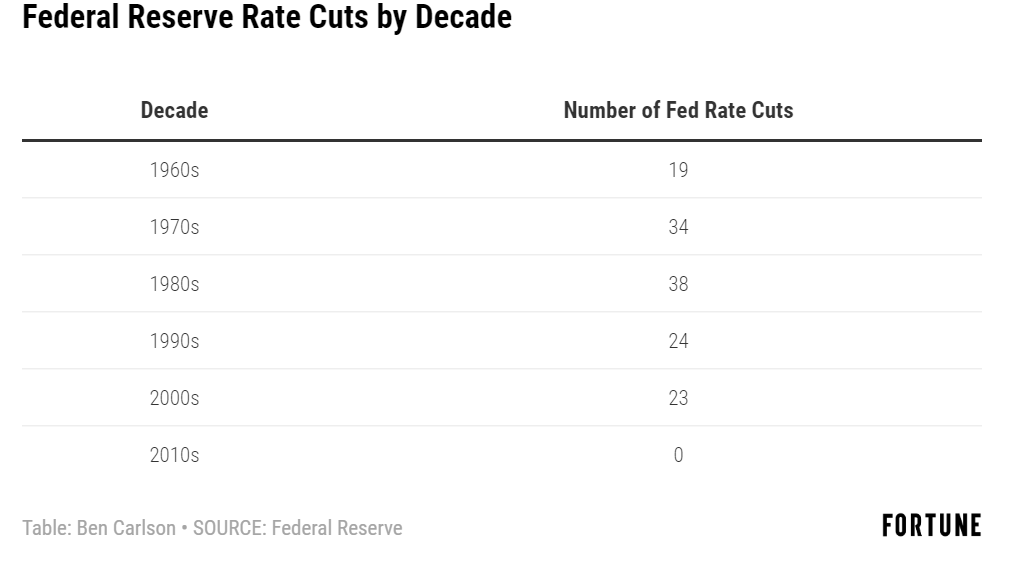

It’s possible the Fed will announce an interest rate cut this week. Surprisingly, it would be the first rate cut of this decade. In anticipation of this possibility, I went through all the Fed rate cuts going back to 1960 (as far back as the data goes that I could find) to see how unique the current scenario is from a historical perspective.

This is the piece I wrote for Fortune on my findings.

*******

Testifying before the House Financial Services Committee last week, Fed Chair Jerome Powell hinted that the Federal Reserve may cut short-term interest rates when they meet again later this month.

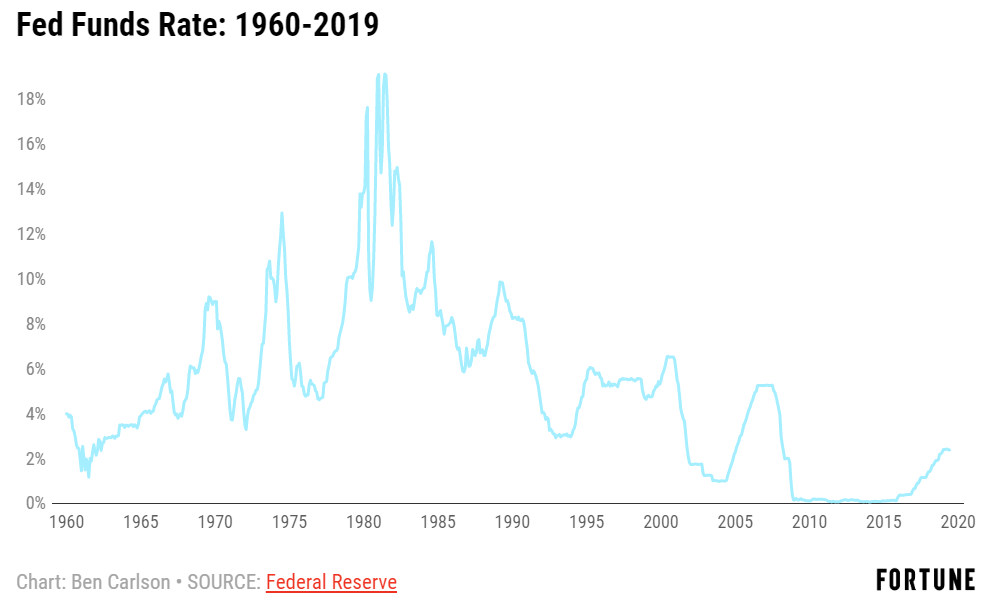

A rate cut wouldn’t be anything new in terms of history but it has been a long time since the Fed last lowered their short-term interest rate. Since 1960, the Federal Reserve has cut the Fed Funds Rate nearly 140 times. That’s good enough for roughly 23 times per decade. But there hasn’t been a single rate cut this decade:

Obviously, the biggest reason there hasn’t been a rate cut this decade is that rates were on the floor for so long following the Great Financial Crisis. Rates were effectively lowered to zero in December 2008 and didn’t rise from the dead until December 2015, when the Fed finally raised rates a quarter of a percent.

The average rate cut over the past 60 years or so is 50 basis points but there aren’t many historical scenarios that compare with the current market or economic situation. The Fed Funds rate currently stands at 2.5%. Before the financial crisis of 2007-2009, there have only been a handful of times where the Fed cut rates with yields below 3%.

More than 92% of all rate cuts since 1960 have come from higher levels of the Fed Funds Rate. Almost 99% have come when the unemployment rate was higher than the latest reading. And nearly 65% have come when the inflation rate is higher than it currently stands.

In response to a minor recession in 1960 which bled into early-1961, Fed Chair William McChesney Martin cut rates ten times while the Fed Funds Rate was below 3% over the course of two years or so (rates were also raised twice during this time). But the unemployment rate was much higher in those days because of the recession, topping out at more than 7% in 1961.

The current unemployment rate stands at just 3.7%, the lowest it’s been since 1969. In fact, the last time the Fed cut interest rates with the unemployment rate so low was in July of 1969, when they cut a quarter of a percent. But yields were much higher at that time as inflation was just beginning to take off heading into the 1970s. The Federal Funds Rate was nearly 9% during that rate cut in 1969 and the Fed would actually reverse course and raise rates the very next month in an effort to stave off inflation.

There was only one instance since 1960 where both the unemployment rate and the Fed Funds Rate were sub-4% when the Fed cut rates, which occurred in the summer of July 1967. That cut didn’t last for long as the Fed raised rates twice before the end of that year.

Inflation was fast approaching 6% heading into the 1970s and would reach double-digits by the end of that decade. The latest reading stood at just 1.6%. The only other time we’ve seen the Fed cut rates with inflation below 2% was during the early-1960s, but again that was in the midst of a recession.

So the current period is unique. Interest rates, unemployment, and inflation are all low by historical standards. And this would be the first rate cut in over a decade. Plus there’s the fact that stocks have once again been hitting all-time highs in recent weeks.

It’s quite possible the only reason the Fed began its hiking cycle in late-2015 is to give themselves the option to then cut rates yet again, which appears to be the current strategy. In the short-term, any Fed actions likely provide more of a psychological impact on the markets than a lasting change in fundamentals.

The short-term impact on the markets will always be driven by whichever story investors decide to latch onto. Some will assume a rate cut will signal a weakening economy. Others will assume the Fed will ease in time to keep the party going.

Eventually, those short-term narratives have to be backed up by long-term fundamentals or they run the risk of being outed as frauds. Even with nearly 140 rate cuts since 1960, there have been 30 double-digit stock market corrections and 8 recessions in the U.S. over that time. Regardless of what they do, the Fed can’t fight off recessions or bear markets forever.

This piece was originally published at Fortune. Re-posted here with permission.