Since late March the U.S. dollar has fallen almost 10% against a basket of other currencies around the globe. Some of this selloff may have to do with the fact that the dollar shot up so much at the outset of the crisis, as people saw the dollar as a safe haven.

But some investors are now wondering if this is a sign of a long-term trend reversal. The dollar has been rising steadily since the end of the Great Recession as the U.S. has been seen by many as the cleanest shirt in a dirty laundry hamper.

That may be changing if for no other reason than currency moves are cyclical. There are other reasons to consider a new cycle could be starting. Gold is now hitting all-time highs last seen in 2011. People are worried about the potential for inflation now that we’ve experienced so much fiscal stimulus.

No one knows for sure whether the dollar decline will continue, but if it does there would be a number of implications for your portfolio.

A weak dollar would benefit foreign stock market companies and funds held by U.S. investors. Those who own international stocks are subject to currency fluctuations, so if the dollar falls, that means your foreign stocks are worth more once they’re converted to our currency. One of the biggest reasons international stocks have badly lagged U.S. stocks in recent years is because the dollar has been so strong.

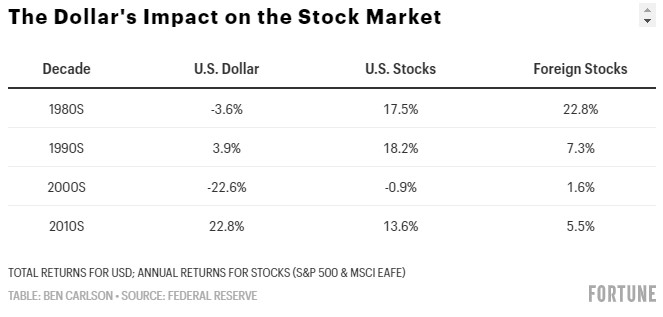

The performance of the dollar, U.S. stocks, and foreign stocks by decade offers a clear picture of this relationship:

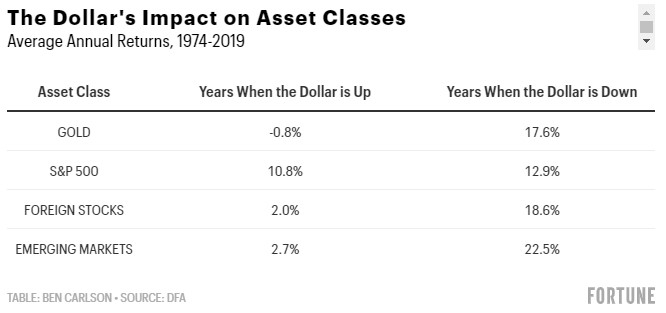

The dollar’s impact can also be seen on a number of other asset classes including gold and emerging markets:

When the dollar is up, gold, foreign developed, and emerging-market stocks tend to perform poorly. And when the dollar is down, gold, foreign developed, and emerging-market stocks tend to perform admirably.

In years of dollar weakness, foreign stocks have risen 85% of the time, gold is up 80% of the time, and emerging markets have advanced 65% of the time.

On the other hand, in years of dollar strength, foreign stocks are up just 62% of the time, gold is only up 42% of the time, and emerging markets rose just 50% of the time.

This makes sense if you consider how things work from the perspective of a U.S. traveler going overseas (hopefully, we can do that again in the near future). When you convert your U.S. dollars into the foreign currency for spending purposes, your money goes further when the dollar is rising. Alternatively, when the dollar is falling, your money doesn’t buy as much internationally.

The dollar is, of course, not the only variable that affects these markets and prices, but it plays a larger role than most investors realize. And although currencies are volatile in the short-term, over the long-term the changes between countries tend to work themselves out. In fact, the dollar is basically at the same point now as it was in the year 1978.

It’s still too early to tell if the recent dollar weakness is a sign of things to come or a short-term blip on a longer-term uptrend. Either way, it’s worth remembering that everything in the markets is cyclical—from asset class returns to economic growth to long-term currency fluctuations.

This article originally appeared at Fortune. Reprinted here with permission.