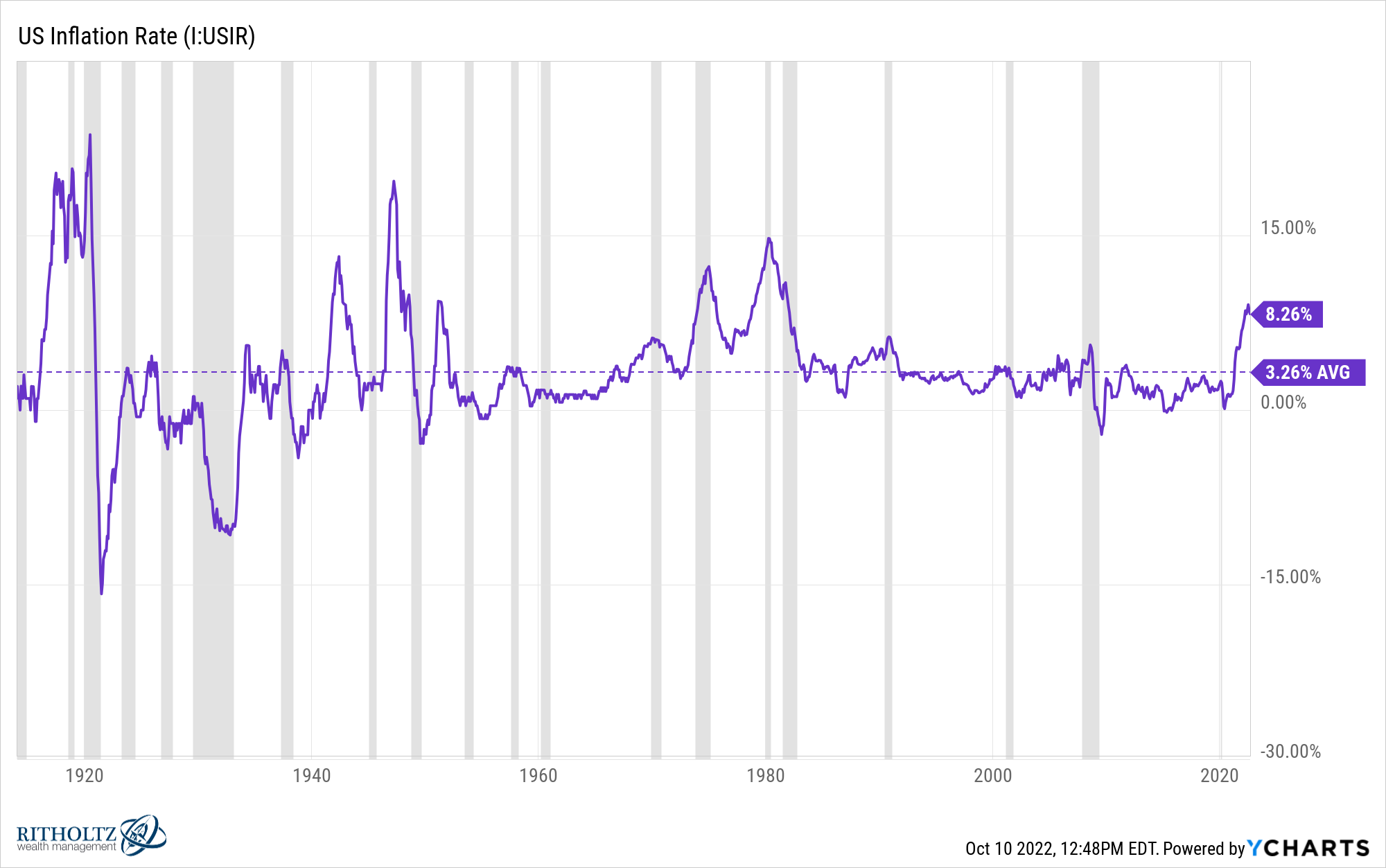

The long-term average inflation rate in the United States going back 100+ years is right around 3% per year.

Obviously, there is a range around that long-term average.

For instance, in the 38 years from 1983-2020, inflation finished the year below 3% more than 60% of the time. Inflation was running at more than 4% in just 5 years and finished above 5% just once (in 1990 when it was 5.4%).

Inflation has been mild for the past four decades or so to say the least (until the past 18 months or so that is).

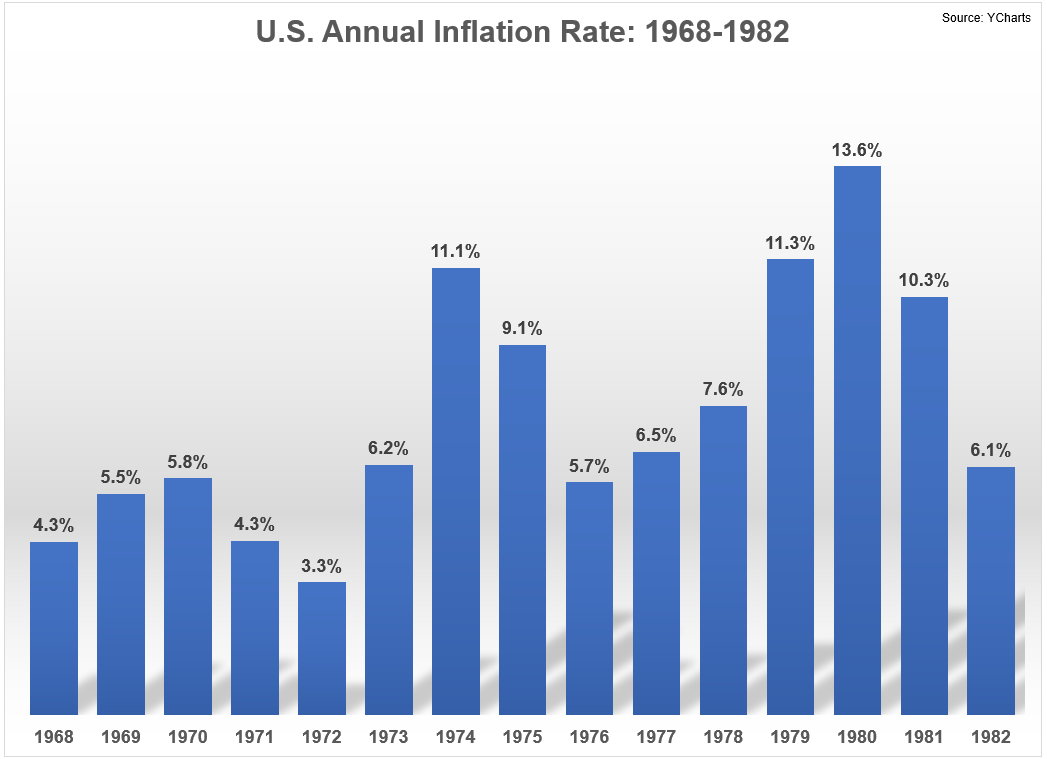

The period before this was much different.

From 1968-1982, the annual inflation was 4% or higher in 14 out of 15 years.1 Prices were up 5% or more in 12 of those years. It was more than 6% in 3 out of every 5 years and over 10% on four separate occasions.

For the current cycle, the inflation rate has been above 3% since April 2021, so we’ve been dealing with higher-than-average price increases for around 18 months.

Back then, inflation was above 3% for 18 years. While inflation did start coming down from the lofty levels of the early-1980s, it wasn’t below 3% in a calendar year until 1986.

So how did they finally tame the inflationary beast back then?

The Paul Volcker-led Federal Reserve put the economy into a recession…twice.

Volcker took over as Fed chair in the summer of 1979 and immediately began raising short-term interest rates. They would go as high as 20% before he was done.

There was a brief recession to kick off 1980 that was followed by yet another recession that started in 1981 just one year after the first one ended. From the start of 1980 through the end of 1982, the United States spent 22 out of 36 months in a recession. The unemployment rate was nearly 11% at the worst point of the cycle.

Like today, people really hated inflation back then.

But they didn’t like the recession any better.

Binyamin Appelbaum documented the Fed-induced recession in his book The Economists’ Hour:

The prime rate—the rate banks charged the best customers—topped out above 20 percent. Other rates went much higher. Consumers stopped buying cars and washing machines; millions of workers lost their jobs. Without jobs, many lost their homes and hopes of a comfortable retirement.

Factory workers suffered most. Unemployment in the auto industry reached 23 percent. Among steelworkers, it hit 29 percent. And the damage was enduring: a study of Pennsylvania workers who lost jobs in the mass layoffs found that six years later they were still earning 25 percent less than before the recession.

As Americans suffered, they noticed a new kind of pilot was guiding the economy. Auto dealers sent Volcker the keys to cars they could not sell. Home builders sent chunks of two-by-four wooden beams. “Dear Mr. Volcker,” one wrote on a block with a knothole. “I am beginning to feel as useless as this knothole. Where will our children live?” A home builders’ association in Kentucky published a wanted poster for Volcker. His crime: Murder of the American Dream.

Interest rates over 20%. Millions of people out of a job. Manufacturing and construction industries decimated.

Surprisingly, there was political will for this to happen. That’s how bad inflation was at the time.

Before he became president, Ronald Reagan told a reporter in the late-1970s, “Frankly, I’m afraid this country is just going to have to suffer two, three years of hard times to pay for the binge we’ve been on.”

Reagan gave his full support of the Fed’s actions that threw the country into a nasty recession.

And it worked…kind of. Volcker certainly slayed the dragon named inflation.

But I’m not sure you could say workers are much better off.

Applebaum explains:

In fact, American workers did not recover from the Volcker shock. The median income of a full-time male worker in 1978, adjusted for inflation, was $54,392. That number was not matched or exceeded at any point in the next four decades. As of 2017, the most recent available data, the median income of a full-time male worker was $52,146.79.

The nation’s annual economic output, adjusted for inflation, roughly tripled over those same four decades. Yet the median male worker made less money.

I have a hard time with these types of economic data points. While it may be true that inflation-adjusted wages haven’t grown based on certain measures, it’s not like everyone stays in the same income category their entire career.

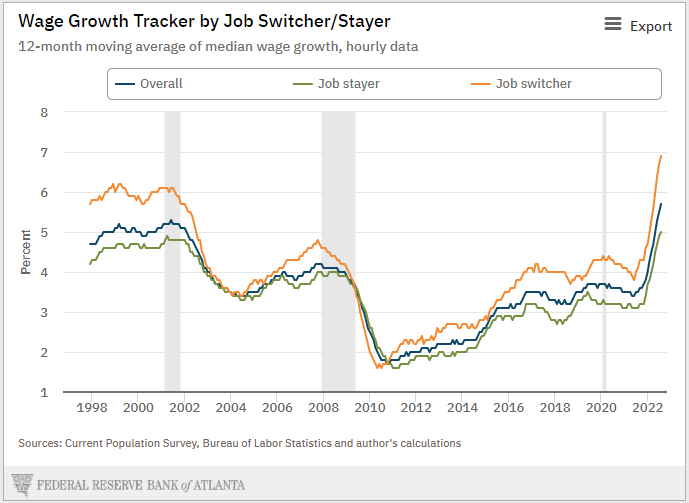

People move up (and sometimes down) the wage spectrum over time throughout their careers.

But labor (workers) has seen its negotiating power decline over the past four decades while capital (business owners) has flourished.

Now look at how much negotiating power workers have:

People who are switching jobs are seeing by far the biggest wage growth. This is a bad thing in that it can slow productivity (because of training and such) but a good thing in that workers finally have the upper hand for once.

Look, I understand that the Fed doesn’t want another 1970s on its hands. I can’t even imagine how angry people would be if we have another prolonged period of above-average inflation.

But there are a lot of differences between then and now.

The biggest one is probably the fact that workers had much more bargaining power back then because of the prevalence of unions. Fifty years ago roughly one-third of all U.S. workers belonged to a union that would represent them in contract negotiations for pay and benefits.

Today that number is more like 1 out of every 10 workers.

Other differences from this cycle include:

- Enormous fiscal stimulus because of the pandemic.

- Interest rates were too low.

- Supply chains were a huge problem.

- Consumers were spending too much money.

- The war in Ukraine.

This is not the 1970s in many ways.

I’m torn here because on the one hand the longer inflation sticks around the harder it can be to get rid of it. On the other hand, workers finally experienced a period in which they have some power over business owners.

Is that really such a bad thing if we see how that plays out?

Do we really need to give the upper hand back to capital just because labor finally saw some meaningful gains?

I’m just asking questions here.

Further Reading:

The Awful Economy Paul Volcker Inherited in 1979

1And the one time it wasn’t above 4% it still came in at more than 3%.