I’m generally not a fan of completely rethinking your asset allocation just because you wish you would have invested in something else with the benefit of hindsight.

Fighting the last war can be a damaging strategy if you’re constantly investing in the rearview mirror based strictly on performance.

The proliferation of black swan strategies following the 2008 crash comes to mind.

But there’s nothing wrong with being thoughtful about your asset allocation if you do so with your eyes wide open to the trade-offs and risks involved.

The bond bear market has caused a number of fixed income investors to recalibrate their range of outcomes when it comes to the bond side of the portfolio.

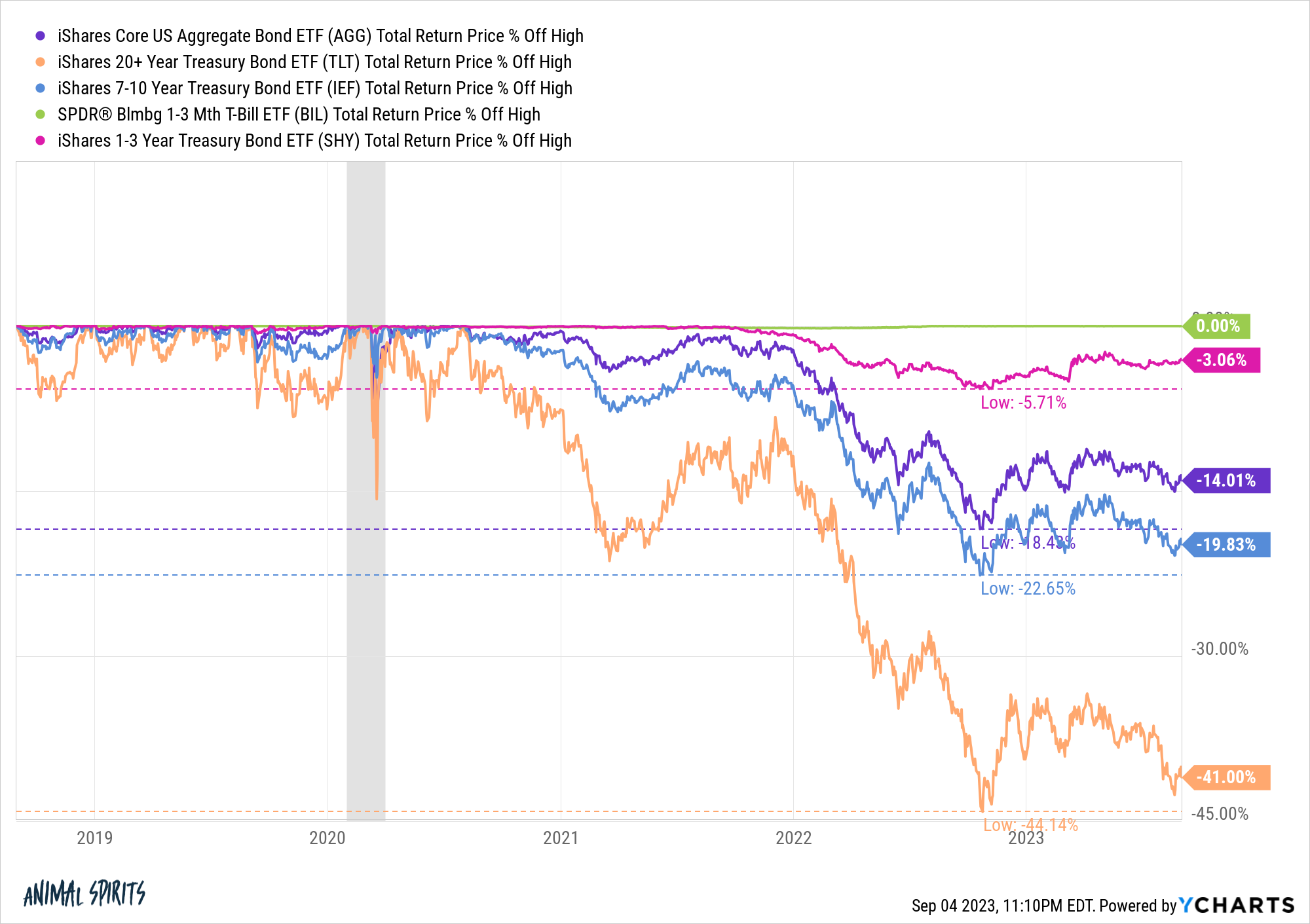

Just look at the drawdowns in a number of different fixed income ETFs these past few years:

Long-term bonds have gotten smoked.

That shouldn’t come as a huge shock since these are long duration assets. Volatility comes with the territory when we’re talking 20+ year securities.

But I’m not sure many investors were expected drawdowns of 20% in total bond index funds (AGG) or intermediate-term bonds (IEF).

The historical yield premium for longer duration bonds doesn’t seem quite so appealing when you see 1-3 Treasuries (SHY) get hit with a mere flesh wound and 1-3 month T-bills (BIL) not fall in the slightest.

The fact that ultras short duration fixed income is a better hedge against inflation, exhibits lower volatility and has much lower drawdown risk than longer duration bonds has many investors wondering if they should consider a change to the bond side of their portfolio.

What if you just went to short-term cash instruments instead of bonds?

There are trade-offs in the various bond durations just like every other financial asset when it comes to potential risk and reward so I like to look at these decisions through the lens of asset allocation.

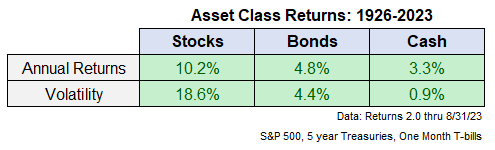

These are the long-run returns going back to 1926 for stocks (S&P 500), bonds (5 year Treasuries) and cash (one month T-bills):

Stocks have higher historical returns and volatility than bonds which have higher historical returns and volatility than cash.

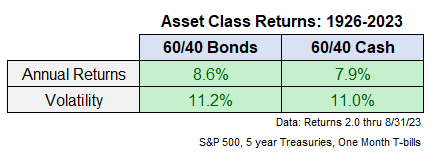

To better understand the trade-offs in going from bonds to cash, I looked at two 60/40 portfolios — one with the 40 in 5 year Treasuries and one with the 40 in one month T-bills, with an annual rebalance.

These are the historical results:

This is what you would expect — slightly lower annual returns and slightly lower volatility for a portfolio with cash than bonds.

These returns make sense from the perspective of risk and reward, which are always and forever attached at the hip.

But the results are still close enough to make you think.

Of course, these are annual returns for a period of almost 100 years. It can also be instructive to look at shorter time frames to gauge the differences here.

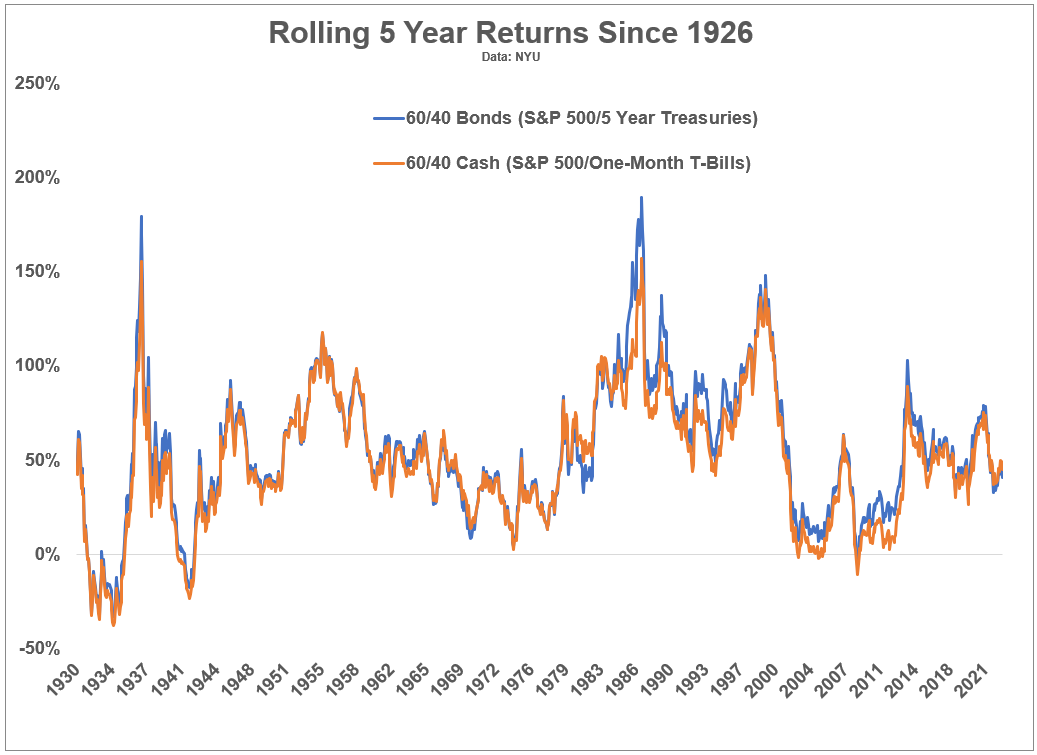

These are the rolling 5 year total returns for each of these 60/40 portfolios:

The bond returns have been higher most of the time but it’s not a huge difference.

Investors shouldn’t expect to see the same levels of drawdowns in bonds going forward. Unless bond yields head south of 1% again and then quickly go back to 5% in short order, the current bond bear market is likely to be a historical outlier.

Higher starting yields in intermediate-term bonds makes them a lot more attractive than they were a few years ago.

The good news for investors is you don’t have to pick one or the other.

If we were to look at a portfolio of 60% stocks, 20% bonds and 20% cash, the annual return since 1926 was 8.3% with volatility of 11.1%, which is smack-dab in the middle of the two 60/40 portfolios we looked at in the table above.

You can utilize bonds to earn higher yields and protect against deflationary recessions.

And you can utilize T-bills and other types of cash equivalents (money market funds, CDs, high yield savings accounts, etc.) to reduce downside volatility from rising rates and protect against higher inflation.

The bond bear market is a good reminder that diversification within asset classes can help weather the inevitable storms in the various economic and market cycles.

Diversification in all things helps you prepare for a wide range of outcomes without predicting what those outcomes will be in advance.

Further Reading:

Is 75/25 the New 60/40?