In August 2011, Gallup conducted a survey asking Americans to choose their best long-term investment. Gold was the resounding winner:

The timing on this one couldn’t have been worse.

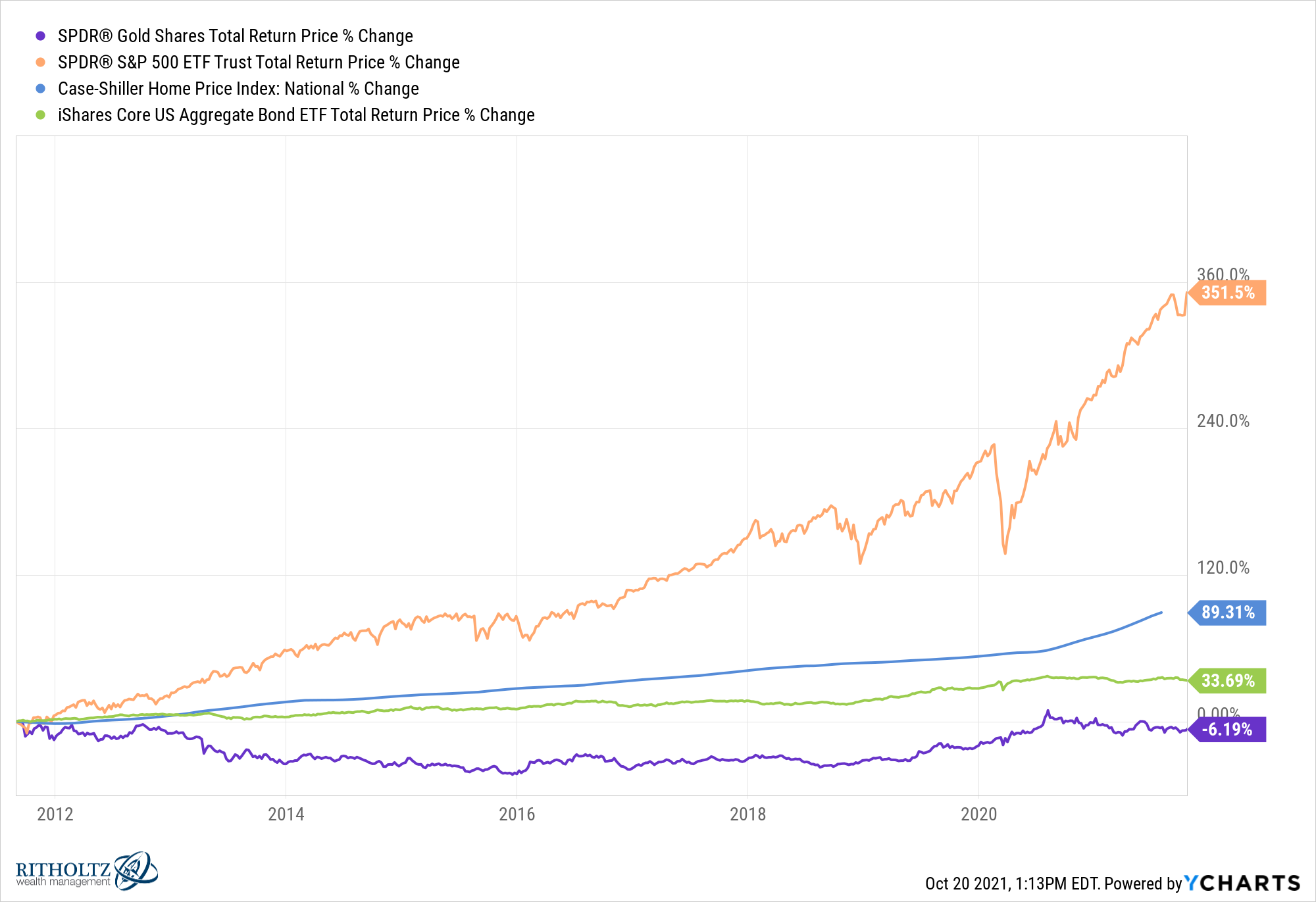

Here are the returns of gold, stocks, housing and bonds since then:

Gold has seen negative returns since the summer of 2011 while stocks and housing have been rocking. Even bonds are up a respectable 30% plus.

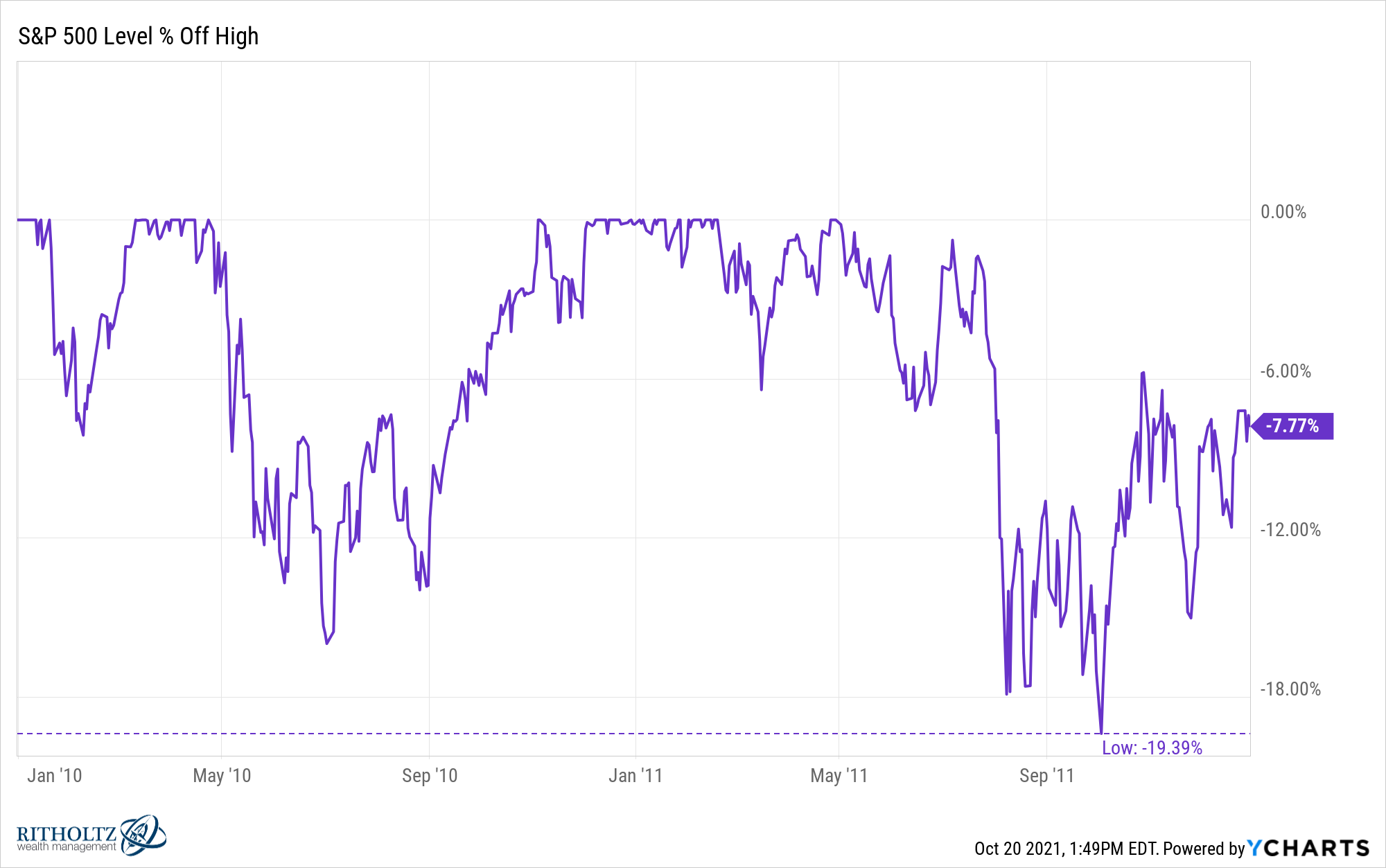

It is worth pointing out the market environment in which this occurred. The stock market was in the midst of what would turn into a near-20% correction:

Investors were still scarred from the Great Financial Crisis and every macro tourist was shouting from the rooftops about the coming hyperinflation from the Fed. Gold seemed like a slam dunk.

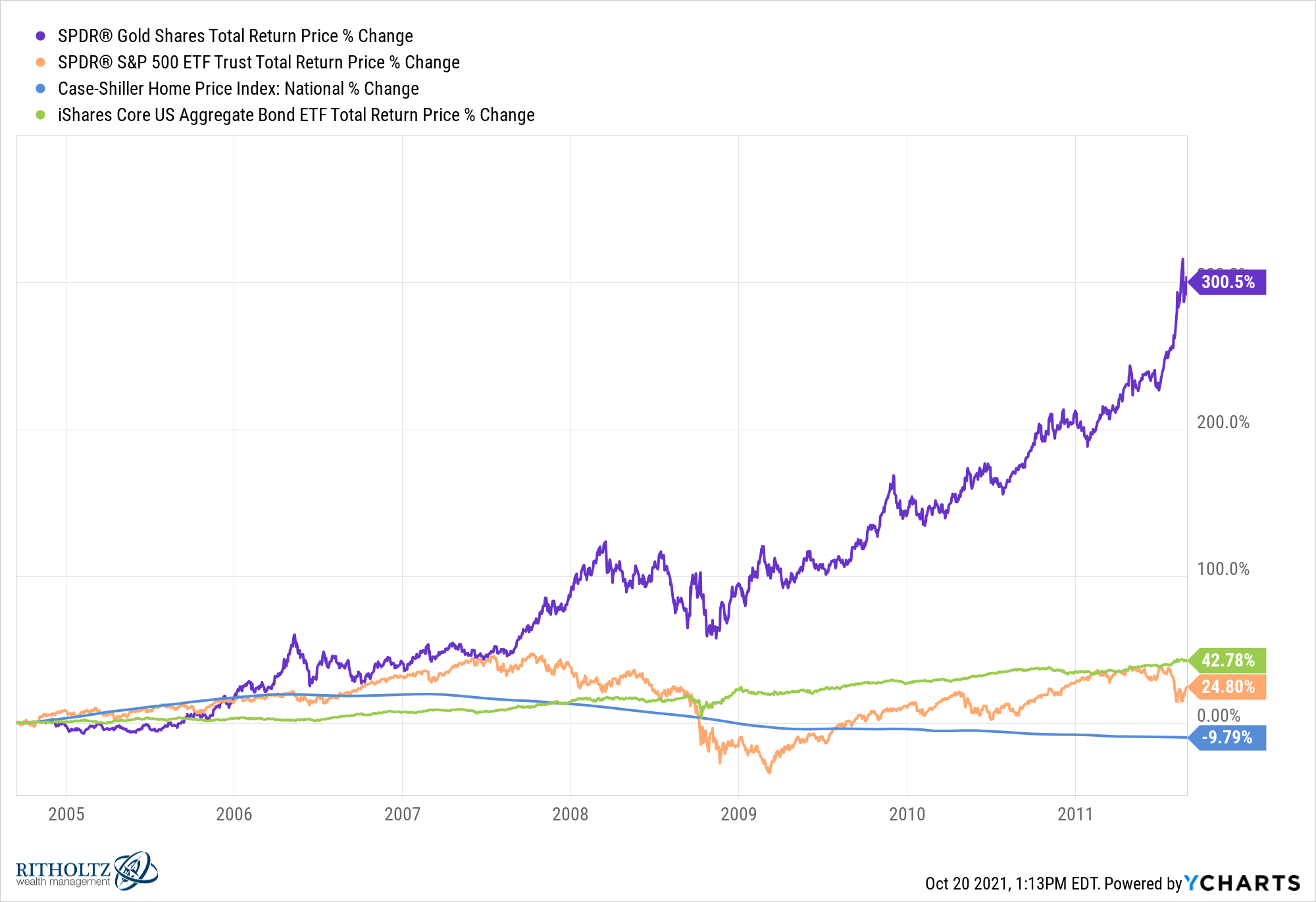

The problem is gold was already the best performer of this group by a landslide over the previous 10 years:

The stock market was coming out of a lost decade. The housing market was still a year or so away from bottoming from the crash. And 10 year treasuries were yielding around 2% so people figured rates had nowhere to go but up.

It makes sense investors become enamored with the best-performing assets.

You see others getting rich. You second guess your own investment decisions. You tell yourself you would have invested in that asset if you had the chance to do it all over again. This is how investors talk themselves into investing in whatever the best performing asset is at any given time.

It’s human nature to go with the herd.

If we had to do this exercise right now there are some obvious winners people have been piling into — crypto, tech stocks, start-ups, maybe even housing.

It sure feels like a great time to be a contrarian and bet against the biggest winners of the past decade or so.

Unfortunately, being a contrarian is much easier with the benefit of hindsight. Gold is a clear example but it surely wasn’t this clear at the time.

Remember John Paulson of The Greatest Trade Ever fame? You know, the guy who made billions betting against the housing market. In 2010, he created versions of his hedge fund that were denominated in gold. He created funds specifically to invest in gold as well.

People were beating this guy’s door down to give him money after his big short bet.

Whoops.

You could make the claim there are certain parts of the tech sector that have a similar feel today but going against the grain is harder than it sounds.

Being a contrarian requires patience but you also have to be right eventually. Simply betting against the stuff that’s working isn’t a useful strategy. You also have to nail the timing and have a catalyst that’s going to cause an investment to underperform.

Poor timing on a contrarian trade is indistinguishable from being wrong.

Market tops and bottoms are also rare.

Most of the time we’re somewhere in the middle of a market cycle, not the beginning or the end. This is why it’s important to avoid anchoring to price points from previous peaks or valleys. It can mess with your head if you’re constantly determining the value of something based on high or low price points.

Swimming against the current can also be a lonely and painful place to be. It’s more fun to go along with the crowd than it is to constantly bet against them. And although the herd mentality can lead investors astray at the extremes, most of the time the crowd is right.

Trends — in both directions — can last much longer than most investors assume is possible. Just because it feels like prices have detached from fundamentals doesn’t mean you’re going to see reversion in the other direction immediately.

Bull markets can last longer than you think. U.S. stocks were up 13% per year from 1946-1968. The market gained 17% per year from 1978-1999. The current run that began in 2009 has seen annualized returns of close to 19% since the bottom of the Great Financial Crisis lows.

On the other hand, it took 25 years for the market to reach 1929 highs following the Great Depression. The Dow was trading at 982 in early-1966. It was still at that same level in the fall of 1982 before breaking out to new highs for good.1

I’m sure people were calling for market tops for years during each of history’s great bull markets just like they were calling for bottoms for the entirety of the nasty bear markets.

Interest rates went nowhere for 30 years from the 1920s to the 1950s, then rose from the late-1950s through the early-1980s and have been falling for more than 40 years ever since.

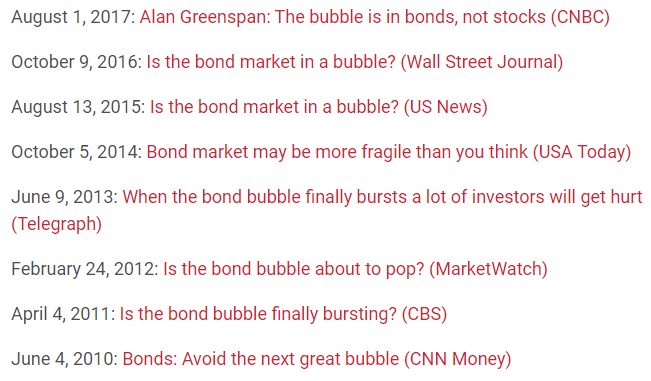

And of course people have been calling the current environment a bond bubble for years now:

Being a contrarian on gold in 2011 worked out well. Being a contrarian on bonds did not.

Look, I’m not saying you should always follow the trend. Of course that can be terrible advice, especially at the extremes. I just know that I’m not smart enough to know when the current cycle will end.

Therefore, I’m going to avoid going to either extreme — I’m not going all-in exclusively on everything that’s worked well in the recent past just like I’m not going all-in betting against those same recent winners by trying to be a contrarian.

Some investors are more comfortable trying to be a hero.

I’m more comfortable diversifying and admitting my limitations.

Being a contrarian and making money simultaneously is hard.

Further Reading:

What Has the Stock Market Taught Us Since 2010?

1The nominal returns for both of these periods were still positive because dividend yields were higher but these were still awful times to be an investor for the most part.