“It was as if the virus were a hunter. It was hunting mankind. It found man in the cities easily, but it was not satisfied. It followed him into towns, then villages, then individual homes. It searched for him in the most distant corners of the earth. It hunted him in the forests, tracked him into jungles, pursued him onto the ice.” – John Barry

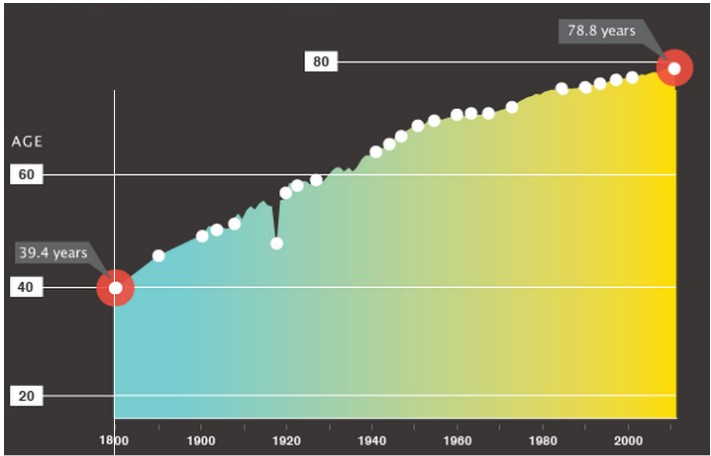

If you look at the long-term life expectancy chart for the United States the general trend has been moving higher over the past 200+ years:

Except there’s a noticeable dip in the early-1900s. The influenza epidemic that exploded onto the scene in 1918 killed enough people to depress the average life expectancy in the U.S. by more than 10 years.

The statistics caused by the spread of that virus are unfathomable:

- Experts believe nearly 700,000 people died in the United States because of what is now known as the Spanish Flu. In terms of today’s population, that would mean close to 2 million deaths.

- Epidemiologists today estimate influenza caused somewhere in the range of 50 to 100 million deaths worldwide. This was roughly 5% of the entire world population in 1918.

- Influenza typically kills the elderly and infants but the 1918 version saw roughly half the death total fall to young people in the prime their lives, in their 20s and 30s.

- It’s estimated as many at 8-10% of all young adults living at the time may have been wiped out by the flu.

- The virus was so lethal, two-thirds of all deaths occurred within a period of 24 weeks.

- India was by far the country most impacted by the disease. Upwards of 20 million people died.

- So many people were dying, funeral homes ran out of caskets and hospitals ran out of beds and physicians to treat people. Bodies were piled up on the streets in many cities.

- In less than two years, influenza killed more people than the Black Death took out during a century in the 1300s.

The 1918 pandemic killed more people than any other disease in human history. You don’t hear much about it for a couple of reasons.

First of all, there wasn’t much written about it firsthand from those who lived through it. Most people wanted to forget about it. It also coincided with World War I, which is overshadows the flu outbreak from a historical perspective. World War I also helped spread the disease farther and wider than it may have gone otherwise.

While the 1918 influenza outbreak is commonly called the Spanish Flu (the papers in Spain gave it this name after a huge outbreak in the country), the virus was actually traced back to a small town in Kansas which was home to a military base. From there the flu spread from soldier to soldier and then traveled around the globe as those soldiers set sail for the war in other countries.

One of the reasons the 1918 epidemic hurt so many communities so badly is because the nation’s resources were being diverted to the war. Doctors, nurses, and medical supplies were needed for the war.

For most people, the flu is nothing more than an inconvenience but it’s far more deadly than I realized. The CDC estimates since 2010 there have been anywhere from 140,000 to 810,000 annual hospitalizations from the flu with a further 12,000 to 61,000 deaths caused per year.

Influenza itself is far scarier than you realize once you hear the medical description of it. John Barry paints the picture in his entertaining yet terrifying book The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History:

Regardless of where it began, to understand what happened next, one must first understand viruses and the concept of the mutant swarm. Viruses are themselves an enigma that exist on the edges of life. They are not simply small bacteria. Bacteria consist of only one cell, but they are fully alive. Each has a metabolism, requires food, produces waste, and reproduces by division. Viruses do not eat or burn oxygen for energy. They do not engage in any process that could be considered metabolic. They do not produce waste. They do not have sex. They make no side products, by accident or design. They do not even reproduce independently. They are less than a fully living organism but more than an inert collection of chemicals. Several theories of their origin exist, and these theories are not mutually exclusive. Evidence exists to support all of them, and different viruses may have developed in different ways.

Whatever the origin, a virus has only one function: to replicate itself. But unlike other life forms (if a virus is considered a life form), a virus does not even do that itself. It invades cells that have energy and then, like some alien puppet master, it subverts them, takes them over, forces them to make thousands, and in some cases hundreds of thousands, of new viruses. The power to do this lies in their genes.

But if viruses perform only one task, they are not simple. Nor are they primitive. Highly evolved, elegant in their focus, more efficient at what they do than any fully living being, they have become nearly perfect infectious organisms. And the influenza virus is among the most perfect of these perfect organisms.

Influenza sounds like the most horrifying movie villain of all-time.

The scariest part of the 1918 version of this ever-mutating virus is how it used the body’s immune system against itself when it went after young people:

The immune system changes with age. Young adults have the strongest immune system in the population, most capable of mounting a massive immune response. Normally that makes them the healthiest element of the population. Under certain conditions, however, that very strength becomes a weakness. In 1918 the immune systems of young adults mounted massive responses to the virus. That immune response filled the lungs with fluid and debris, making it impossible for the exchange of oxygen to take place. The immune response killed.

Because the virus is always changing and adapting, it’s impossible to predict how far it will go.

One of the hardest-hit cities in the U.S. towards the end of 1918 was Philadelphia. On October 5, 1918, 254 people died from the epidemic. The next day local papers quoted the health authorities who claimed, “The peak of the influenza epidemic has been reached.”

The very next day 289 Philadelphians died and the authorities again claimed the peak of the epidemic had been reached.

Over the next two days, more than 300 people would perish. Local leaders yet again told the public this was the high watermark in fatalities to assuage fear in the city.

The next day 428 people died.

For the next week or so the death toll would hit a new high each day. Nearly 4,600 people died during the week of October 16 in Philadelphia alone. This would turn out to be the peak but by this point, the citizens no longer believed what the experts, newspapers or local leaders were telling them.

They’d been witness to far too many lies and false promises at that point.

Although the flu lasted for well over a year, President Woodrow Wilson never once addressed the nation about the disease. In fact, the public heard nothing from their national leaders for fear of upsetting the mood in the country during a time of war.

While a number of doctors were doing their best to find a vaccine for the virus, it more or less petered out on its own. Barry describes what happened:

But the 1918 virus, like all influenza viruses, like all viruses that form mutant swarms, mutated rapidly. There is a mathematical concept called “reversion to the mean”; this states simply that an extreme event is likely to be followed by a less extreme event. This is not a law, only a probability. The 1918 virus stood at an extreme; any mutations were more likely to make it less lethal than more lethal. In general, that is what happened. So just as it seemed that the virus would bring civilization to its knees, would do what the plagues of the Middle Ages had done, would remake the world, the virus mutated toward its mean, toward the behavior of most influenza viruses. As time went on, it became less lethal.

Eventually, people who already survived the virus developed some immunity to it.

Not all influenza pandemics are lethal. Most people simply become sick and then recover.

No matter how deadly they end up, when a pandemic occurs, fear tends to spreads even faster than the virus itself. One of the reasons this is the case is because people are constantly looking for reassurance from those trying to predict the path of a virus that’s impossible to predict.

This is why it’s so difficult to handicap the range of outcomes for the coronavirus. There are far too many variables and the virus itself is a riddle wrapped up in an enigma.

You could try to quantify the supply chain problems or business slowdowns because of the virus but it’s impossible to gauge how far and wide fear will spread because of it. Influenza is inherently unpredictable but fear takes the shape of its own virus that infects us all.

This is why market downturns are so hard to predict. No one knows how to precisely model fear or lack thereof.

The good news is the markets and economy have their own form of reversion to the mean. Eventually things will get better.

The bad news is, much like a virus, there is no timetable for it to occur.

Source:

The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History