Diversification has been a drag on investor portfolios for a number of years now.

In a world where one asset class (U.S. large-cap growth stocks in this instance) is far and away the best performer, diversifying into other asset classes or strategies will make you feel silly.

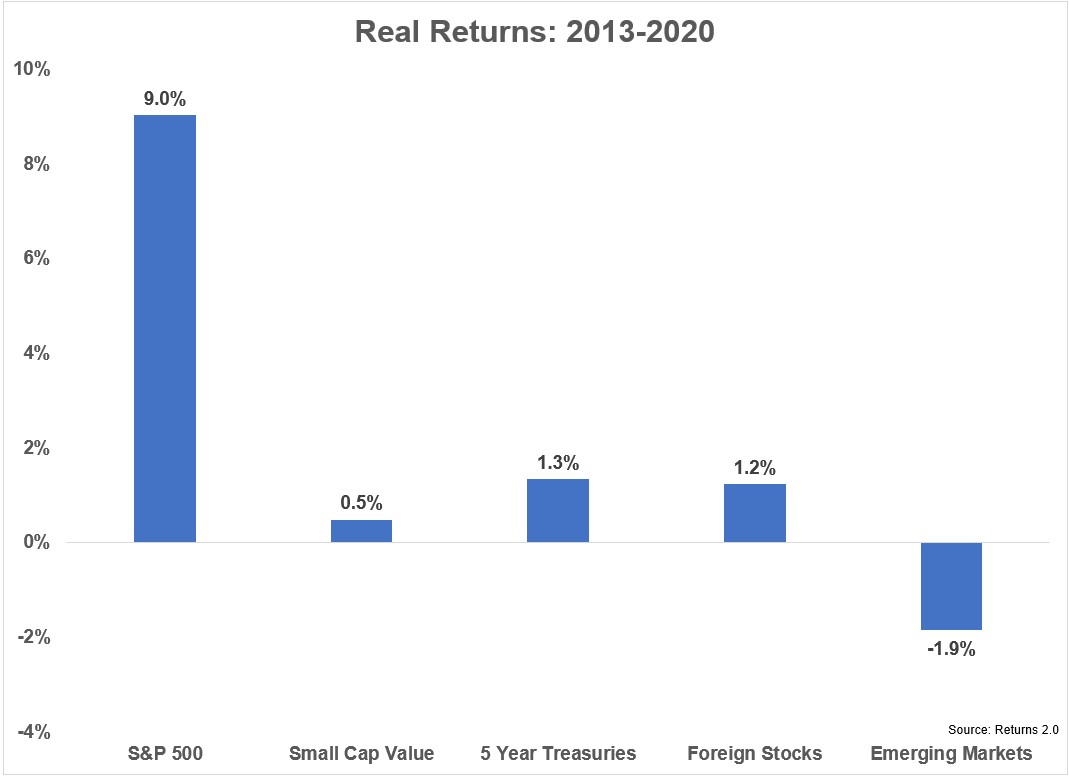

These are the annual real returns (after inflation) for the S&P 500 and a handful of other asset classes since 2013:

Allocating away from the biggest U.S. stocks has been painful, leading to the inevitable ‘Why would you ever invest in anything else?’ question.

It’s a legitimate question. Maybe the biggest stocks in the world will continue to dominate. Maybe software will eat the rest of the stock market. Maybe things really have changed and diversification among asset classes is pointless.

This isn’t the first time the S&P 500 crushed these other asset classes (and it won’t likely be the last).

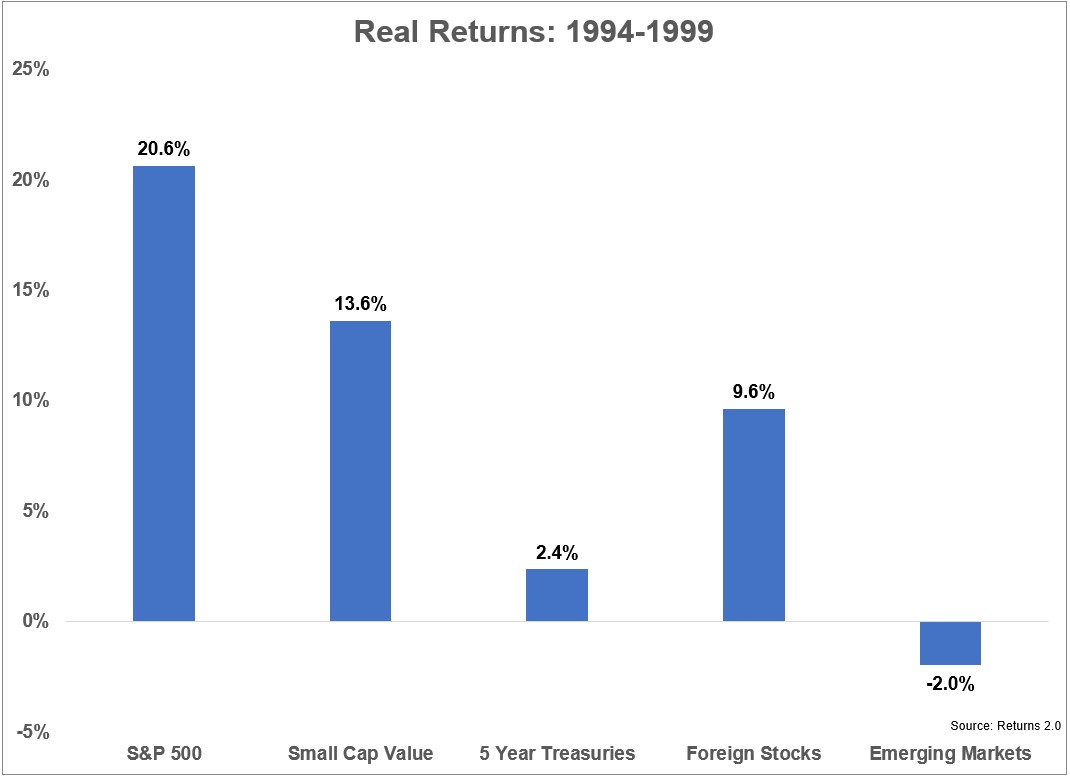

Although the absolute returns weren’t nearly as bleak in small caps and foreign stocks, the relative outperformance of the S&P was fairly similar in the mid-to-late 1990s:

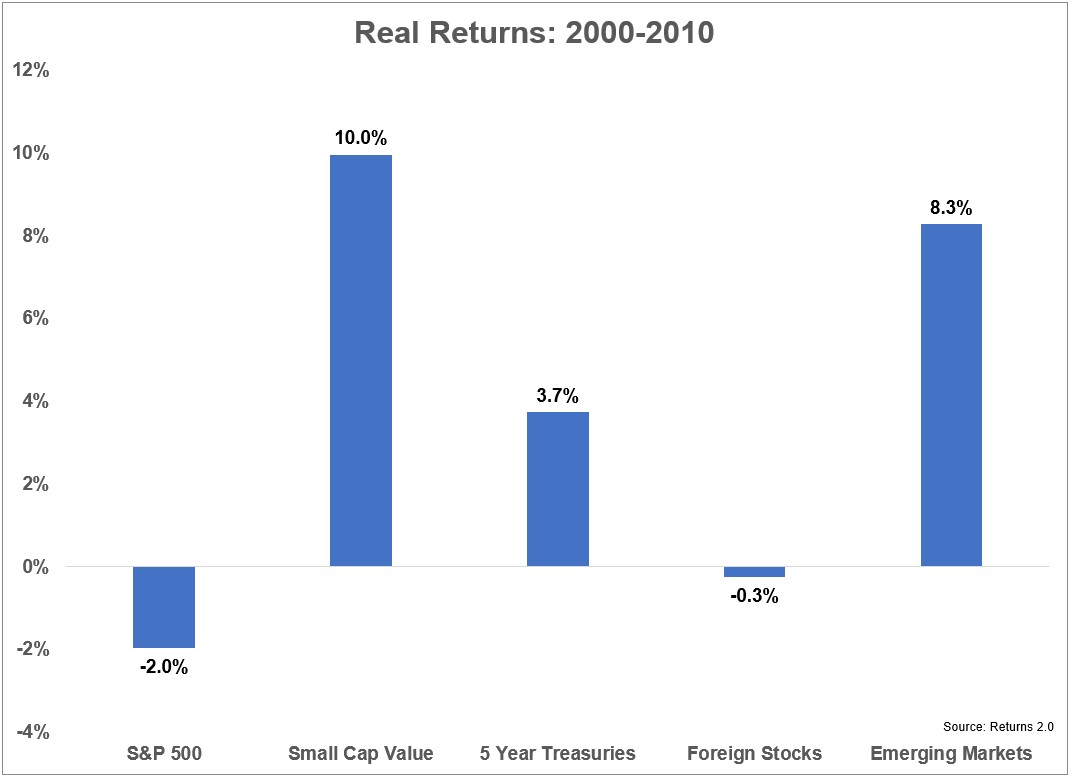

This was the “New Economy” where tech stocks also featured prominently. The cycle following this period is one of the main reasons so many investors ventured outside of large-cap U.S. stocks for diversification benefits:

The first part of this century was quite unkind to the S&P 500 (and foreign developed stocks) while small caps, bonds and emerging markets picked up the slack.

Markets are always and forever cyclical but it always feels like the current iteration will be the one to end all cycles.

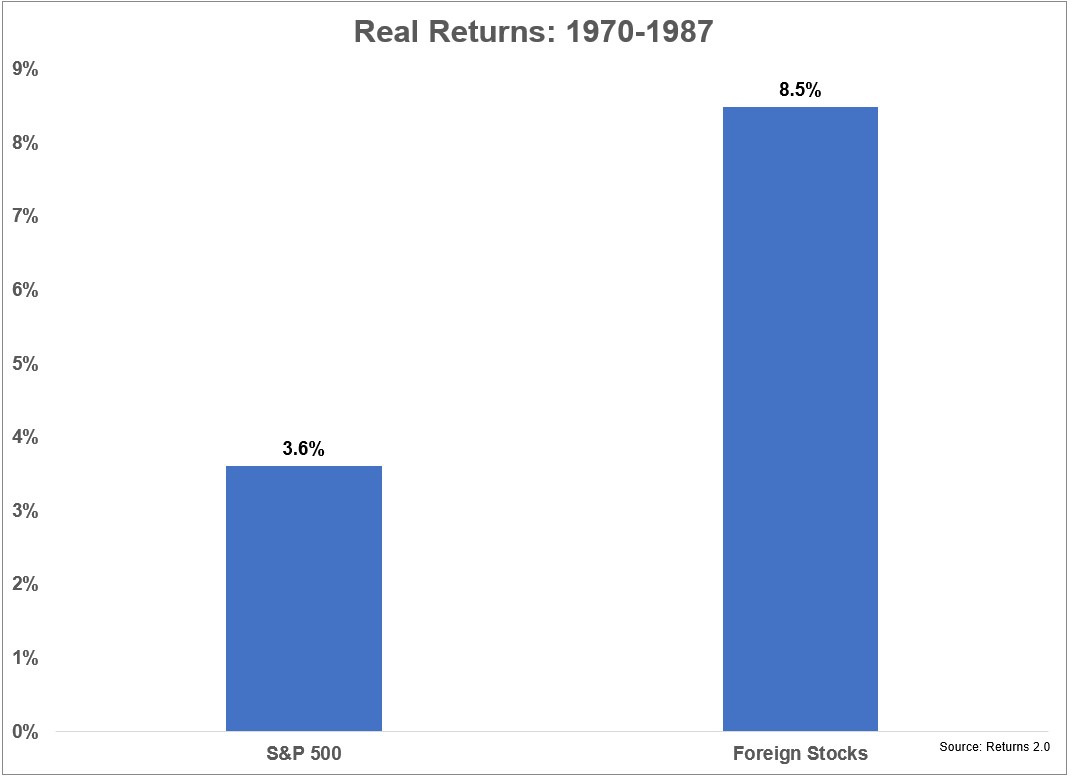

Foreign stocks had their time in the sun during the 1970s and 1980s as the MSCI EAFE more than doubled up the annual real returns on the S&P from 1970-1987:

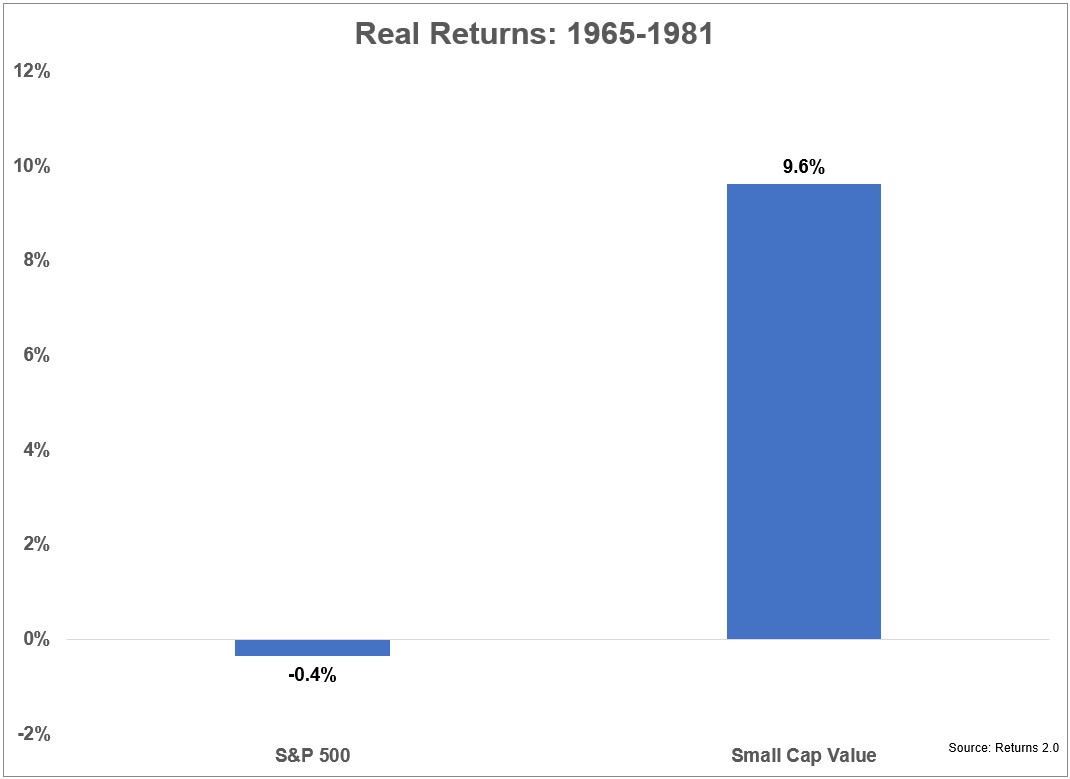

The sideways market from 1965 through 1981 caused by out of control inflation saw annual real returns of -0.4% for the S&P 500. That’s a 17-year stretch of negative returns after inflation (which was the primary cause for these dreadful returns).

Small cap value stocks were up nearly 10% annually on a real basis over the same time frame:

I could go through countless other examples showing any number of asset classes ruling the day or bringing up the caboose. This is the nature of investing. The best way to win any argument about an asset class or investment strategy is to change the start and end dates.

Did I cherry-pick these dates and asset classes?

Sure. But the numbers are the numbers.

Will these asset classes assure investors that they’re widely diversified over any type of market environment?

No, there are plenty of other asset classes and investment strategies to choose from.

The point I’m trying to make here is that the S&P 500 is not a foolproof investment strategy. Nothing is.

There are going to be times when the S&P experiences dreadful relative and absolute underperformance to gold or trend-following or value or international stocks or any other asset class or investment structure you can think of.

It may not feel like it now but eventually something else will outperform. When that happens the reasons will look obvious in hindsight.

I’ve never looked at diversification through the lens of Harry Markowitz and Modern Portfolio Theory. Diversification is more about admitting to yourself that you have no idea which asset class or strategy will do the best in the future.

Could you get lucky and have your entire portfolio in the best-performing sector, strategy or asset class during an opportune window for your assets?

Anything is possible.

The problem with investing is luck and timing have more to do with your success and ending balance than most investors are willing to admit.

All of the investment legends we worship have enviable qualities such as the right temperament, brains and the ability to make wise decisions with imperfect information about the future. But many of them were also in the right place at the right time when they began investing.

Successful investing and good luck are more synonymous than you think.

We’re currently in our third major crisis over the past 20 years and markets have arguably never been harder to beat. There are more ultra-intelligent investors in today’s markets than ever yet really no new Warren Buffett or George Soros to come up through the ranks.

There’s probably not a single star fund manager under the age of 50 right now.

There are many nuanced reasons for this but one of the simplest explanations is bad luck. If you entered the professional money management industry over the past 20-25 years, you simply had bad timing.

They don’t teach you in business school that the key to a successful career in asset management is to enter it in the early-1980s when interest rates are in the double-digits and stock market valuations are in the single digits.

This is all a long-winded way of saying you have to account for luck in the investment process. No one can prepare for good luck but there are ways to manage bad luck.

Diversification is one of the best tools available to avoid allowing bad luck to give you extreme outcomes at the worst times.

Further Reading:

The 5 Types of Investors in this Market

*The other asset classes here were proxied using the Fama-French Small Cap Value Index, MSCI EAFE and MSCI Emerging Markets Index.