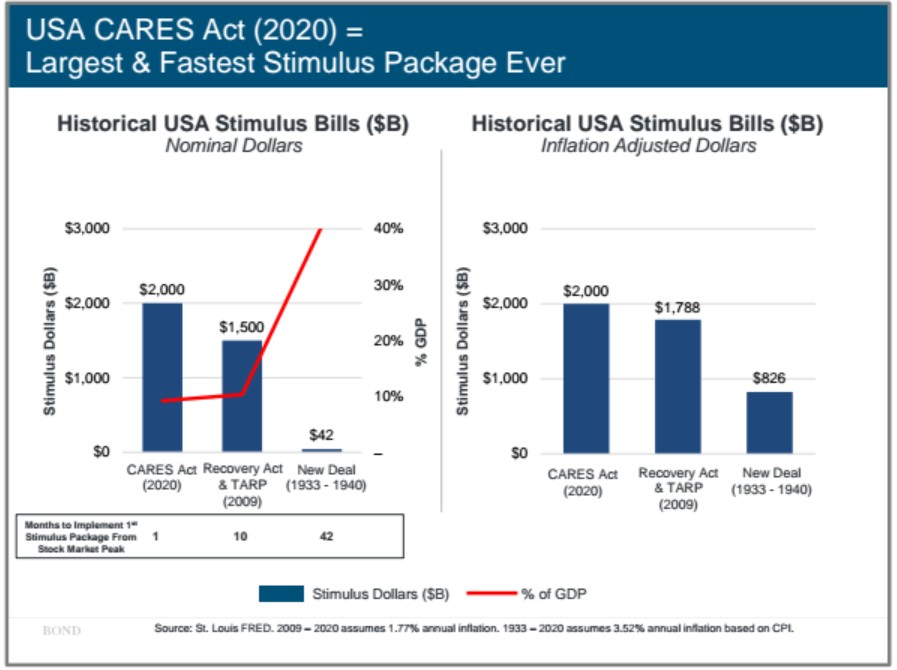

At the end of March, the federal government passed the $2.2 trillion CARES Act to provide financial relief to millions of Americans and a number of businesses to help see them through the crisis. This week they just tacked on an additional $484 billion.

That’s around 10% of annual economic output in the U.S.

This chart from Mary Meeker shows this is the largest and fasted stimulus rescue package ever (and this was before this week’s additional funding):

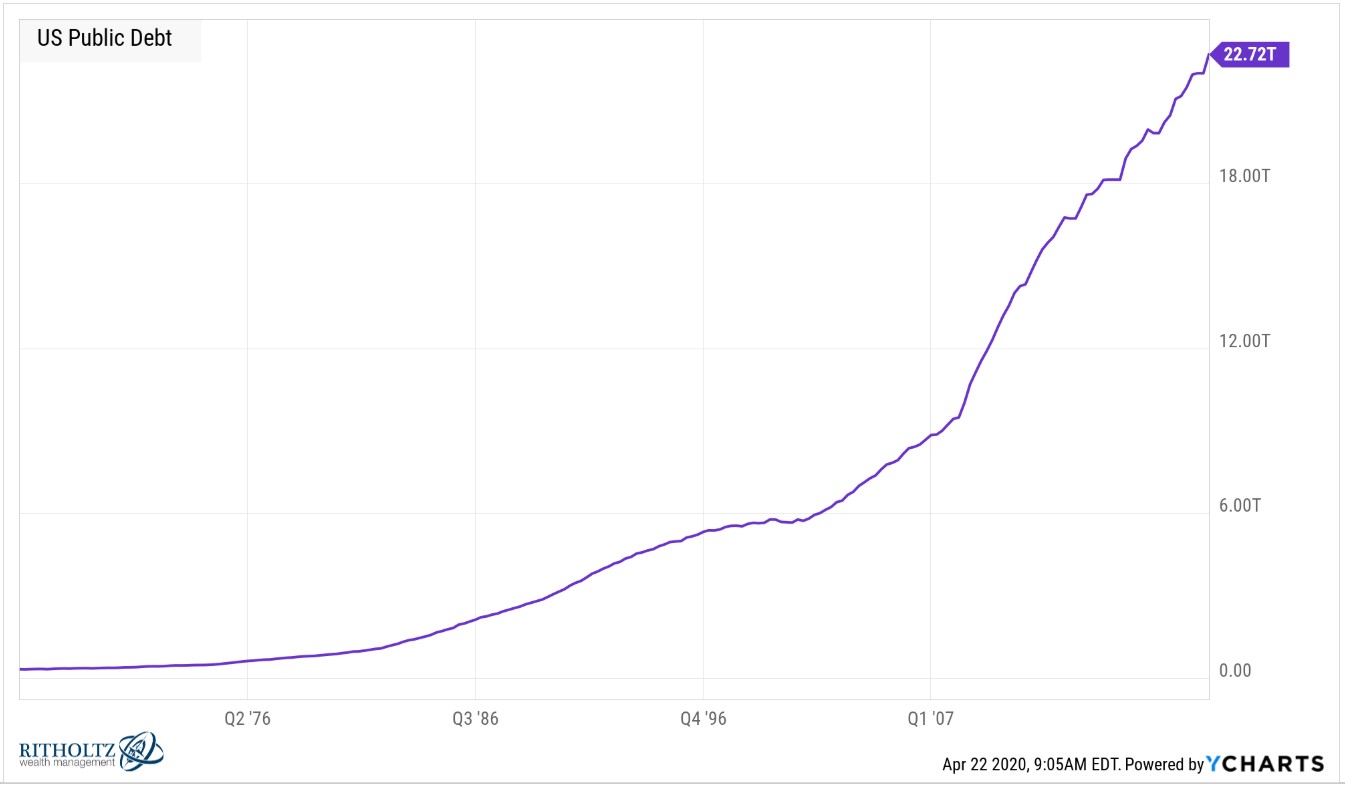

A number of people were already concerned about government debt before this crisis hit:

So we’ve tacked on even more since the end of 2019.

Is this debt so unsustainable it’s going to wreck future generations and leave them holding the bag?

Are we really screwing the grandkids?

The debt numbers by themselves look scary but they need to be placed in context to give them some meaning.

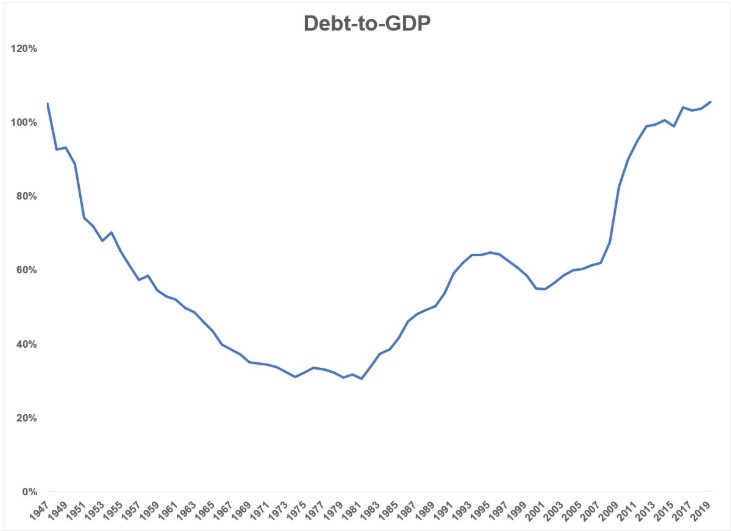

Here is debt-to-GDP before this year’s additional $2 trillion+ in spending:

The problem with the current crisis is this number is going to rise one way or another: (1) debt rises or (2) GDP falls or some combination of (1) and (2).

Since the economy is on the shelf for the time being that means if debt doesn’t rise to help out individuals and businesses, GDP will fall even more. So one way or another, debt-to-GDP is rising because of this crisis.

It all depends on the levers we pull in terms of the numerator or the denominator (and so far we’ve chosen to increase the numerator to help offset the denominator).

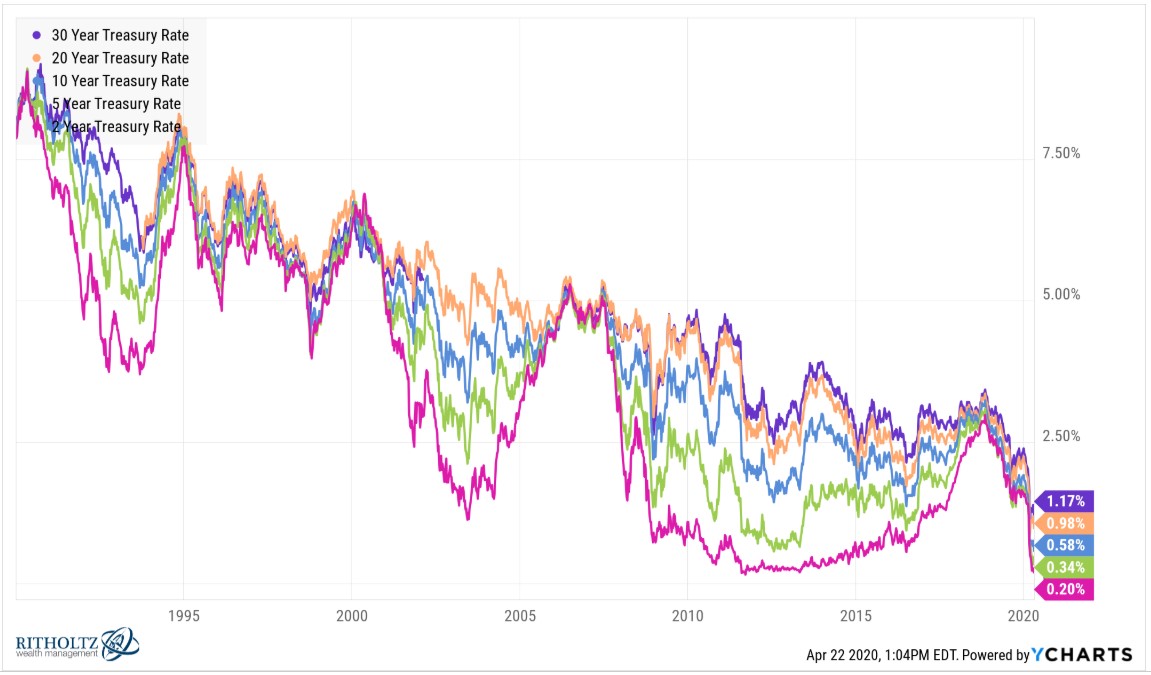

Although absolute debt heading into this crisis was high, you could argue we’ve never been in a better position to add debt to the country’s balance sheet.

Just look at our current borrowing costs:

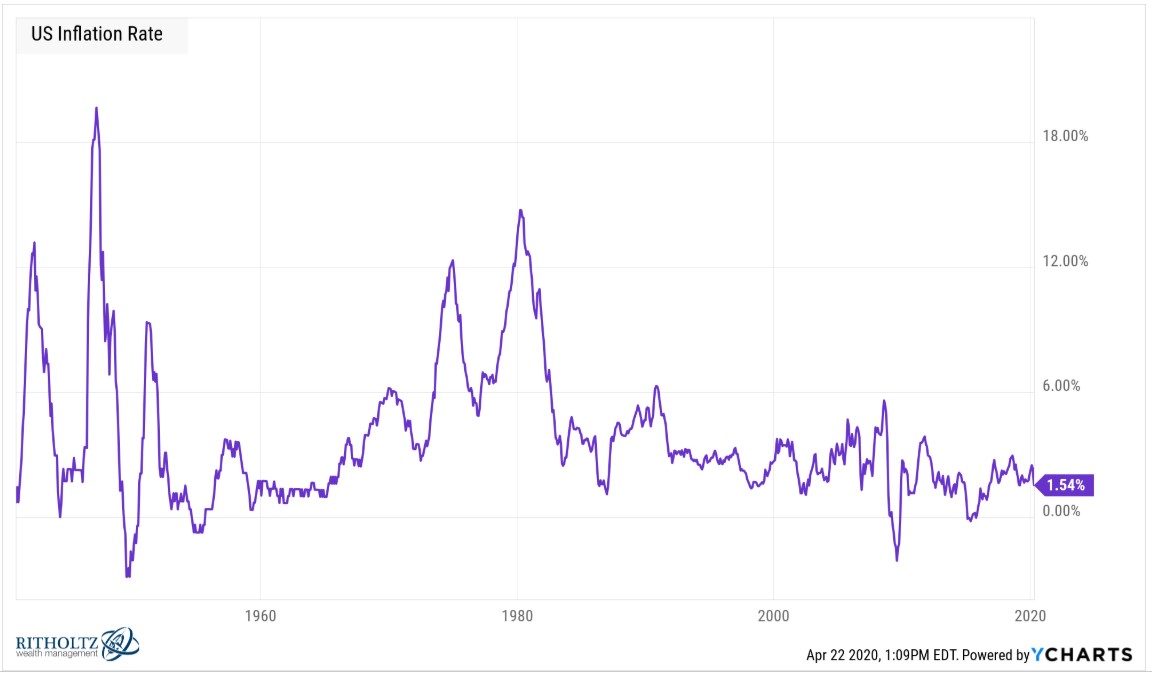

And the inflation rate:

Generationally low interest rates and subdued inflation make for a perfect opportunity to add debt during this type of crisis.

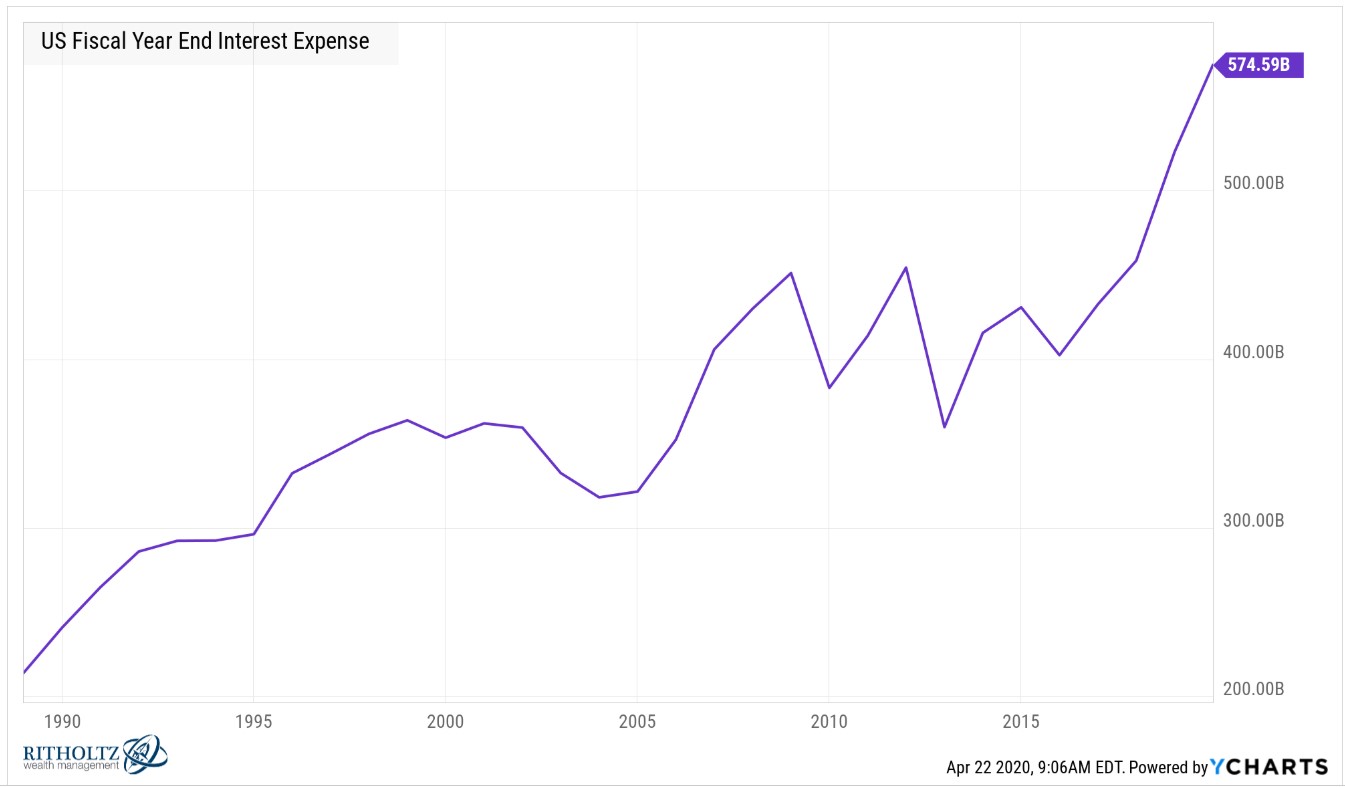

It’s not only the debt itself that matters but our ability to service that debt. As debt has risen so too have interest expenses:

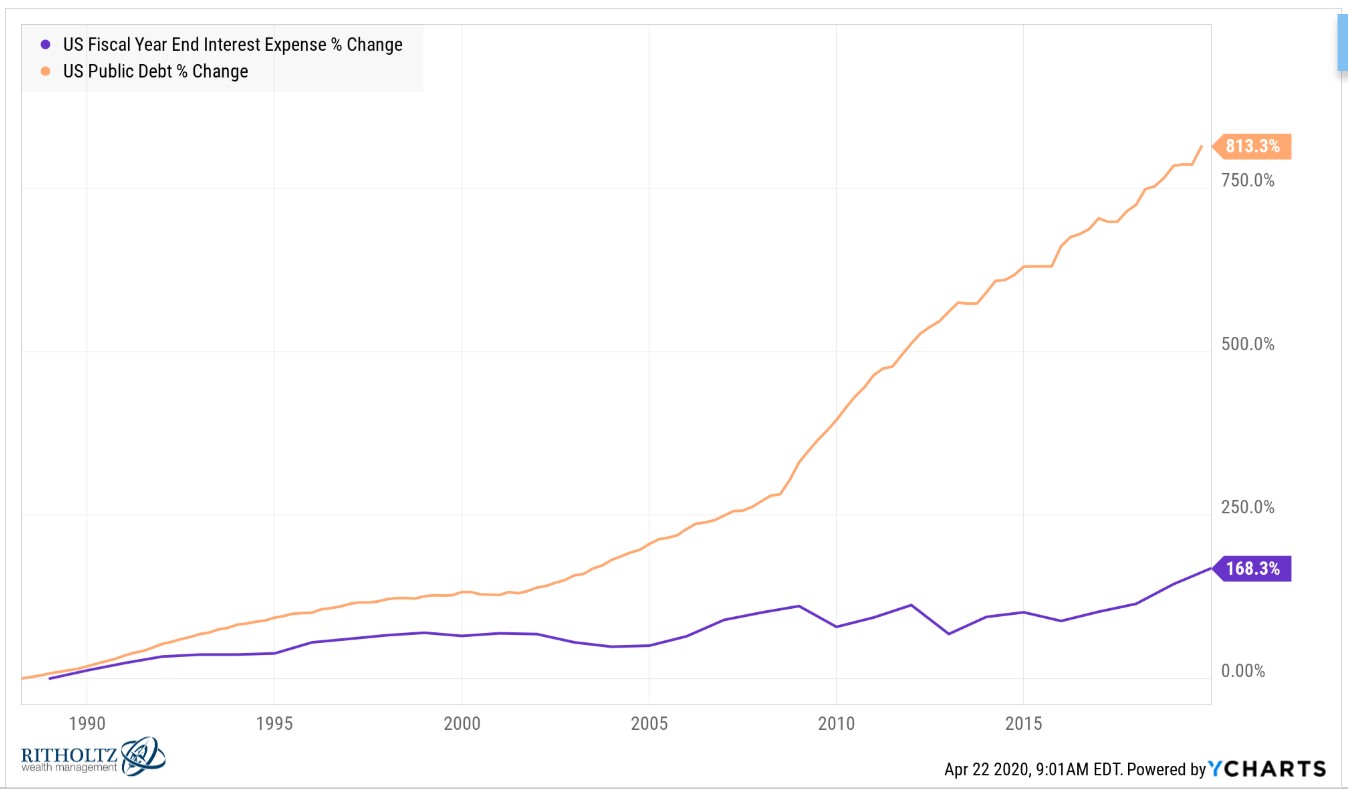

But the growth in debt has far outpaced the growth in interest expenses since the early-1990s:

Rates are so low at the moment this divergence in the rate of change is sure to get wider.

For every $1 trillion we borrow at prevailing 30 year treasury yields, the interest expense is just $11.7 billion a year. At 10 year yields, the annual interest rate expense is just $5.8 billion per $1 trillion. These numbers are rounding errors in an economy this big.

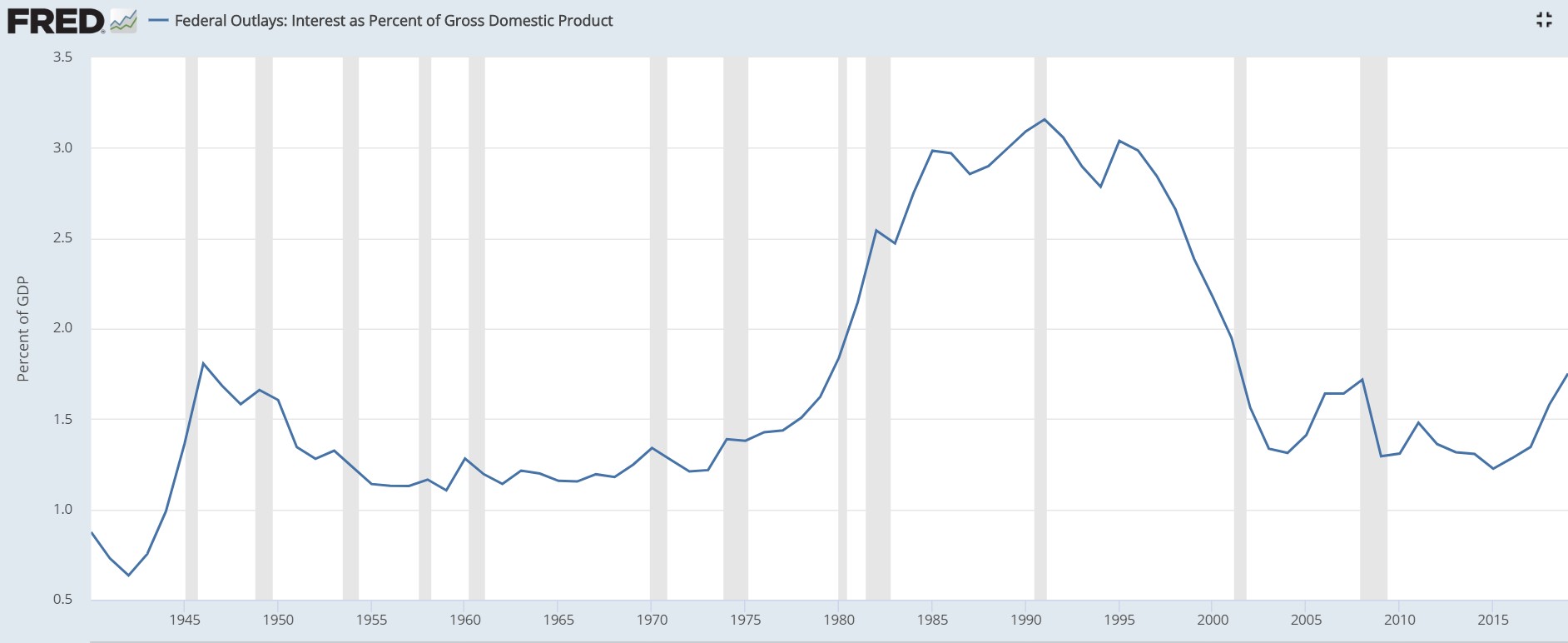

Looking at these numbers going back even further you can see interest was actually a bigger expense in the 1980s and 1990s because borrowing costs were so much higher:

The last time debt-to-GDP was at current levels was WWII when it got as high at 120% or so following the war. On the inflation chart above you can see a huge spike in the post-WWII years which helped with some of that debt.

Inflation is one way out of this debt as the purchasing power of the money you’re paying back on the debt gets lower over time. This is the reason inflation is the biggest risk to bondholders over time.

If we have to worry about inflation in a few years I view that as a good problem to have because it means we beat this thing and people are out spending money again and wages are rising.

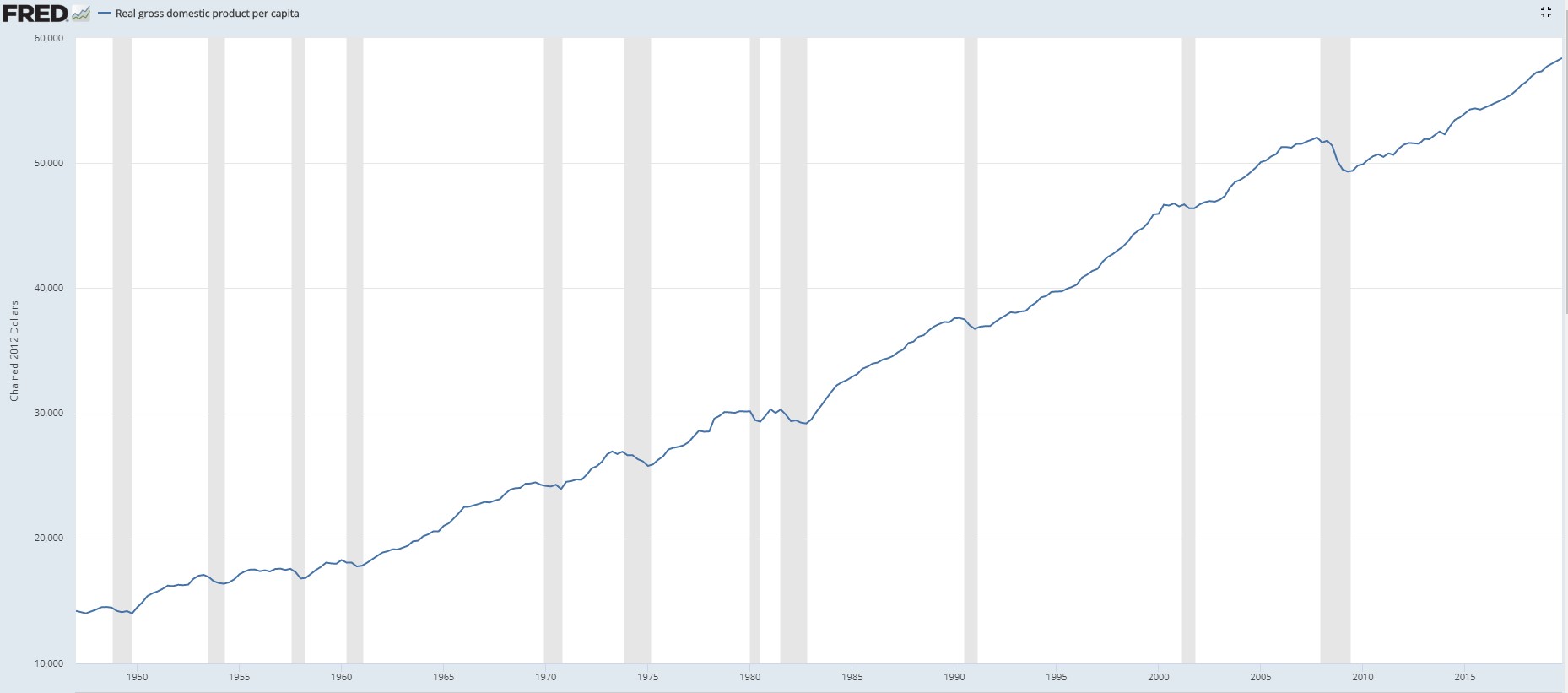

The second way out of debt is simply growing the economy, something we have been very good at over the long haul:

Of course, we’re never going to “get out of debt” in the traditional sense. The government doesn’t have to pay it off. Government debt doesn’t get retired as much as rolled over. And as long as the economy continues to grow in the future you can expect the debt to grow as well.

The government is not a household. They have the ability to collect taxes. They also own a ton of assets that people who complain about debt fail to mention. And because the dollar is the global reserve currency and we control that currency, we can literally create money out of thin air. I haven’t found too many households that operate under similar conditions.

It’s important to remember that all of that debt is also an asset for someone else. If your bond funds hold U.S. treasuries, you are a lender to the United States government and receive interest payments because of it. One organization or country’s debt is another investor’s income.

In fact, debt is one of the main engines for growth for governments, businesses and individuals alike because it gives you the resources to do things today that can allow you to provide even more resources in the future.

Is there a point where the country’s debt becomes untenable and a real problem? That could certainly be the case if all of our spending provides no boost to the economy or somehow people lose faith in the system.

That loss of faith would likely be accompanied by higher interest rates and thus higher inflation.

One thing is for sure — now is NOT the time to worry about our country’s debt.

Interest rates are lower than they’ve ever been. Inflation isn’t a problem. The economy has its parking brake on.

If anything, the government should be spending more money at the moment to keep the economic machine running to account for the pain individuals and businesses are experiencing because of the virus.

The government slowing their spending right now is probably the biggest risk the economy and markets face until we can get things back to normal.

Further Reading:

When Does the Federal Deficit Matter?