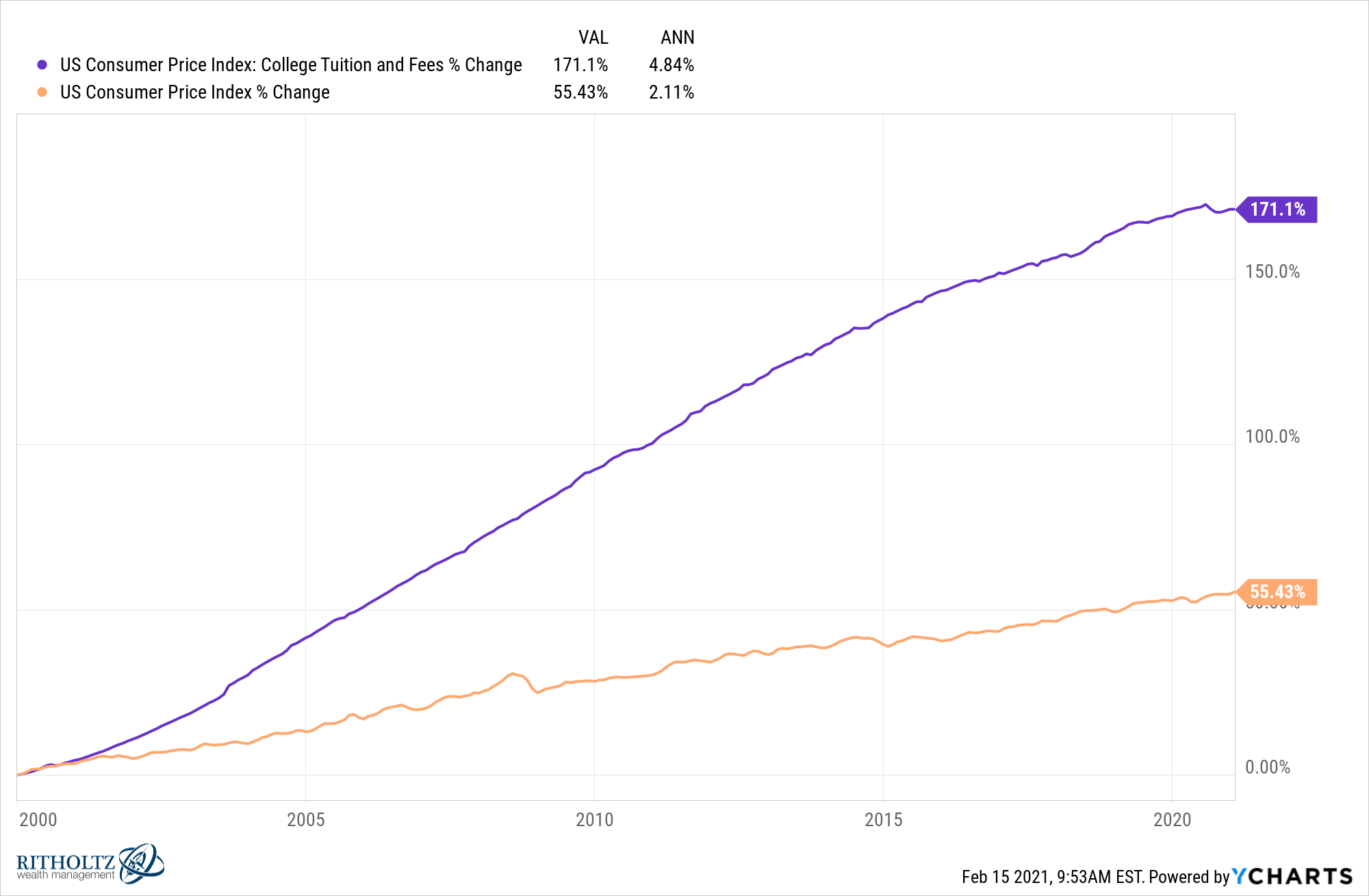

Since the turn of the century the cost of college has risen at nearly 2.5x the rate of inflation in the United States:

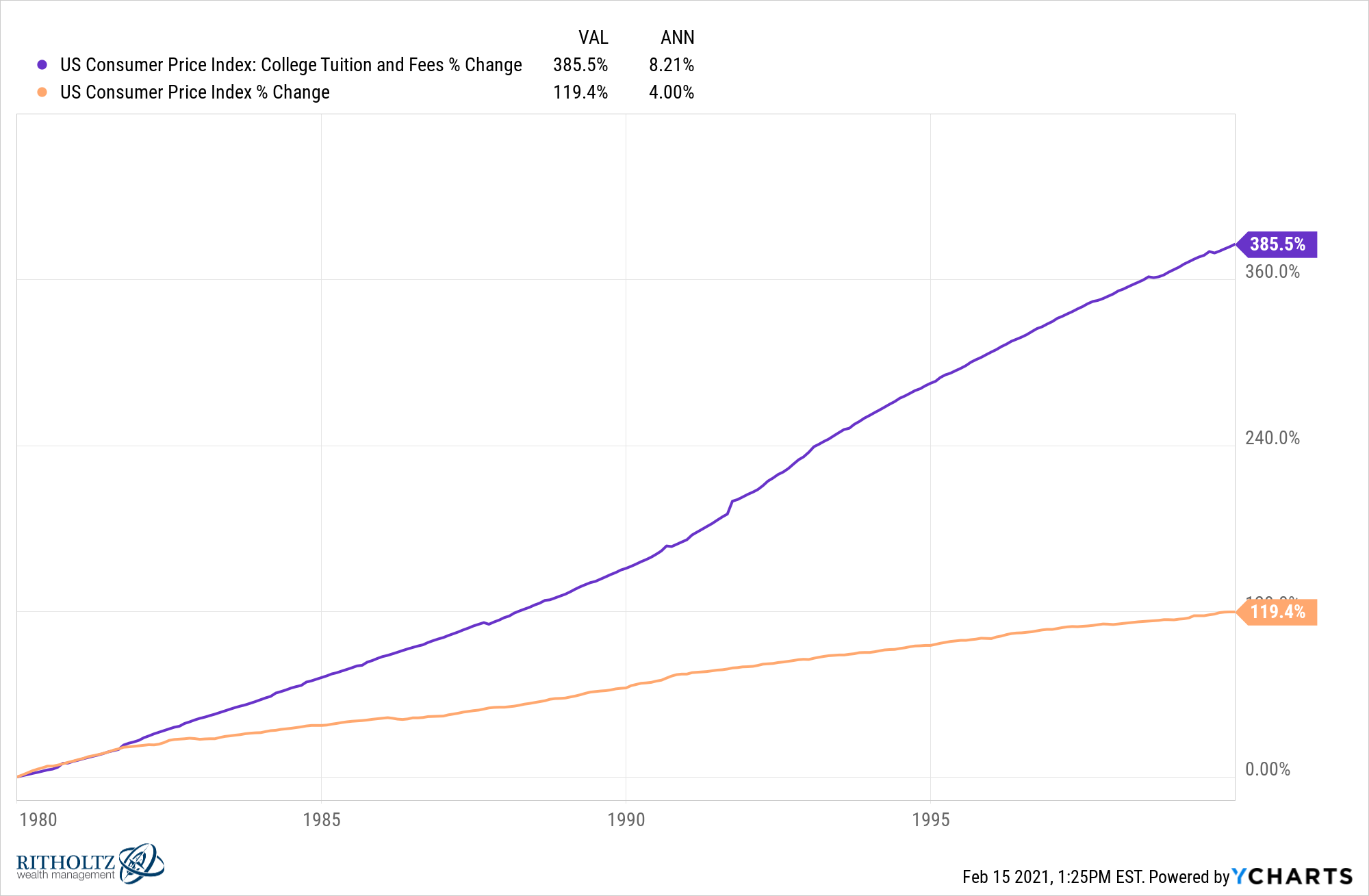

Prices rose even faster in the 1980s and 1990s:

It’s hard to imagine prices rising at double the rate of inflation for going on four decades now.

So why does the price of college continue to rise?

These are the main theories:

- Amenities like lazy rivers and rock climbing walls are out of control.

- There are too many administrators.

- College professors make too much money.

- Demand remains high because college grads make more money (on average).

- State funding has been cut to many public universities.

There is another theory that doesn’t get much play — what if prices aren’t actually rising this fast? What if the sticker price of college is an illusion for most people?

Ron Lieber shares some statistics in his new book The Price You Pay For College, that kind of blew me away:

- The average first-year, full-time student in 2019-20 got a discount of 52.6% off the list price.

- The average grant for public universities is more than $4,100 per year.

- 89% of students at private colleges get a need-based or merit-based discount on tuition.

- People who do pay full freight are those who attend more selective schools, rich people and international students.

Lieber notes, “On average, what families are actually spending hasn’t gone up by completely unreasonable amounts over the past twenty years, even as the list prices have gone to the moon. That’s because the discount rate has gone up steadily over time as well.”

The average price people pay for private colleges, including room and board is just shy of $24,000 a year. Granted, this is still a high number but is less than the list price at many public universities (where people are also paying below sticker). Prices paid at in-state public universities, including room and board, are around $15,400 a year (after accounting for discounts).

Are these numbers much higher than they were in the past? Absolutely.

Are they as bad as some people make them out to be? Not really.1

So why don’t these schools just lower the list price? Lieber explains:

Rice University, which has a giant endowment, subsidized its tuition for years with the earnings from it but came to believe that its low list price suggested that it wasn’t as good as Harvard or even Emory. It raised its price dramatically and never looked back. Mount Holyoke College had success with regular double-digit percentage in the 1980s; the average SAT scores of students there rose in the wake of them. Even in the thick of the application process, plenty of families never learn what percentage of students at any given school are not actually paying the list price. So colleges try to maintain the glossy shine of high retail rate as best they can.

Right or wrong, most people associate higher prices with higher quality.

So where does all of that tuition money go?

Roughly 70% of the cost of college goes to administrators and teachers. So the biggest cost of college is labor and I don’t see colleges deciding to scrimp on these costs anytime soon.

The other big reason is states cut funding. One study cited by Lieber found cut-backs from the 2001 and 2008 recessions account for 80% of the price hikes at public universities.

Unless we get a complete online overhaul of the college experience from Apple or Google, the only real shot we have at lowering tuition would have to come from the government. So either taxes get raised or tuition costs continue to rise at most in-state public schools.

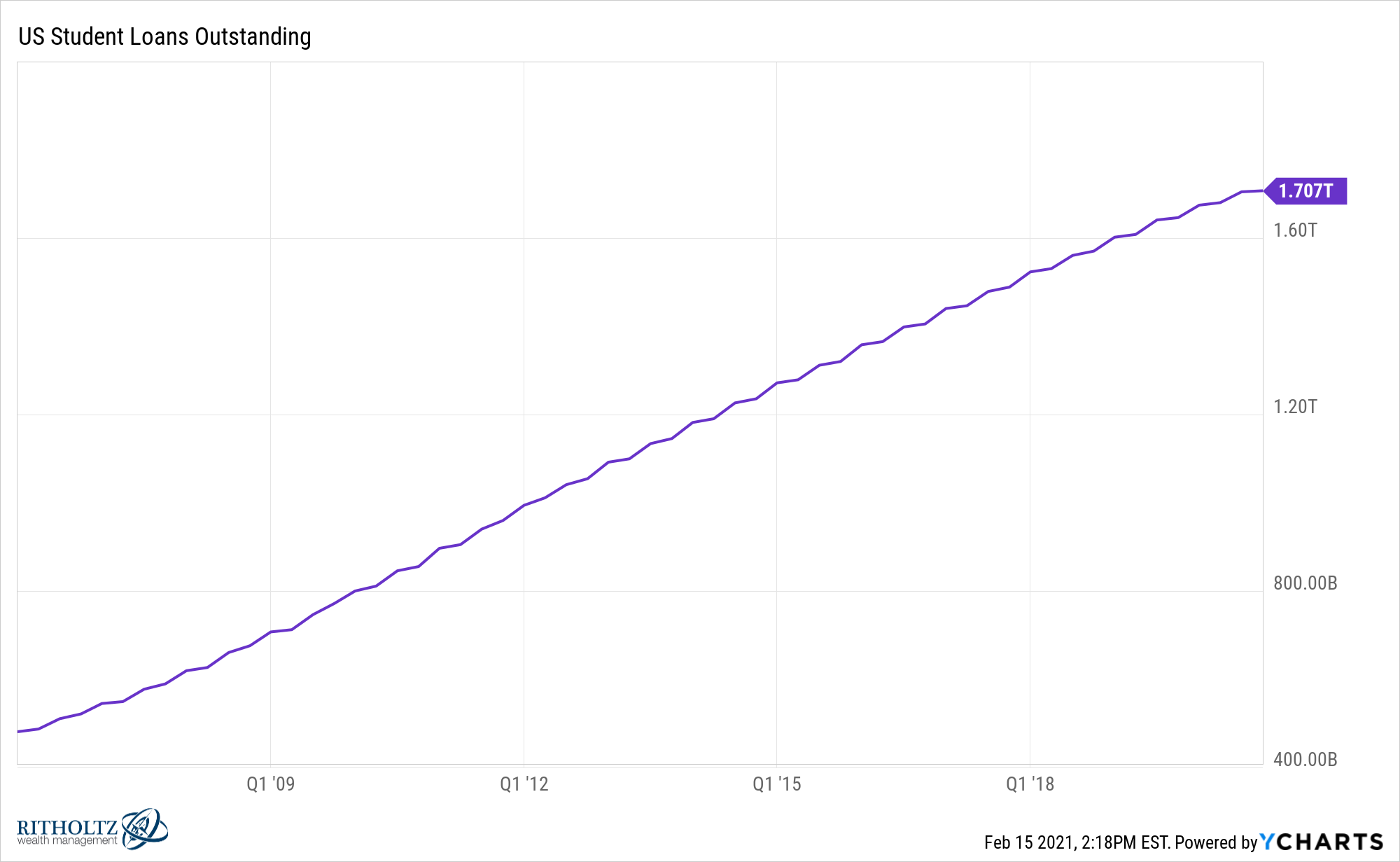

For some reason, the government has not stepped in to help things on the tuition side of the equation but it sounds like one way or another they are going to be helping on the student loan side of things. Student loans are still a big number:

Whether President Biden pushes through a plan to eliminate a certain amount of student loan debt or not, it sounds like a big piece of this $1.7 trillion will be written off eventually.

The Wall Street Journal reported this past November that number could be upwards of $435 billion:

The U.S. government stands to lose more than $400 billion from the federal student loan program, an internal analysis shows, approaching the size of losses incurred by banks during the subprime-mortgage crisis.

The Education Department, with the help of two private consultants, looked at $1.37 trillion in student loans held by the government at the start of the year. Their conclusion: Borrowers will pay back $935 billion in principal and interest. That would leave taxpayers on the hook for $435 billion, according to documents reviewed by The Wall Street Journal.

The Journal calls this number a “loss” for taxpayers but it’s really a gain for those who would have those loan amounts go away. Basically there are rules in place to have your loan forgiven based on maximum repayment time, working for a nonprofit and payments tied to income level.

So Democrats forgiving loans now will likely be in some ways loans that would have been forgiven in the future anyway.

I’m not saying there isn’t room for improvement in the price of college tuition or the way the student loan industry is set up. The government has let down a lot of young people in their handling of both areas.

But maybe the numbers aren’t as bad as some people have led you to believe.

Further Reading:

Is College Worth the Cost?

1A four-year public university education costs about as much as all of those fully-stocks trucks and SUVs you see all over the roads today. One of these things is a good investment while the other is not. The New York Fed estimates the annual return on investment in college is around 14% per year.