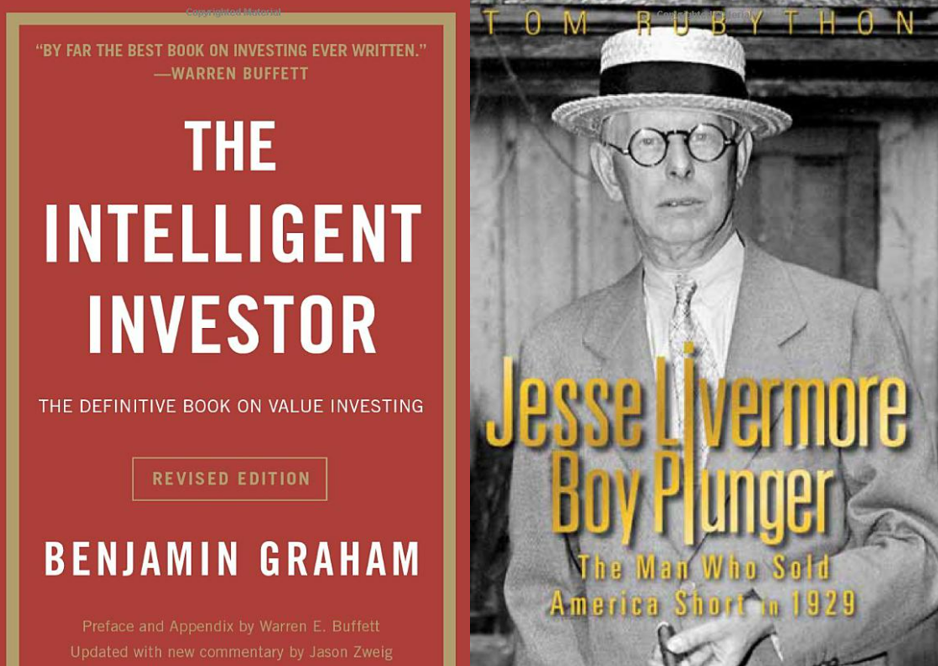

Benjamin Graham and Jesse Livermore are two of the most well-known investors in history.

Investors and traders alike still liberally quote Graham and Livermore on a regular basis despite the fact that both made their bones investing in the early part of the 20th century.

If we do a tale of the tape, you’ll notice many differences between these two legends.

Graham was the consummate long-term bottom-up fundamental investor.

Livermore was a trader who was only interested in price and trend.

Graham viewed investing in stocks as owning a piece of a business.

Livermore viewed investing in stocks as trading a piece of paper based on the behavior of other market participants.

Graham got crushed investing during the Great Depression.

Livermore made $100 million in a matter of days shorting the market in 1929.

Graham was focused as much on risk as reward which was symbolized by his focus on a margin of safety.

Livermore was more reckless with risk which is why he made and lost his fortune on numerous occasions.

Despite their differences, these two do have something in common.

If you’ve never read Graham’s The Intelligent Investor, the most important concepts are covered in chapters 8 and 20.1

In chapter 8, Graham introduces the story of Mr. Market as a way to illustrate the manic behavior of investors in the short-term. Chapter 20 covers the idea of margin of safety as a way to better understand risk management.

Both chapters still hold up to this day despite the fact that the book was originally published in 1949.

But the rest of the book can be a tad on the dry side. There are a lot of equations. Most of the stocks analyzed are railroad companies. And there is the framework for how Graham thought about security analysis.

Two-and-a-half decades after the book’s publication, Graham questioned whether his initial ideas about valuing stocks still held water.

Shortly before his death in 1976, Graham sat down for an interview with Charley Ellis that was later published in the Financial Analysts Journal. He had completely changed his tune about the prospect for security analysis leading to superior opportunities in the market:

I am no longer an advocate of elaborate techniques of security analysis in order to find superior value opportunities. This was a rewarding activity, say, forty years ago, when our textbook “Graham and Dodd” was first published; but the situation has changed a good deal since then. In the old days any well‐trained security analyst could do a good professional job of selecting undervalued issues through detailed studies; but in the light of the enormous amount of research now being carried on, I doubt whether in most cases such extensive efforts will generate sufficiently superior selections to justify their costs.

In another interview, Graham explained why it was becoming harder and harder to outperform:

Everyone on Wall Street is so smart that their brilliance offsets each other. And that whatever they know is already reflected in the level of stock prices, pretty much. Consequently, what happens in the future represents what they don’t know.

True to form as a value investor, Graham was probably early with these comments but this is more true now than ever.

In his book, Graham lays out the idea of buying net-net companies, which were stocks that were trading at a market cap below the level of their assets or cash on hand. He was shooting fish in a barrel with these investments because they were trading at a discount. You just had to wait for investors to realize the disconnect.

It’s more or less impossible to find investible companies that are valued at these levels anymore.

Livermore also saw his first-mover advantages in the markets slowly fade away but the reasons were different than Graham’s.

The Boy Plunger made his first real money in the bucket shops of the early-1900s. Bucket shops were kind of like Robinhood without the app or any sense of rules or regulations. It was the Wild West and Livermore basically took them for all they were worth.

In fact, he was so good at reading the tape and making money by chasing short-term market trends, he would eventually be forced to wear disguises to place his trades at these bucket shops since so many had banned him from trading.

After starting 1930 with a personal fortune of $100 million, which including a number of real estate properties and a yacht, Livermore was dead broke by 1934. A combination of leverage, an awful stock market environment and a number of bad bets did him in.

This was the fourth time in his career Livermore had gone broke. Every other time he came back stronger and made even more money than his previous windfalls. However, he was never able to capture lightning in a bottle again and for good reason.

The regulators caught up to him. Tom Rubython explains in his book Jesse Livermore: Boy Plunger:

The rules of the stock market, and what constituted acceptable behavior, had changed with the advent of Franklin Roosevelt’s Securities & Exchange Commission in 1934, which made life very difficult for the old breed of traders like Livermore. The new SEC laws had gradually worn him down. Now, almost every method he had used to amass four large fortunes, which briefly had made him one of the richest men in the world, were outlawed and illegal. As he sat in his office each morning, all he could do was think about the glory days, long since passed, and how to wile away the hours until lunch.

At first, Jesse Livermore dismissed the new laws, and it was only when he read the statutes in detail that he realized that all the provisions in the new Securities Act seemed to be aimed straight at him. Stunts he had pulled off in the past were now illegal.

The formation of the SEC following the Great Depression was a disaster for Livermore and other speculators. Certain speculative activities that were once legal were now punishable by large fines and even prison time.

Livermore made his fortune during a time in which there were no rules.

Once those rules had changed it became impossible for him to trade his way to riches once again. In 1940, he took his own life and died broke.

Markets are constantly changing and evolving.

Every day there is more information, analysis, opinions and data available. Our knowledge of market history itself can change how people allocate and view the markets.

In the 1950s, the S&P 500 consisted of railroad stocks, utilities and industrials. Financial stocks weren’t added until the late-1970s.

In fact, the S&P 500 itself wasn’t officially created until 1957. All of the data people like me use before than time has been recreated.2

Hedge funds basically operated like Jesse Livermore in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s to gain an edge. Then Reg FD came along in the year 2000. The performance of these funds has suffered now that corporate information must be disseminated to everyone at the same time.

You can still learn from legendary investors and traders. Market history can still help give you insights into potential risks.

But markets change. Investors adapt. Rules are updated. Advantages slowly get arbitraged away. Strategies that outperformed in the past don’t work as well in the future once everyone knows about them.

This is true for normal investors and legends alike.

Further Reading:

The Psychology of Betting Big and Losing it All

1This is helpful to know since the book is 500+ pages long.

2The S&P 90 was created in 1926 so that helps.