The crypto starter pack consists of the following:

Laser eyes (you want to be part of something bigger than yourself).

A minimal level of distrust or a rebellious streak (you want to shake up the current system).

An appetite for risk (the volatility in this space is wild).

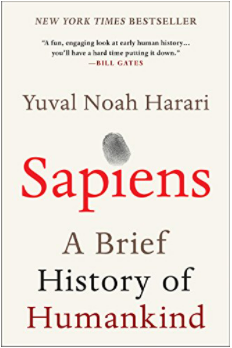

And the book Sapiens (you understand network effects and the importance of storytelling).

If you haven’t mentioned Sapiens in a Twitter thread, podcast interview or Substack letter, do you even own an insanely large amount of crypto?

It’s the bible for crypto evangelists that is used as both an explainer and justification for everything that’s transpired in that space.

Why?

The book details how Homo sapiens managed to cross the threshold from small tribes to cities with millions of people living in them and organizations with thousands of employees:

The secret was probably the appearance of fiction. Large numbers of strangers can cooperate successfully by believing in common myths.

Telling effective stories is not easy. The difficulty lies not in telling the story, but in convincing everyone else to believe it. Much of history revolves around this question: how does one convince millions of people to believe particular stories about gods, or nations, or limited liability companies? Yet when it succeeds, it gives Sapiens immense power, because it enables millions of strangers to cooperate and work towards common goals. Just try to imagine how difficult it would have been to create states, or churches, or legal systems if we could speak only about things that really exist, such as rivers, trees and lions.

How can you explain fake internet money creating trillions of dollars in wealth out of thin air?

Story-telling.

How do meme stocks add billions of dollars for no reason?

Collective action.

How did Tesla defy the odds to become one of the biggest companies in the world?

Tesla supporters are about as close to a religion as it comes for a stock.

Why are JPEGs selling for millions of dollars?

We’re status-seeking creatures.

Sapiens explains it all and it’s likely going to remain the bible for the 2020s market environment until something else comes along to knock it off its perch.

This got me thinking about other books that defined specific market cycles.

Here’s what I came up with by decade going all the way back to the 1940s:

1940s: Where Are the Customers’ Yachts? by Fred Schwed

This book was originally published in 1940 and remains the funniest investment book ever written. Few investors deserved to take themselves seriously back then since no one really knew what they were doing so satire was a perfect fit.

Schwed did a wonderful job exposing Wall Street and its customers alike for taking things too far in the run-up to the Great Depression.

He wrote, “The burnt customer certainly prefers to believe that he has been robbed rather than that he has been a fool on the advice of fools.”

The 1930s were such a harsh decade that it’s fitting the best book from that time period was on the lighter side of things.

1950s: Security Analysis by Benjamin Graham & David Dodd

The 1950s bull market put an end to 20+ years or so where markets were more or less a barren wasteland following the depression.

Investment analysis in the 1920s, 30s and 40s more or less consisted of looking at dividend yields, buying stuff that was going up and scams.

The entire idea of fundamental analysis wasn’t really a thing since data was sparse, information was hard to come by, and no one was teaching this stuff.

Benjamin Graham’s tome on fundamental analysis helped usher in a new era on Wall Street. The entire industry was finally beginning to become more professional.

1960s: The Money Game by Adam Smith

If the 1950s ushered in a new era of fundamental investors, the 1960s took it to another level.

The star mutual fund manager was born in the 1960s and Smith documents many in his book. But the book was also one of the first to frame the markets, and the humans that move them, as irrational in nature.

It’s a self-described book about “image and reality and identity and anxiety and money,” which sounds vaguely familiar in today’s marketplace.

Adam Smith (aka George Goodman) also wrote, “If you don’t know who you are, this [the stock market] is an expensive place to find out.”

The bull market of the 1950s spilled over into the early-1960s but by the end of the decade many investors learned just how expensive it could be.

1970s: The Go-Go Years by John Brooks

From 1949-1968, the S&P 500 was up nearly 15% per year, one of the greatest 20 year stretches in market history. Then from 1969-1979, the market returned just 4.5% per year. But things were even worse than that because of the sky-high inflation of the 1970s.

Inflation ran just 1.9% per year from 1949-1968 but jumped to an annual rate of 6.3% from 1969-1979. So nominal returns were lower but real returns were negative. It was a brutal stretch for investors in both stocks and bonds.

John Brooks chronicled the end of the Go-Go Years of the 1960s in his book by the same name. It was written in 1973, the same year a nasty 50% bear market began.

Brooks was right about Wall Street in the 1970s when he wrote, “Wall Street is heading toward transforming itself into an impersonal national slot machine — presumably fairer to the investor but of much less interest as a microcosm of America.”

This statement pairs well with the infamous Death of Equities story on the cover of Business Week in 1979.

It was the end of an era but it wouldn’t last long. The markets certainly became a microcosm of America beginning in the 1980s.

1980s: Liar’s Poker by Michael Lewis

The 1980s saw the rebirth of Wall Street.

Inflation slowed, interest rates began to fall, high yield bonds came into vogue, LBOs made private equity titans wealthy, the stock market took off again and Gordon Gekko became a national hero for a certain group of people.

No book captured the zeitgeist of Wall Street in the 1980s better than Liar’s Poker because Michael Lewis told the story as an insider at Soloman Brothers.

1990s: One Up on Wall Street by Peter Lynch

If the 1980s was the rebirth of Wall Street the 1990s spawned a new class of individual investors.

The share of U.S. households that owned stocks was less than 20% in the early-1980s. By the end of the 1990s that number shot up to 50%.

Peter Lynch’s “buy what you know” strategy was a fitting mantra for all of these first-time newbie investors.

Many of those noobs got crushed in the next decade.

2000s: The Intelligent Investor by Benjamin Graham

The late-1990s was dominated by growth stocks but the dot-com bust saw the tech-heavy Nasdaq fall more than 80% in the ensuing crash.

That sent investors into the loving arms of Warren Buffett and his mentor Ben Graham’s book. Although The Intelligent Investor was originally published in 1949 it still sells.

The 2000s was the decade of bottom-up fundamental investors. Hedge funds that shorted expensive tech stocks and went long value stocks made a killing in the early part of the decade. The number of hedge funds in existence tripled from more than 3,500 in 2000 to more than 10,000 by the end of the decade.

Every investor wanted to follow in the footsteps of the Oracle of Omaha.

Unfortunately for the Buffett disciples, it’s been a tough road ever since for fundamental investors.

2010s: Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Behavioral finance has been around for a while but it finally went mainstream in the 2010s. Reading Kahneman’s 400+ page book on the irrationality of human beings became a badge of honor in the finance world.

The bull market in behavioral finance played a role in moving trillions of dollars into index funds and ETFs, a huge win for individual investors.

And just when we thought everyone was going to be boring old index investors, there was a boom in crypto, Robinhood, NFTs, meme stocks and day-trading.

I wish I could tell you what comes next. Maybe future explainers will come in podcast form instead of books.

Further Reading:

TL;DR: The Best Finance Books in One Sentence