One of the strange things about growing older is you begin to realize how much your place in life determines your taste in entertainment.

There are movies and TV shows that stand the test of time but there are also many that hold a special place in your heart simply because you watched them at a certain age.

There are movies that I loved as a little kid that I probably wouldn’t relate to as much today. Same thing as some of my favorites when I was in high school and college.

Now that I’ve hit middle age and have a family of my own there are certain movies or shows that hit differently.

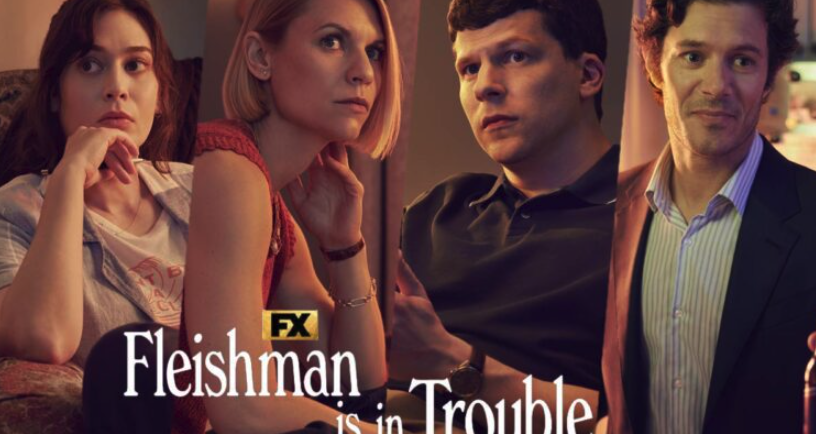

Fleishman is in Trouble (on Hulu) is this kind of show.1

It checked all the boxes for middle-aged angst — career, kids, old college friends, nostalgia for your youth, life in the suburbs, keeping up with the Joneses and of course, money.

The money stuff played a big role in the plot because the show takes place in New York City.

Jesse Eisenberg plays Toby Fleishman in the show. Fleishman is a doctor who is relatively rich by the standards of the rest of the world. But he didn’t feel rich considering he lives in Manhattan.

When fighting with his wife Rachel (played brilliantly by Clare Danes), Fleishman complains:

Excuse me, I make almost $300,000 a year. I am a rich man in every single culture except the 40 stupid square blocks that you insist we live within.

His old college friend Libby, our voiceover guide to the show, admitted he made a very decent amount of money by American standards but not Hamptons money.

I imagine it’s very easy to feel relatively poor in New York City no matter how much or how little you make considering the city is home to some of the wealthiest people on the planet.

The New York Times recently took to the streets of NYC to ask random strangers how much money they make. The median household income in New York City in 2021 was just over $70k which is pretty much the same as the rest of the country. The numbers they got were all over the map.

This is what a costume designer told them:

I made a lot of money on unemployment during Covid. And now I’m back to $27,000 a year. I wish I wouldn’t struggle so much. I wish I would get paid more for my value.

This was a finance guy:

A stockbroker dressed in a plaid suit with a floral pocket square was happy to talk … at first. He eagerly told us that he made $300,000 a year. But as we continued to speak, he became embarrassed that he didn’t make more. In the end, he withdrew his quotes.

When it comes to income it’s not how much you make that determines your feelings towards money; it’s how much you make relative to those around you.

Hundreds of students and faculty at Harvard were once asked to choose one of the following:

A: Your current yearly income is $50,000; others earn $25,000.

B: Your current yearly income is $100,000; others earn $200,000. (purchasing power is the same in each choice).

Half of the respondents choose A, which is lower than you could make on an absolute basis in the second choice but relatively higher than what others would make in that scenario.

Maybe this just means Harvard grads should move to the midwest or south rather than the coasts to enjoy a lower cost of living but this isn’t as crazy as it may sound at first blush.

We humans tend to care a lot more about better or worse rather than good or bad when it comes to our finances.

The problem with using a high income as a signal of success or failure in life is it often comes with consequences. This is especially true once kids enter the picture.

In the 1960s, less than 30% of all married households were dual-income families. That number has now more than doubled to more like 60%.

There are reasons for this change. Having children is more expensive than it used to be. The cost of education is higher. The cost of childcare is higher. The cost of housing is higher. The cost of transportation is higher.

A Pew Research study shows that dual-income households with at least one child under the age of 18 living at home make double the income of households with children where only one parent works.2

That extra income comes at a cost to some families though. Dual-income families reported being much more pressed for time and felt like they didn’t get to spend as much time with the kids as they would like.

There are no easy answers here.

Most decisions in life are about trade-offs.

You could focus all of your attention on work but other areas of your life are likely to suffer.

You could live in one of the biggest cities in the world but you’re likely going to have to pay up for that privilege.

You could prioritize family time but it could cost you in the form of lost income or career advancements.

Fleishman’s college friend Libby was having a difficult time letting go of her youth and transitioning into the middle age suburban mom phase of life. Her husband Adam explained:

“It’s not New Jersey,” Adam said. “It’s life. It’s being in your forties. We’re parents now. We’ve said all we needed to say.” I began to cry. He patted my head and said, “It’s okay, it’s okay. It’s the order of things. Now we focus on the kids. We mellow with age. It’s how it goes. It’s not our turn anymore.”

Focusing less on yourself and more on other people is a good way to frame the idea of trade-offs as you age.

Ryan Holiday calls this work, family, scene problem:

You can party it up and hang onto a relationship but you won’t have much time left for work. You can grind away at your craft, be the toast of the scene, but what will that leave for your family? Almost certainly it means they will be home, alone. If you’re as committed to the work as you are to a happy home, you can keep both but you will have no room for anything else—certainly late nights or hangovers or exotic trips. And if you try to have it all? Well, you won’t get any of it.

Holiday says you can only realistically pick two out of three when it comes to work, family or a vigorous social life. I tend to agree.

Based on where you are in life these choices could shift over time but it’s impossible to have it all.

No one has a perfect life. In fact, perfect is the enemy of good when it comes to both life and your finances.

Further Reading:

Don’t Try to Get Rich Twice

1I enjoyed the book too.

2For households where one parent works full-time and the other part-time, it was around 20% less than two full-time workers.