In the fall of 1981 the yield on 30 year U.S. Treasury bonds hit 15%.

Fifteen percent! For 30 years!

One million dollars invested at that time would have been paying out $150,000 a year in interest for 3 decades.1 Can you imagine how much demand there would be for bonds yielding 15% for that long today?

The funny thing is when bond yields hit these levels in 1981 no one wanted to buy them.

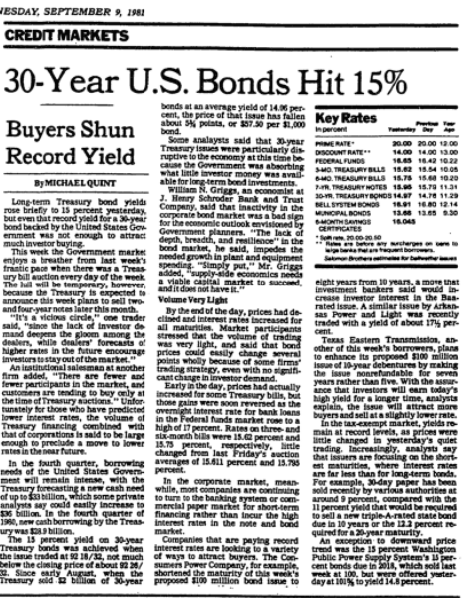

Here are some quotes from the New York Times when this happened:

Long-term Treasury bond yields rose briefly to 15 percent yesterday, but even that record yield for a 30-year bond backed by the United States Government was not enough to attract much investor buying.

”It’s a vicious circle,” one trader said, ”since the lack of investor demand deepens the gloom among the dealers, while dealers’ forecasts of higher rates in the future encourage investors to stay out of the market.”

That was the bond buying opportunity of a lifetime. Those are the kinds of yields where you can go to the beach and live off the interest…and no one wanted them.

The problem with playing Monday morning quarterback with something like this is the investments that look like generational buying opportunities with the benefit of hindsight often seem like the riskiest bets in the moment.

There were many reasons to shun bonds in the early-1980s. Inflation was so high that real returns weren’t nearly as juicy as those abnormally high nominal yields.

No one knew at the time that rates and inflation were peaking and about to fall for four decades. Investors were dealing with nearly two decades of rapidly rising rates and prices.

Plus, bonds were a dreadful investment for some time by that point.

From 1946-1980, long-term government bonds lost an astonishing 60% of their value after accounting for inflation.2

It’s no wonder investors were treating bonds like they were nuclear waste.

Investors assumed inflation would stick around forever.3

One would assume investors would all want to own bonds and shun riskier investments when yields are so high but that’s not always the case.

The 1987 Black Monday crash is a perfect example.

The reasons for that crash are still a little murky to this day but one of the reasons for the stock sell-off was a swift rise in interest rates:

There was a lot more to it than that but interest rates going from 7% to start the year to more than 10% right before the crash certainly had a bearing on the risk appetite of investors.

The question is: Why didn’t all investors simply move their portfolio to government bonds that were yielding 10%?

You could have locked up your capital for 10 years in high-quality, default-free bonds yielding double-digits instead of watching your money crash more than 20% in a single day in the stock market.

It’s probably because the S&P 500 was up more than 40% in 1987 before that fateful day in October. Not to mention the fact that the S&P 500 was up more than 17% per year in the 8 years leading up to 1987 before that 40%+ gain occurred.

In that context, even 10% per year guaranteed from the U.S. government doesn’t sound all that appealing.

Which brings us to today.

The bond yields of 2023 are minuscule compared to the 10-15% you could earn in the 1980s at times. But the nearly 5% you can now earn in Treasury bills that mature in less than a year’s time looks pretty darn good compared to the yields of the past 10-15 years.

Many market prognosticators are beginning to wonder if going from a world of 0% rates to a world with 5% yields will cause a massive shift in investor allocations from stocks to bonds.

It would surprise me if there weren’t a ton of investors who took advantage of this situation, especially retirees and those with short-to-intermediate-term saving needs.

For years the low interest rate environment was pushing people further and further out on the risk curve to earn anything approaching a respectable yield. For the first time in a long time, you can earn that respectable yield on relatively safe, short-term government bonds.

This is a good thing for savers.

But I’m not so sure investors en masse are going to all of the sudden put their entire portfolio into T-bills.

We as a species like risk. We like to gamble and take chances.

That’s why we go to casinos and bet on sports and play the lottery and invest in options, crypto, start-ups, individual stocks and a whole bunch of other stuff that comes with the risk of loss.

The stock market was up 5% in the first two weeks of 2023. Most investors won’t be patient enough to wait to earn 5% over the course of an entire year.

Michael and I discussed how interest rates could change the allocation preferences of investors and much more on this week’s Animal Spirits video:

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

ANNOUNCEMENT — Future Proof registration is now live. This was hands down the best conference I’ve ever been to and we’re going to make the second iteration even better. Register here.

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- Financial planning when you’re young involves a lot of guessing (Oblivious Investor)

- The fear of investing is a familiar and costly story (Monevator)

- How much money do you need to make to be rich? (Dollars & Data)

- Trophies (Casey’s Notes)

- Your investment portfolio has nothing to do with who you are (Klement on Investing)

- How much Netflix can the world absorb? (New Yorker)

1Right now you can get roughly $36,000 a year in interest for a $1 million investment in long-dated U.S. government bonds.

2The nominal returns were actually okay in this environment at around 2% per year. It’s just that inflation was running at nearly 4.5% during this time so real returns were underwater.

3The 30 year return for the S&P 500 from 1981-2010 was 10.6% per year. So owning that long-term bond in 1981 outperformed the stock market by a wide margin. I’m cherry-picking here but it’s still pretty wild.