Real GDP growth in the United States came in at an annualized 6.4% in the first quarter. The Fed now estimates 7% GDP growth for all of 2021.

That would be the highest level of growth since 1984.

The latest inflation rate checked in at 5% over the previous 12 months.

That is the highest level of inflation since 2008.

Granted, these numbers are coming off a low base because of the pandemic. We can’t expect this to last.

But with all of the government spending, rising home prices, supply shortages and improved consumer finances, it makes sense to bump up the economic growth and inflation numbers from what they were pre-pandemic.

We may not get 4-5% sustained inflation but we could see 2-3% which would be a step up from the 1-2% post-2008 recovery. And we may not see 6-7% real GDP growth continue but it’s certainly possible for 3-4% for a few years as opposed to the 2% or so we’ve become accustomed to.

I don’t know if these things will happen since the economy is notoriously difficult to predict but the probability for both higher growth and higher inflation is higher than it’s been in some time.

Yet interest rates remain stubbornly low.

So why aren’t rates higher than this?

Why are bond investors still accepting these paltry yields if the macro environment is one of higher growth and inflation?

It’s impossible to pinpoint for sure and maybe this is short-lived but here are some reasons this could be the case:

Demographics. Baby boomers hold something like $70 trillion in wealth. They own most of the financial assets. Ten thousand people from this cohort are retiring every day through the end of this decade.

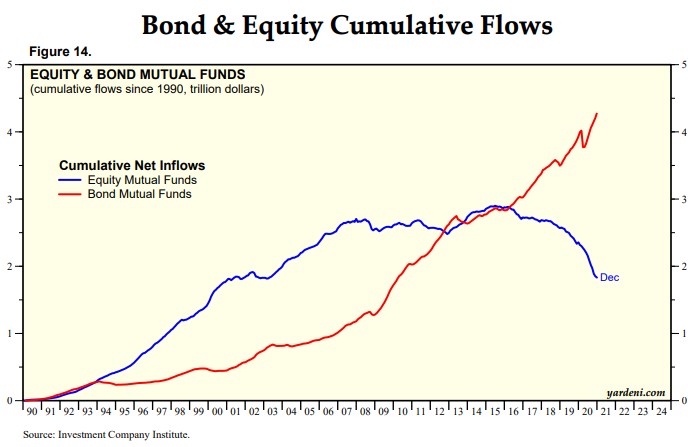

When you combine this fact with the professionalization of financial services and the advent of things like targetdate funds, you get this (via Ed Yardeni):

In the midst of a 12 year bull market in stocks we’ve actually seen net outflows from equities and surging inflows to bonds.

As investors age, they tend to diversify their portfolios to include safer assets like bonds since they don’t have as much time or future earnings power to make up for losses in the stock market.

If the demand for bonds is there, macro factors don’t mean as much as the flows.

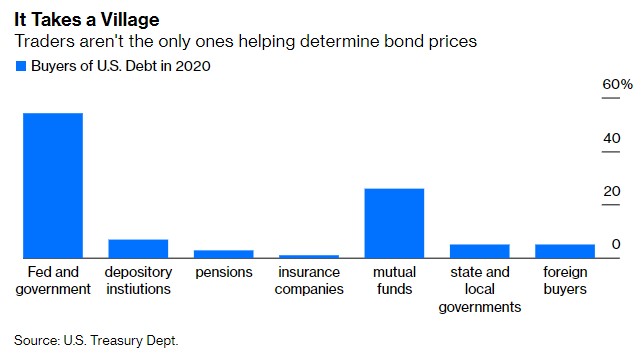

The Fed. Demand for bonds is not just coming from the investor class either. Allison Shrager at Bloomberg recently showed who purchased all of the U.S. government debt in 2020:

Mutual funds were big buyers but they were dwarfed by the Fed, who stepped up to buy up government debt in a big way last year.

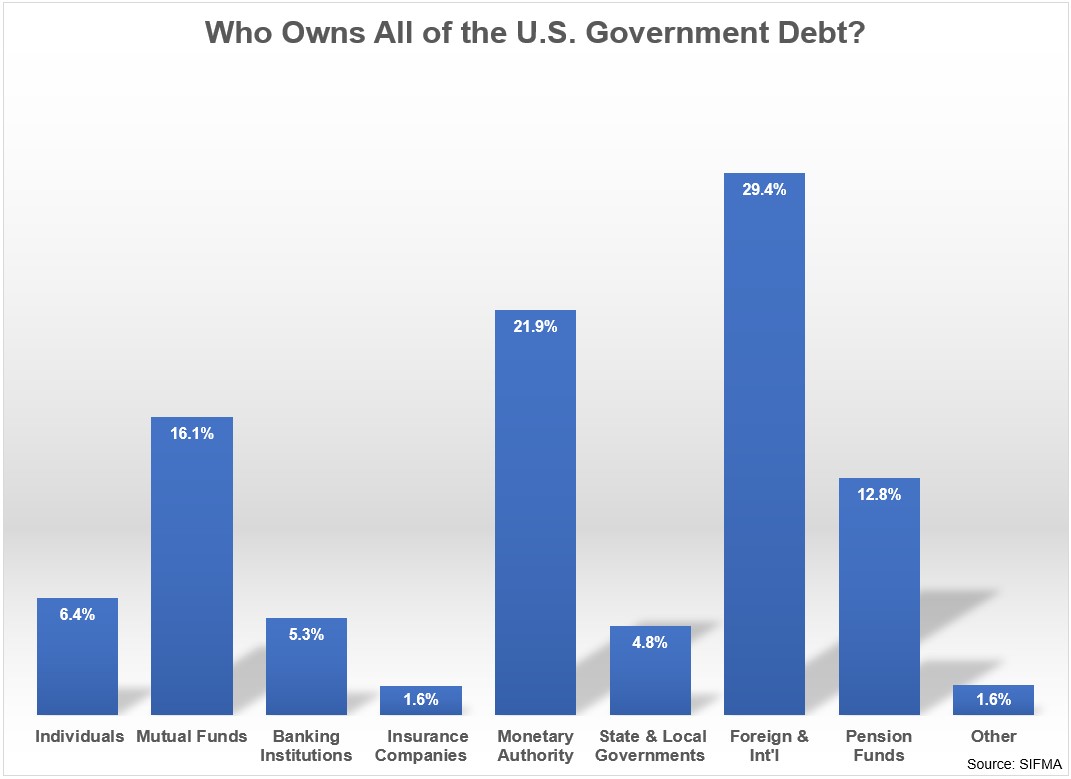

The pandemic was an aberration so here is the breakdown by overall holdings:

When you add up individuals and mutual funds that gets you to about the same level as Fed holdings at around 22%. Foreign governments and investors are still the largest holders at almost 30%. This means around three-quarters of U.S. government debt is held by investors, foreigners and the Fed.

Can the Fed keep a lid on interest rates if they keep buying? It’s possible.

Can the government afford to let rates rise much higher in the future with all of our debt obligations? We shall see.

A repricing of risk-free returns. What if investors aren’t supposed to earn high rates of return on risk-free government bonds?

What if those days are past us because of technological innovation, lower barriers to entry for investors, more access to information and a changing landscape in the markets?

Why should investors be compensated for holding an asset that is guaranteed to pay you back?

I don’t know the answers to these questions but it’s worth considering if the days of high yields on U.S. treasuries are behind us.

A more mature economy. The United States has the biggest, safest financial markets on the planet. We were forced to pay higher rates of interest in the past because our economy wasn’t as stable and mature as it is today. The wealthier we have become the lower rates have gone.

There is precedent for this scenario.

In The Birth of Plenty, William Bernstein discusses how the maturity of an economy affects interest rates over time:

Interest rates, according to economic historian Richard Sylla, accurately reflect a society’s health. In effect, a plot of interest rates over time is a nation’s “fever curve.” In uncertain times rates rise because there is less sense of public security and trust. Over the broad sweep of history, all of the major ancient civilizations demonstrated a “U-shaped” pattern of interest rates. There were high rates early in their history, following by slowly falling rates as the civilizations matured and stabilized. This led to low rates at the height of their development, and, finally, as the civilizations decayed, there was a return of rising rates.

People have been calling for an end to this stabilization for decades but it hasn’t happened. The trust in our system could decay someday but you would have a hard time predicting when that would happen.

I wouldn’t want to bet against the United States but you never know.

Nothing lasts forever in the financial markets so who knows how long these forces can counteract the macroeconomy.

The only thing I’m sure about at the moment is we live in confusing times, economically speaking.

Further Reading:

Predicting Inflation is Hard