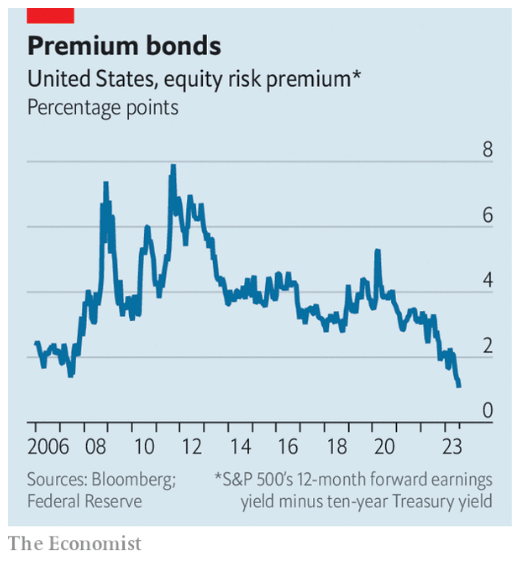

The Economist says by one measure stocks are the most expensive they’ve been in 5 decades:

This chart shows the equity risk premium which simply takes the forward earnings yield (the inverse of the price-to-earnings ratio) and subtracts the 10 year treasury yield.

I asked last week if valuations still matter anymore for the stock market but this one makes sense intuitively.

Interest rates are up a lot in the past couple of years. Stocks have had a nice run. On a relative basis, bonds are much more attractive now than they’ve been in a very long time.

So why is the stock market rising? Why are investors still allocating so much money to equities when the bond market is finally offering decent yields?

The simple answer is stocks are up and bonds are down.

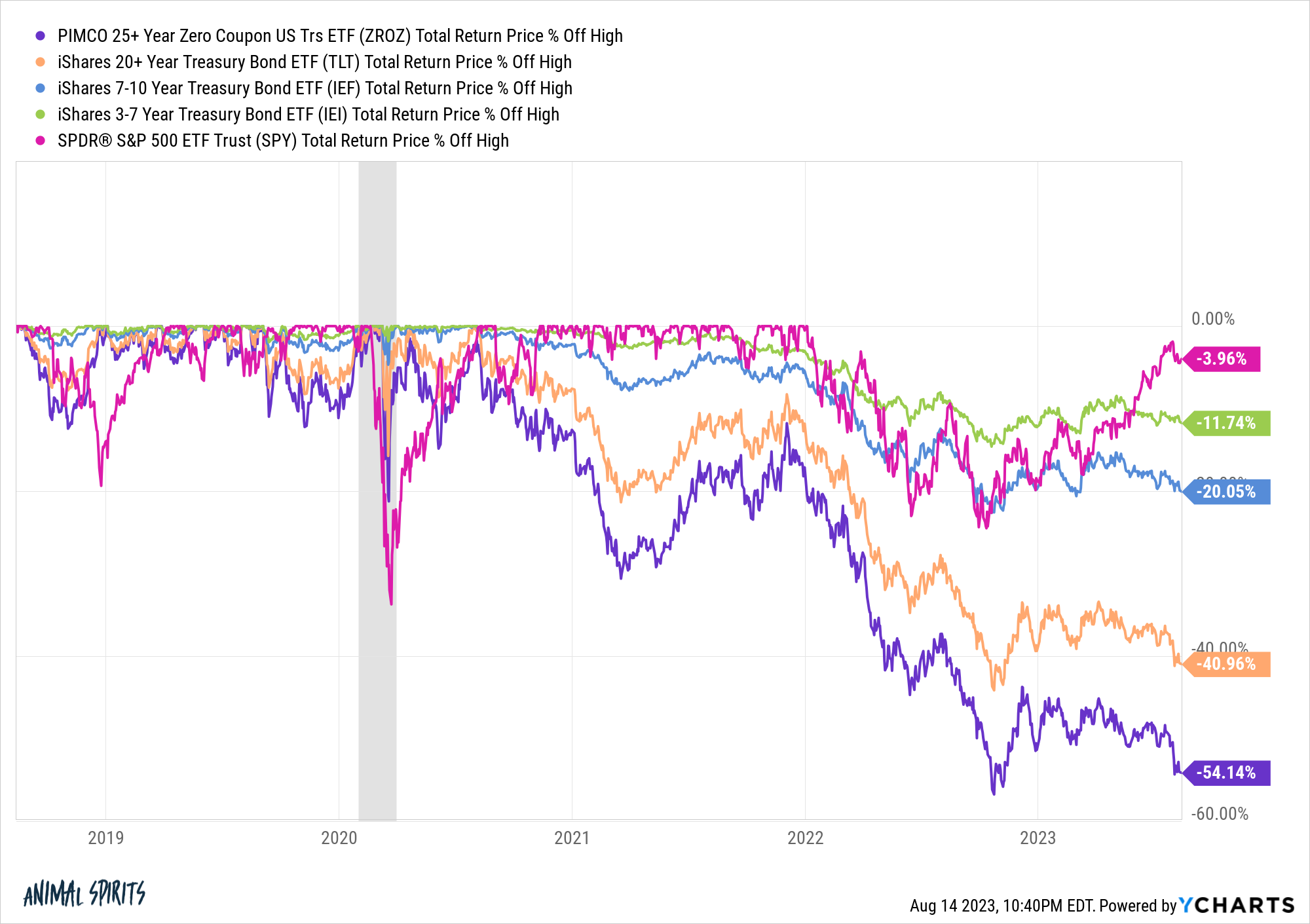

Here’s a look at drawdowns for various maturities in the bond market along with the S&P 500:

The S&P 500 has essentially round-tripped from the bear market.

Long-duration bonds are not only still down — they are squarely in market crash territory. Even 7-10 year treasuries are still in a bear market.

Investors are used to bear markets for stocks. We had one last year, in March 2020, in 2008, at the start of this century from the dot-com implosion, not to mention all of the corrections along the way.

Investors have become conditioned to buy, or at least hold stocks, after they have fallen. Not everyone has the ability to pull this off but history has taught stock market investors that stocks always come back. Buy when there is blood in the streets and so on.

But we’ve never seen anything like this in the bond market. While it’s true that higher yields should lead to higher expected returns in fixed income, there is a psychological toll from these losses.

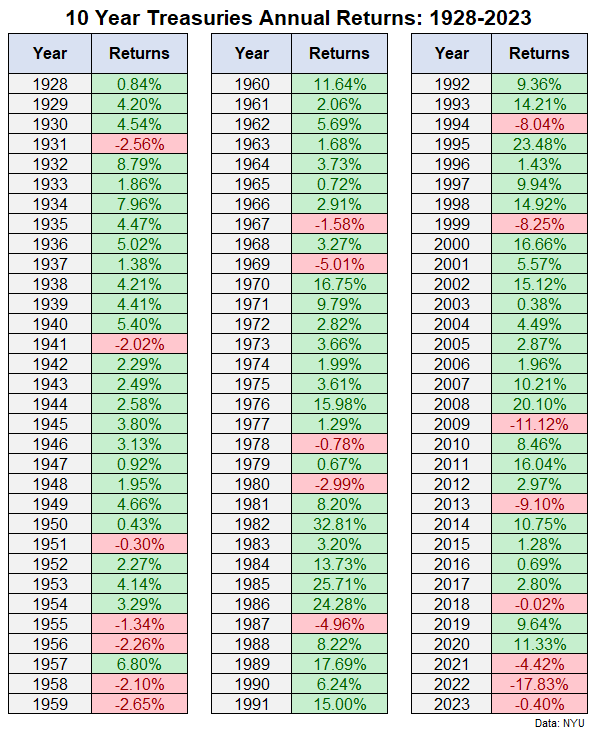

If interest rates keep rising we could be looking at an unprecedented run of losses in the bond market:

Obviously, 2023 is not over yet but we’re looking at the possibility of three years in a row of losses in the benchmark U.S. government bond.

There was a stretch in the 1950s with 4 losses in 5 years but those losses were all less than 3%. The cumulative return from 1955-1959 was -1.8%, hardly a reason for alarm.

Other than that, there hasn’t been another instance of back-t0-back losses for 10 year treasuries until the past two years.

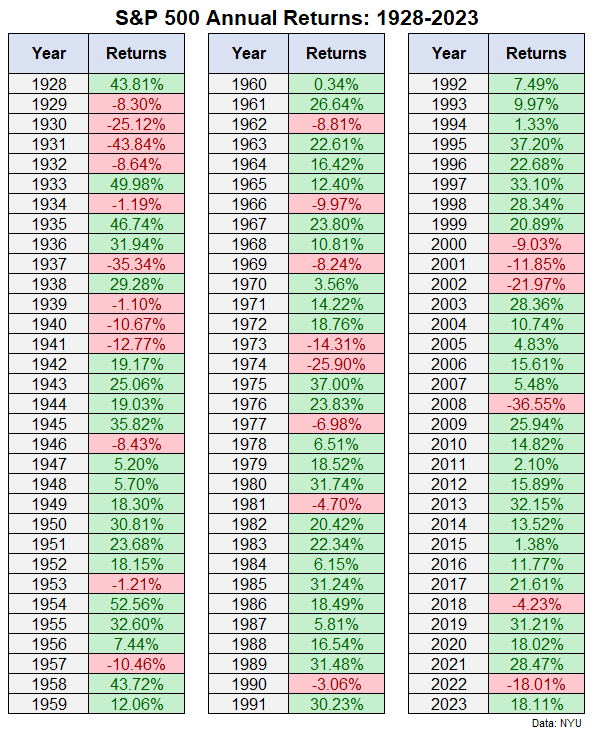

Three down years in a row doesn’t even happen in the stock market all that often:

The U.S. stock market fell four years in a row from 1929-1932. It was also down three years in a row from 1939-1941. The most recent back-to-back-to-back losses were from 2000-2002.

If rates keep rising things are going to get worse for the bond market before they get better.

I don’t have the ability to predict where interest rates go from here. There is a good case to be made that rates could keep moving higher if the economic acceleration in growth continues.

The good news for bond investors in that situation is that expected returns keep right on rising with even higher yields. The bad news is you’re going to experience more losses in the meantime.

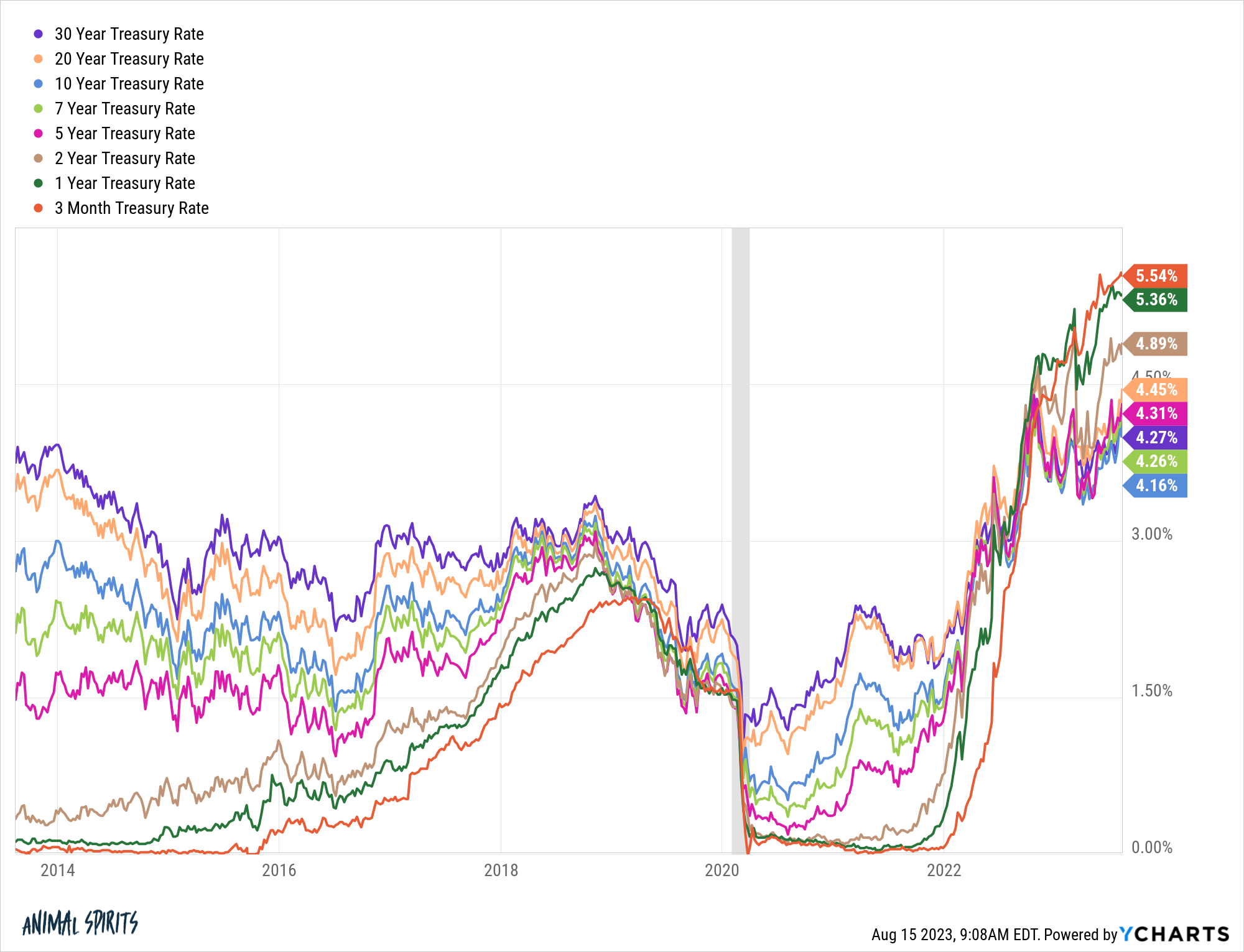

Bond yields across the board are at their highest levels in years:

This is a good thing for those looking for regular income and higher yields than the stock market.

But it might be difficult for investors to come around to the idea of moving a substantial piece of their portfolio from stocks to bonds when bond losses continue to pile up and the stock market is moving higher.1

In the tug-of-war between fundamentals and the pain of losing, it’s the pain that wins out most of the time in the markets.

Further Reading:

Market Timing & Interest Rates

1Maybe if the stock market rolls over yet again investors will change their tune.