I have a theory about gas price movements that I cannot verify but believe to be true.

When oil prices fall, gas prices fall too but they do so on a lag and the decline isn’t as severe.

And when oil prices rise, gas prices rise immediately and the increase is commensurate or more.

It’s like a negative convexity or something.

It’s also possible this is all in my head because gas prices are the only ones advertised on huge signs everyone can plainly see driving down the road.

I was on Plain English with Derek Thompson a few months ago and he gave a great theory about the relative importance of gas prices:

It is kind of bizarre when you think about it this way.

There is a psychology to gas prices that you simply do not see with other goods or services.

The price of gas regularly comes up in conversation. It’s on the news all the time.

No one drives across town because bottled water is four cents cheaper per gallon but this is something at least a small percentage of the population has no problem doing when it comes to filling up their tank.

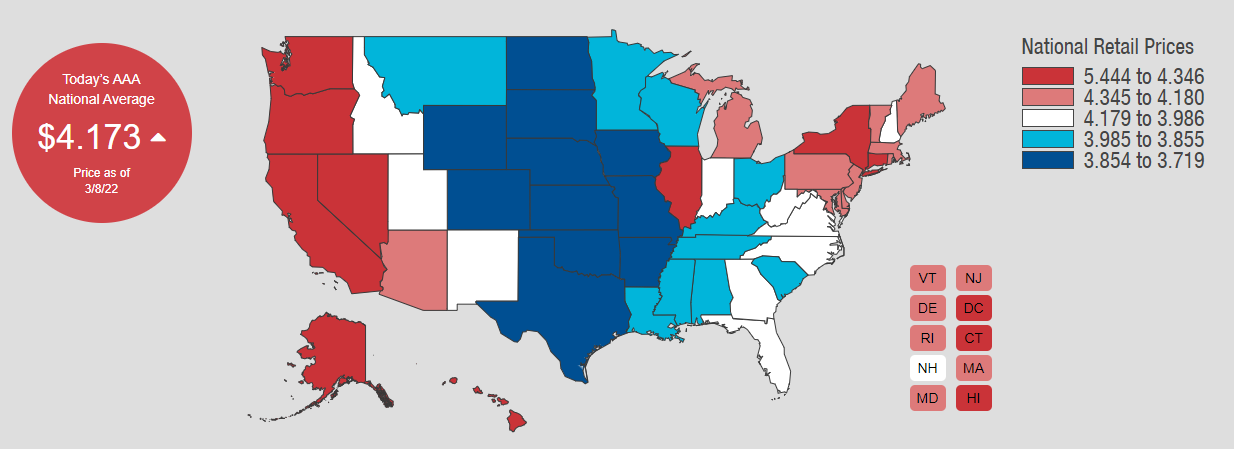

Average prices at the pump reached an all-time high yesterday according to AAA:

That’s up more than 50 cents a gallon since the end of February alone. We’ve now eclipsed the previous high of $4.16 a gallon that was reached when oil briefly hit $150/barrel in the summer of 2008.1

So while there is a psychological component when it comes to seeing these prices move very quickly in real-time, there is also a huge financial component to energy prices when it comes to household budgets.

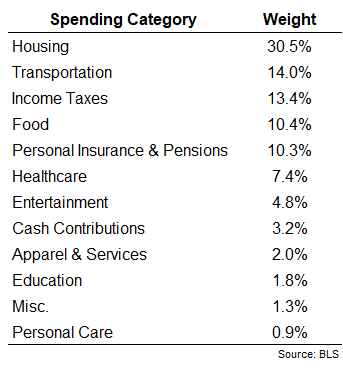

The Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes a report that looks at the consumption patterns of household budgets by breaking spending down into different categories.2

Housing and transportation are the biggest spending categories by far:

Gasoline itself isn’t a huge part of household budgets, coming in at around 2.2% of total spending. It is worth noting these spending levels are from 2020 (the last time this survey was taken) but even in 2019 and 2018 the numbers were less than 3%.

However, utilities account for around 20% of total housing costs. This means the combination of gas outlays and utilities make up almost 9% of the average household budget. With much higher prices today, that number is surely around 10% of the total now and moving higher.

Experiencing higher prices on 10% of spending is going to inflict pain on the bottom line for many households.

The big question is this: How will higher inflation and energy prices impact consumer spending patterns?

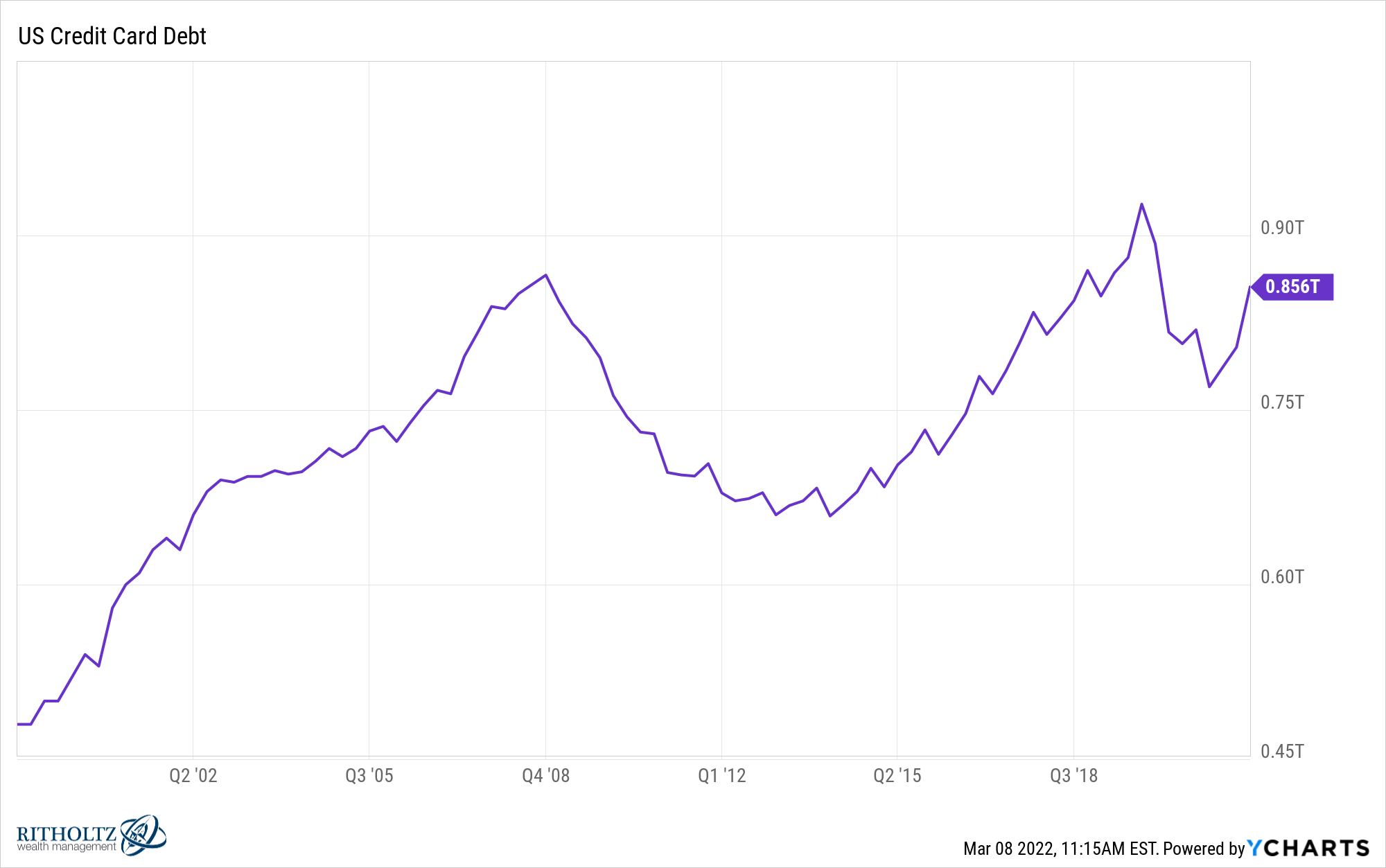

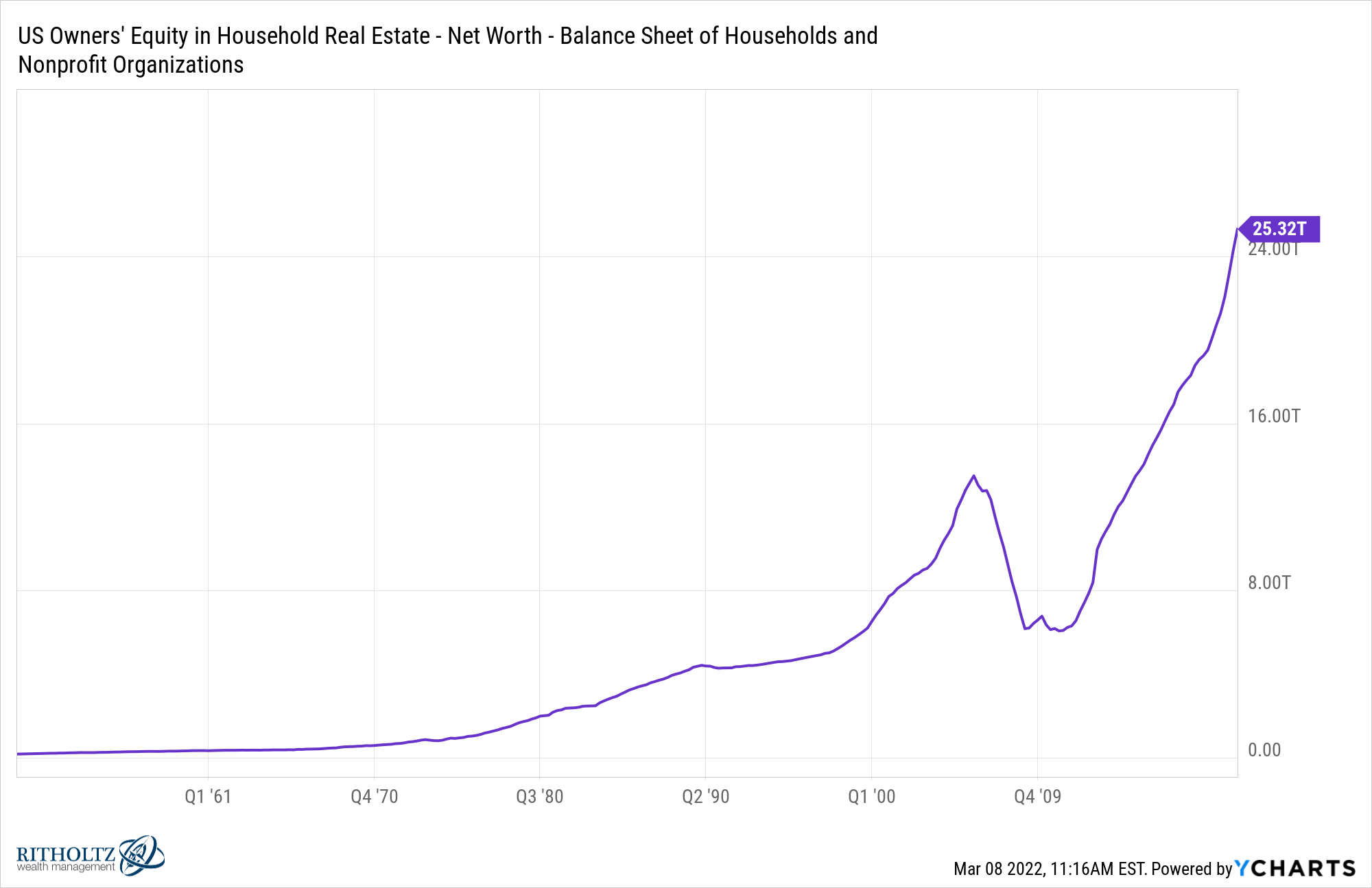

Consumers have spent the past two years cleaning up their balance sheets.

Credit card debt is down (although on the rise again):

Housing prices and therefore, home equity is way up:

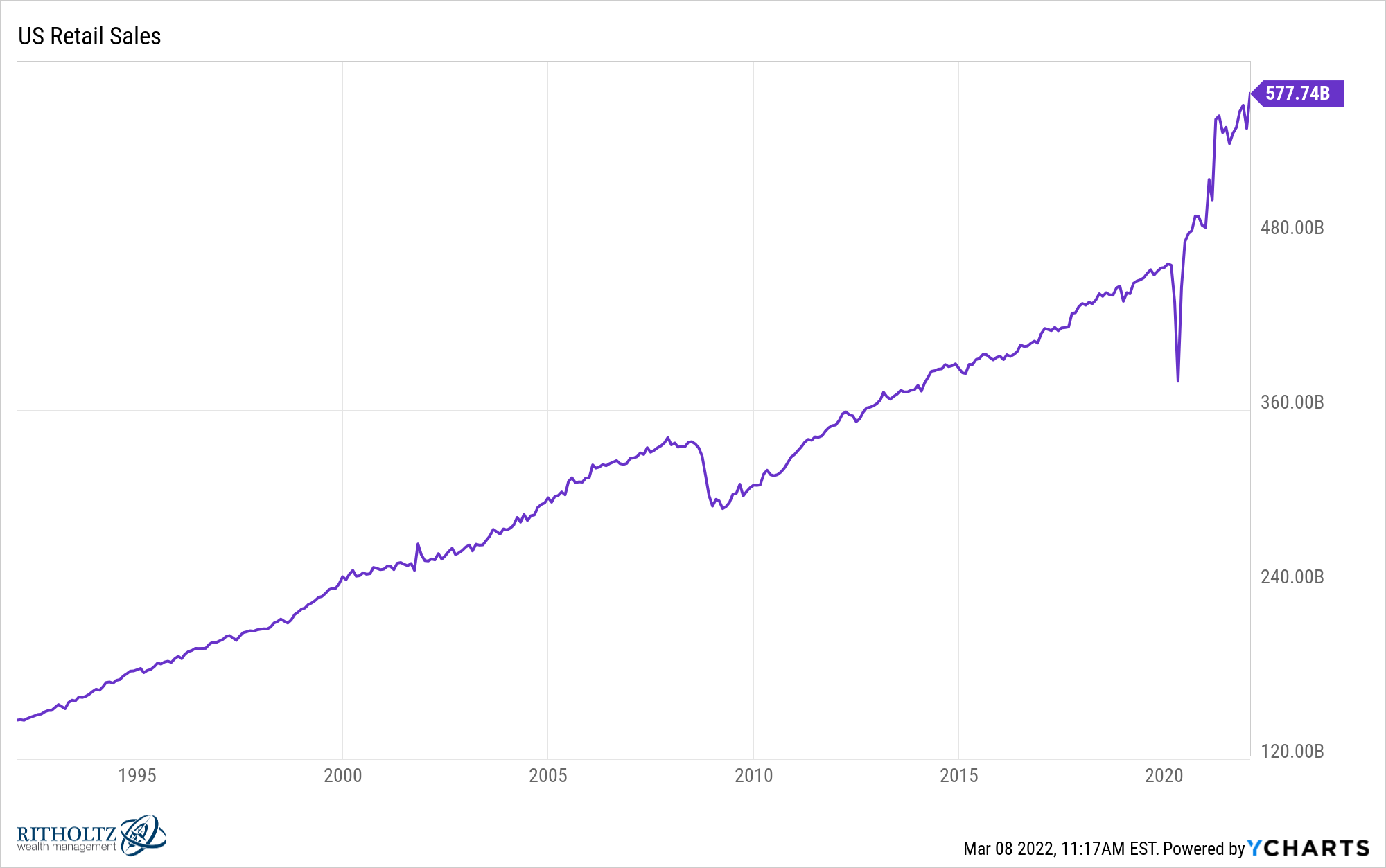

Retail sales are going bananas:

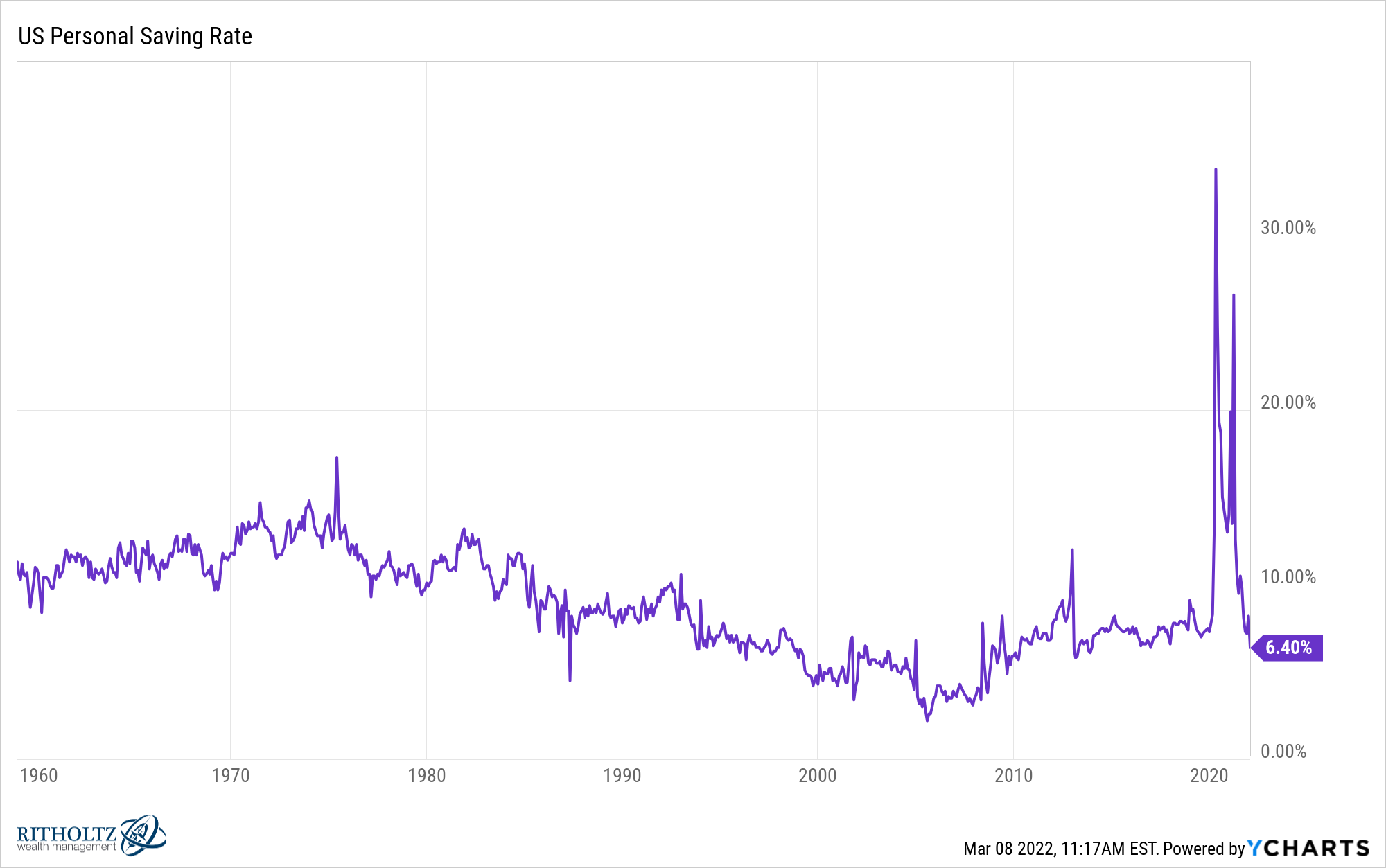

Personal savings rates spiked and are now back to pre-pandemic levels:

Inflation is no fun to deal with but you could make the case that households have been preparing for it for two years, whether they knew it or not.

Consumers have two options when it comes to inflation:

(1) Slow their spending to account for higher prices.

or

(2) Spend down their savings or go into debt to keep spending.

I’m not sure how this plays out.

But one thing I know for certain is Americans love to spend money. I would be surprised if households cut back their spending in a meaningful way, even with higher gas prices. The pandemic (fingers crossed) seems like it might be over. There is a lot of pent-up demand.

My guess is we’ll see much higher usage of debt and home equity in the coming years to match higher prices.

Consumers will continue to consume.

Further Reading:

Why Everyone Thinks the Inflation Numbers Are Wrong

1If we inflation-adjusted this number the high in gas would be something like $5.50 but this offers little solace to those feeling the pain at the pump right now.

2The usually caveats apply here — there is no such thing as an “average” household just like there is no such thing as an average inflation rate. Spending is circumstantial. But the relative importance of energy costs is the main takeaway here.