There are many conversations to be had in the midst of a bear market.

Is it time to buy?

Is it time to sell?

Is this the bottom?

Should I change my portfolio?

How much further do stocks have to fall?

How long do bear markets last?

What’s the best bet to outperform when the market does turn around?

One conversation I’ve had with a number of clients, friends, family members and even myself over these past few weeks is the following:

How do I invest a lump sum during a bear market?

People come into money for any number of reasons when it comes to a lump sum. It could be an inheritance, a bonus, the sale of an asset or a business or simply accumulated savings you’ve been sitting on for an opportune moment.

Captain Obvious knows this is a good problem to have but it’s a problem nonetheless because no one wants to screw up this decision. There’s a greater chance for regret when dealing with a larger amount than your usual contributions.

If you put the money to work all at once and the market falls even further you’ll be kicking yourself for not putting it to work slowly over time.

And if you spread your bets by averaging into the market but stocks rebound in a hurry, you’ll be kicking yourself for not putting it to work earlier.

Unfortunately, either decision will only be viewed positively or negatively with the benefit of hindsight. This investing thing would be much easier if we could all just predict the future.

Your two options here are to view this decision through the lens of regret minimization or historical probabilities.

My colleague and friend Nick Maggiulli1 has us covered in terms of historical probabilities. He wrote the definitive guide to dollar cost averaging vs. lump sum investing, research I share with clients and readers on a regular basis.

Here’s the main takeaway from Nick’s deep dive into the lump sum vs. dollar cost averaging:

When deciding between investing all your money now (lump sum) or over time (dollar cost averaging), it is almost always better to invest it now, even on a risk-adjusted basis.

This is true across asset classes, time periods, and nearly all valuation regimes.

Generally, the longer you wait to deploy your capital, the worst off you will be.

I say “generally” because the only time when you are better off by doing DCA is when averaging into a falling market.

Most of the time the market goes up. The stock market is up 3 out of every 4 years on average so putting your money to work right away, assuming you have the cash to invest, is your best bet, on average.

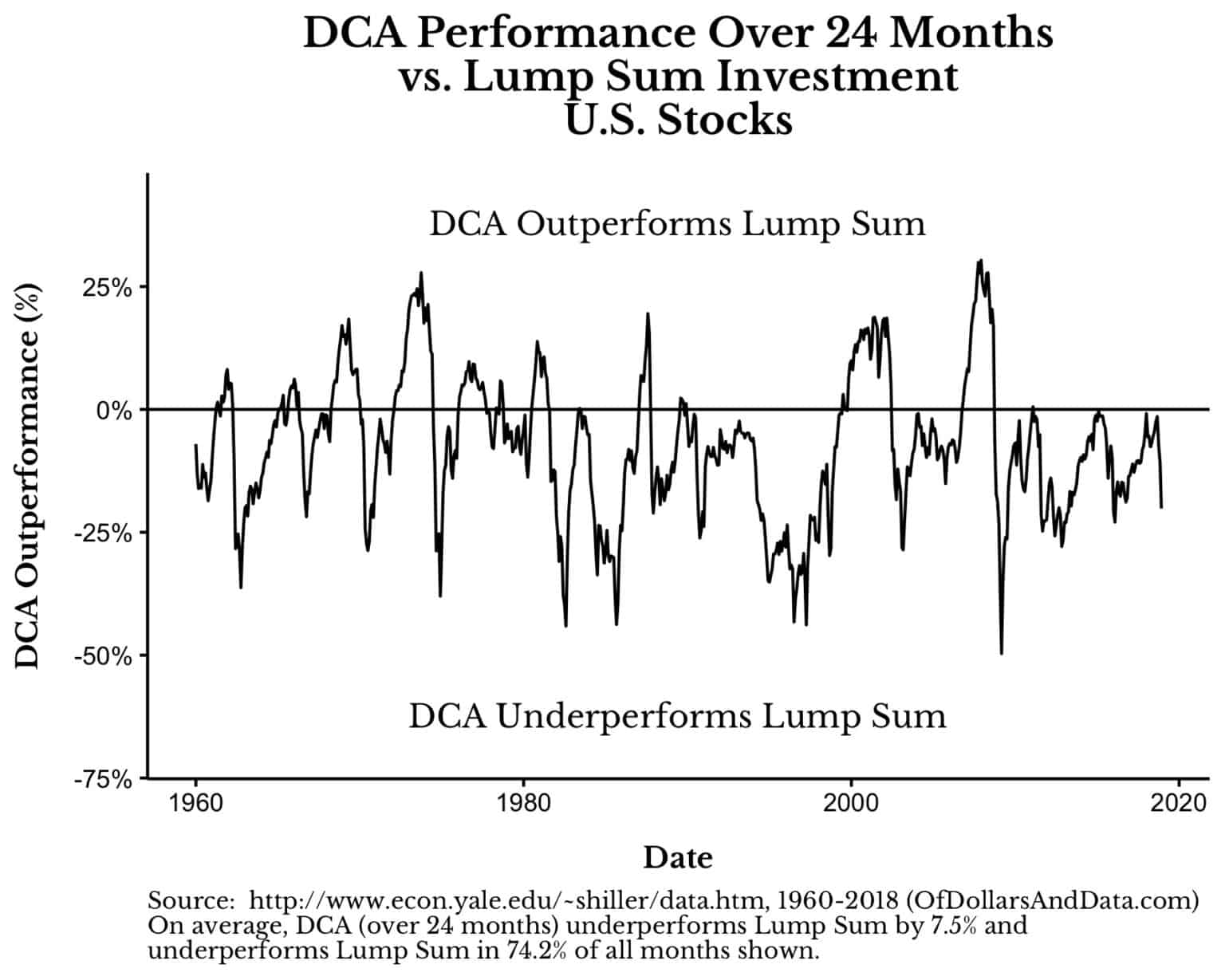

But Nick also found dollar cost averaging into a falling market is the one exception as you can see from this chart:

Nick notes the only times when dollar cost averaging tends to beat a lump sum is during a market crash scenario (think 1973-73, 2000-2002, 2007-2009, etc.).

This makes sense when you consider buying into a falling market allows you to average down while a lump sum could be made at an inopportune time before the crash.

But what if you’re already in a bear market?

What if the market has already crashed-ish?

The S&P 500 is currently down 19% from all-time highs. The Russell 2000 Index of small cap stocks is down 28%. The Nasdaq 100 is down 27%.

This is not an end-of-the-world situation but stocks are well off their highs.

Let’s say you’re lucky enough to find yourself in the position of having some extra cash to invest right now. How should you handle it?

You have a few options.

Option #1 is to simply invest the money immediately. A lump sum is clean and efficient and likely gives you the highest probability of a good outcome.

Option #2 is to dollar cost average a set amount of your cash over a specified interval. You could invest 20% of your money over the next 5 months or 50% over the next 2 months or 10% over the next 10 months or how ever you want to break things up.

Option #3 would be a hybrid approach where you invest a large chunk of your cash into the market now, say 50-60% and invest the remaining money over a preset interval.

You could get a little cuter with your rules by adding some market levels into the equation, say buying more if stocks fall an additional 10-20% or whatever but let’s keep this simple.

As luck would have it I found myself in a situation this past week where I had a lump sum to invest. Not life-changing money but more than my normal periodic contribution amounts.

My entire investing ethos is built around the idea of simplicity so I chose to invest the entire amount all at once.

I know the risks. Stocks could certainly have further to fall. It wouldn’t surprise me if they did. But the market is already much lower than it was just 6 months ago.

Why overthink it?

I’m comfortable with this risk because I can’t imagine I’m going to regret putting money to work with stocks down 20-30% in 2-3 decades when I actually need this money.

I didn’t want to second guess myself over and over again if I was sitting on that cash. I didn’t want this money hanging over my head.

You could read and fully comprehend Nick’s research on the subject and still decide to dollar cost average into the market because you’re more comfortable with that strategy.

It doesn’t really matter which strategy you choose as long as you stick with it come hell or high water.

It’s possible the stock market will make my decision to invest a lump sum look stupid in the coming weeks or months.

But my time horizon for this money is measured not in days, weeks or months but decades.

A long time horizon can be the great equalizer when making decisions like this.

Further Reading:

The Lump Sum vs. Dollar Cost Averaging Decision

1If you haven’t read Nick’s new book Just Keep Buying, it’s a must-read for topics like this. A great combination of investing and personal finance, two of my favorite subjects.