation. If the past cycle has taught us anything, predicting interest rates is more or less impossible.

If yields stay high, the money will likely keep flowing into fixed income funds like money markets.

If yields go back down, it will be interesting to see how investors will react now that we have so many retired baby boomers and more on the way in the coming years.

If history has taught us anything, something else will come along to grab investor attention and fund flows.

Michael and I talked about money markets, inflation and much more on this week’s Animal Spirits video:

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

Further reading:

How Individual Retirement Accounts Changed the Stock Market Forever

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- How social media shapes economic perception (Kyla’s Newsletter)

- We need to talk about your retirement spending (Morningstar)

- 10 things I know about food people don’t want to believe (Washington Post)

- It never gets easier (Dollars & Data)

Books: