Since going public in the summer of 2004, Google’s stock is up nearly 2000%.

That’s roughly 8x the return on the S&P 500 in that time.

It’s hard to imagine life without Google now that it’s so intertwined with everything we do in terms of using and gathering information.

I mean, how did people settle debates in the past without the ability to Google something? And remember having to stop and ask for directions before Google maps existed?

Google seems like an obvious home run with the benefit of hindsight but it wasn’t a foregone conclusion the company or the stock would be so successful. When I was in college we were forced to use search engines like Alta Vista, Yahoo! or AskJeeves.com when Google was still in its infancy.

None of these other search engines ever really gave you what you were looking for so we were forced to use actual books and periodicals to look stuff up. Talk about the digital Stone Age.

The day Google went public The New York Times wondered “whether the scrappy Internet search engine is really worth $27 billion” because of concerns about their dot-com bubble era line of thinking:

And unlike some of the dot-com-bubble darlings that famously turned to Wall Street to raise cash merely to burn it, Google is a profitable enterprise. But one worth more than $27 billion? Only time will tell if the company can fend off efforts by Yahoo and Microsoft to build superior search engines.

Google still exudes that unabashed Silicon Valley anti-establishment attitude, the kind that made 1999 such fun for a lot of young techies.

Even after they were public for a few years there were still plenty of doubters. Marianne Jennings wrote a book called The Seven Signs of Ethical Collapse which was published in 2006. Jennings does a nice job deconstructing the Enron, Worldcom, and Tyco debacles as a framework for spotting red flags in company management, financial statements, boards, corporate policies, and unethical behavior.

At the end of the book, she then uses that framework to predict companies and industries that could be in trouble in the future. One of the companies she chose is none other than Google.

And honestly the reasons make sense for where the company was at the time:

Their position of being innovators has carried with ith the accompanying earnings that defy gravity. And how does one top being a steady billionaire at that young age?

Sound economics dictate that continuing double- or triple-digit growth is not possible. Beware, those earnings are ad revenues, and there is room for accounting interpretation on booking ad revenues. Remember AOL’s debacle on its methodologies related to ad revenues. The SEC settled those issues for AOL despite its continuing claims of validity through the uniqueness of business. The patterns are easy to spot, and they do repeat.

Some of this could have stemmed from the fact that the dot-com blow-up and Enron fraud were still fresh in people’s minds. There was a natural skepticism of any results that looked too good to be true.

But even those inside some of these behemoth tech companies can’t always predict how these things will work out.

If you put $10,000 into Amazon at their IPO, you would either be one lucky SOB or a liar. It feels like Jeff Bezos could enter any business line or industry he wants and the incumbents would see their stock price get destroyed.

But let’s say you completely missed the first wave of Amazon’s success and instead waited until they decided to take over the world with their Prime membership program.

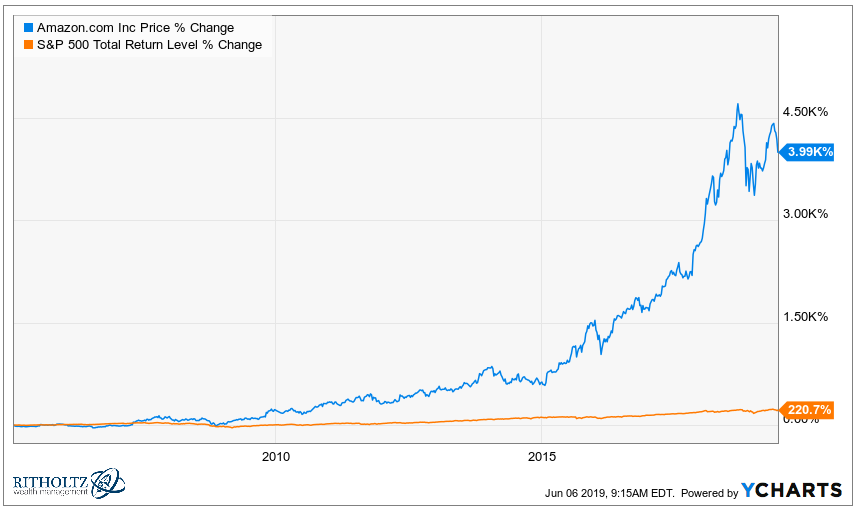

Since Prime was launched in early-2005, Amazon’s stock price is up nearly 4000%:

This one feels pretty easy in hindsight. I love Prime. Amazon is the first place I look for nearly anything we need to buy. Prime is the type of program I never knew I needed before but now would have a hard time living without it.

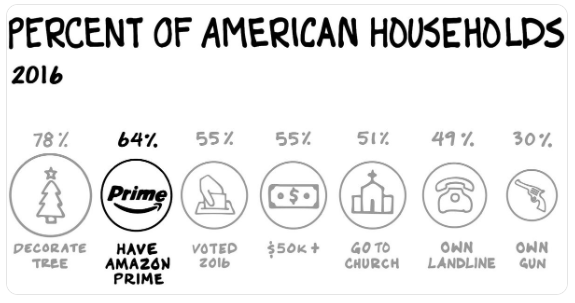

According to Scott Galloway, more Americans have a Prime membership than those who go to church or voted in the 2016 election:

But Prime wasn’t the slam dunk it seems when it was being rolled out. In fact, even the employees who were working on the program firsthand were skeptical at the time.

Jason Del Ray at Recode put together an insightful oral history about how Amazon created the Prime platform. Greg Greeley, the eventual VP of Amazon Prime, discussed some reservations people within the organization had at the time while they were building out the program:

Sometime in December I got this email from one of the engineers on the team saying, “Greg, we’re working so hard on this project and I look at it and as a [shareholder] I’m really scared. I think it’s going to take down the company. Are you sure the math works on this program?”

It was not obvious to even people that were writing the code that it was going to work in the long term.

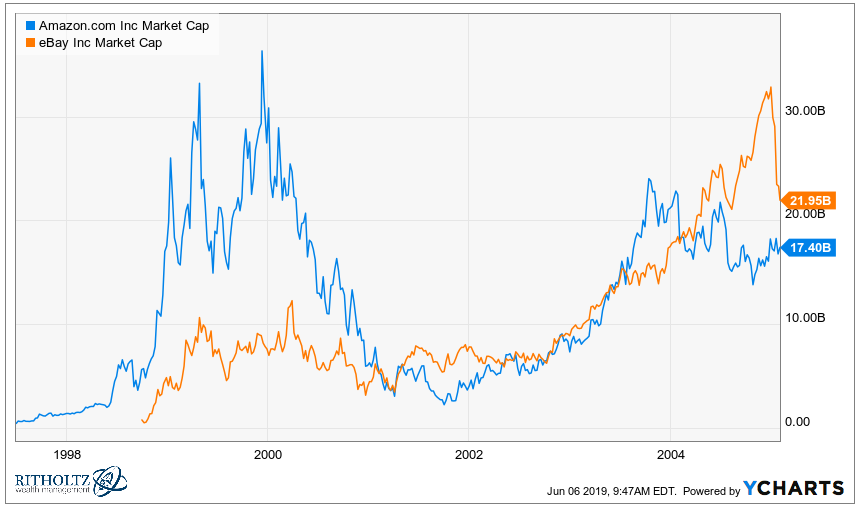

There were major concerns about the economics of a free shipping program. Amazon’s market cap was still smaller than eBay’s at the time and it wasn’t a foregone conclusion who the winner would be between the online selling platforms.

Prime isn’t the sole reason for Amazon’s success since then. AWS helped a lot and they’ve expanded into other market segments as well. But looking back at an Amazon stock price chart makes it seem like it was a foregone conclusion they were destined to be one of the largest companies in the world.

It’s rare to know which businesses or stocks are going to be successful in the moment. This is why back-tests are easy but front-tests are hard.

The past looks obvious but the future almost always looks messy.

Many good ideas are only known with the benefit of hindsight.

Further Reading:

The Unintended Consequences of Innovation