At the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, a man named Clark Stanley got up on stage dressed as a cowboy, reached into a bag filled with rattlesnakes, slit one open in front of the crowd and put the snake in the pot of boiling water.

The fat that rose to the top of the boiling pot was scraped off, bottled up, and sold for its magical healing power.

Of course, snake oil has no healing power but people back then didn’t know that.

In my new book, I wrote a chapter about a charlatan posing as a doctor who sold fake treatments to people who were desperate to get better and had no one else to turn to. What surprised me most from my research is how primitive the medical profession was in the late-1800s and early-1900s.

Medical school was basically a joke until the early 20th century. Most would accept anyone who was willing to pay tuition. Only around 1 in 5 medical students were even required to have a high school diploma to get in. Just one medical school in the entire country required a college degree to get in.

John Brinkley, the quack I profiled in my book, paid $100 for a diploma instead of actually finishing medical school. The American Medical Association (AMA) was founded in 1847 to provide some regulations and guidelines for physicians, but it took them decades to gain enough power to enact them.

One of the reasons the profession was such a mess is the treatments and technology available at the time were so lacking.

Until 1846, all surgeries were performed without the help of anesthesia. They gave people alcohol or cocaine to ease the pain.

In 1836, Nathan Rothchild was one of the richest people in the world, the Jeff Bezos of his day. He died at the age of 58 from a minor infection that could have been cleared up with a simple antibiotic a hundred years later.

Calvin Coolidge was the 30th president of the United States from 1923-1929. Coolidge’s son died at 16 in 1924 from an infected blister on his foot because there weren’t antibiotics available to take care of the infection.

In his new book Fewer, Richer, Greener, Laurence Siegel makes the case that there have been two important events that have shaped human progress over the past 200+ years. The first was the industrial revolution, which more or less kicked off the current period of modern economic growth, where before basically none really existed for all of human history.

The second most important event was reported in the New York Times in March 1942:

Anne Sheafe Miller . . . was near death at New Haven Hospital suffering from a streptococcal infection. . . . She had been hospitalized for a month, often delirious with her temperature spiking to nearly 107, while doctors tried everything available, including sulfa drugs, blood transfusions and surgery. All failed. As she slipped in and out of consciousness, her desperate doctors obtained a tiny amount of what was still an obscure, experimental drug and injected her with it. “Within about a day,” writes Lily Rothman in Time, “her temperature was back to normal. Miller was cured.”

Thanks to this first clinical use of penicillin, Anne Miller lived for 57 more years, enjoyed a productive life as a nurse and the wife of a school headmaster, and died in 1999 at the age of 90.

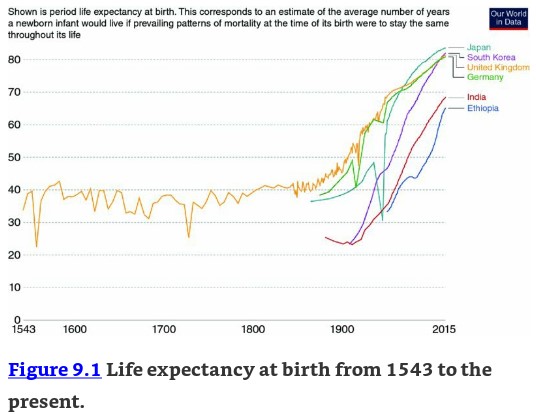

Siegel shows that despite income gains, higher economic growth, and technological innovation in the UK, there was no meaningful change in life expectancy from the 1540s through the 1850s:

The development of penicillin improved this situation drastically but it was also simple things that we now take for granted that caused this number to finally move in the right direction.

Technological breakthroughs and a more modern economy pushed society forward by leaps and bounds but it was something as simple as washing your hands and keeping drinking water clean that finally increased life expectancy for the entire population.

In the 1850s, Dr. John Snow came to the realization that lives could be saved by keeping sewage out of the water supply (which would cut down on fatal diseases such as cholera).

Around this same time, a Hungarian physician named Ignaz Semmelweis noticed an enormous discrepancy in mortality rates for new mothers during childbirth in the two maternity wards in his hospital. While working at a hospital in Vienna, Semmelweis realized the doctors’ maternity ward had three times the mortality rate as the midwives’ maternity ward.

Physicians and medical students were experimenting on cadavers in the morgue during their downtime while the midwives were not. The doctors and students weren’t washing their hands, thus transferring all sorts of germs and diseases to the new mothers.

Semmelweis was initially ridiculed by the medical community because this flew in the face of established opinions held at the time. But eventually he was proven right. Once doctors learned the importance of washing their hands this improved life expectancy for new mothers dramatically.

Siegel estimates there is now a greater proportion of 20-year-old Americans who have a living grandmother than had a living mother in the year 1900.

Something as simple as washing your hands when interacting with hospital patients may seem obvious now but this is still something that can be improved upon, especially in light of the outbreak of coronavirus.

A recent MIT study estimates only 70% of people wash their hands after going to the bathroom. And 50% of those people aren’t doing it right. They further estimate that just 1 in 5 airport travelers has clean hands.

If we were able to simply bump that number up from 20% of travelers to 60%, that could potentially slow the spread of disease by nearly 70%. Even 30% of travelers with cleaner hands could reduce the impact of a disease by nearly one-quarter.

This is a good reminder that advice doesn’t have to be complicated to be effective.

Source:

Fewer, Richer, Greener: Prospects for Humanity in an Age of Abundance

Further Reading:

Fear and Influenza: How Viruses Spread