The New York Times had a piece last week about how the bond market is telling us something — panic, don’t bet on the Raptors, the GoT final season was actually good, worry:

Right now, all the action is in the bond market. It is sending powerful signals that there’s trouble ahead for the United States economy.

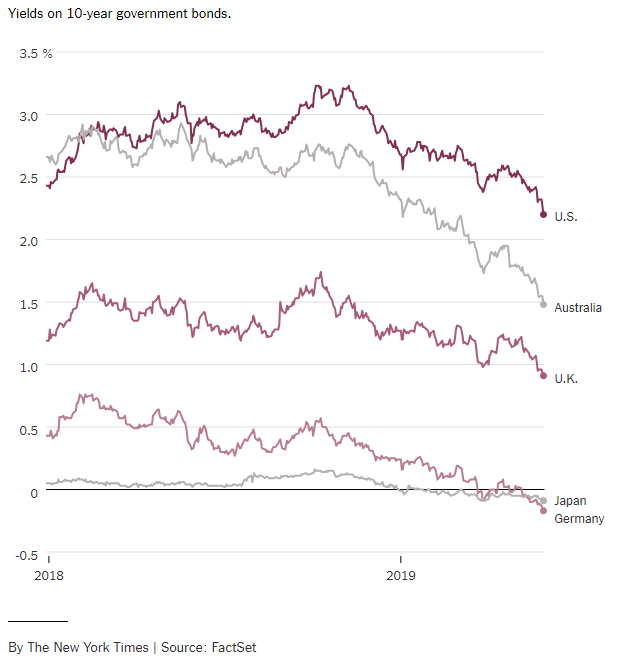

Yields are falling across the globe:

The idea here is that investors typically buy bonds, thus depressing rates from rising demand, when they get worried about the future.

These are yields on 10 year bonds, the rate most prognosticators typically pay attention to when discussing rates in general But there are plenty of other government bond maturities.

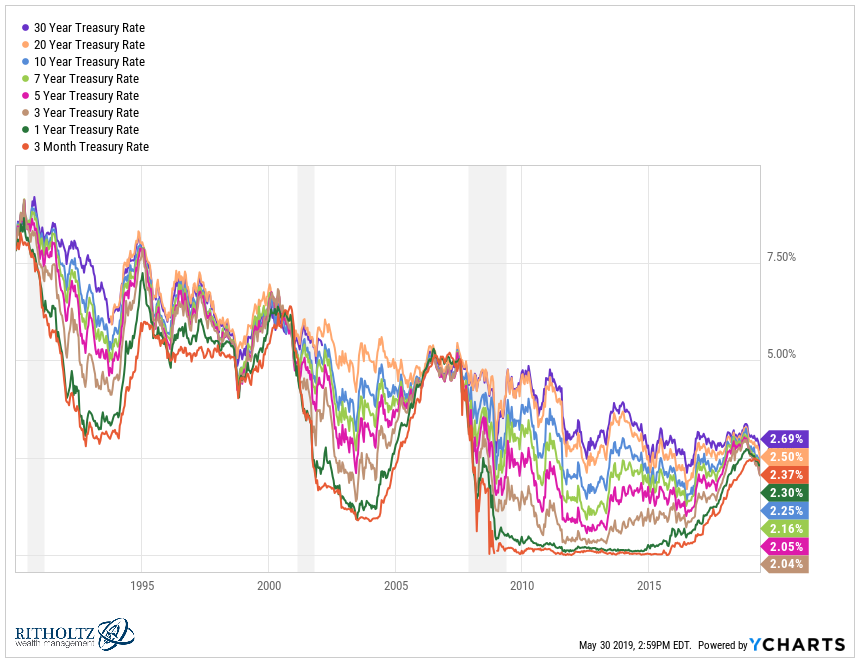

Here’s a look across a broad range of treasury yields in the United States going back to the 90s:

You can see the yield curve has compressed considerably in recent years as short-term rates have risen substantially while long-term rates haven’t budged much.

I’m having trouble squaring the fact that people seem to believe the bond market is smarter than every other market but it’s also manipulated.

I’ve been hearing for years that interest rates have been manipulated lower by the Federal Reserve.

The Fed has been buying bonds so you could make the case that they’ve certainly had an impact on the supply and demand of the securities and maturities they’ve been buying. And the Fed does control short-term rates.

But am I supposed to believe that these interest rates which have been manipulated are also screaming about the onset of a recession?

Which one is it: manipulated rates or the smartest assets in the room? Can it really be both at the same time?

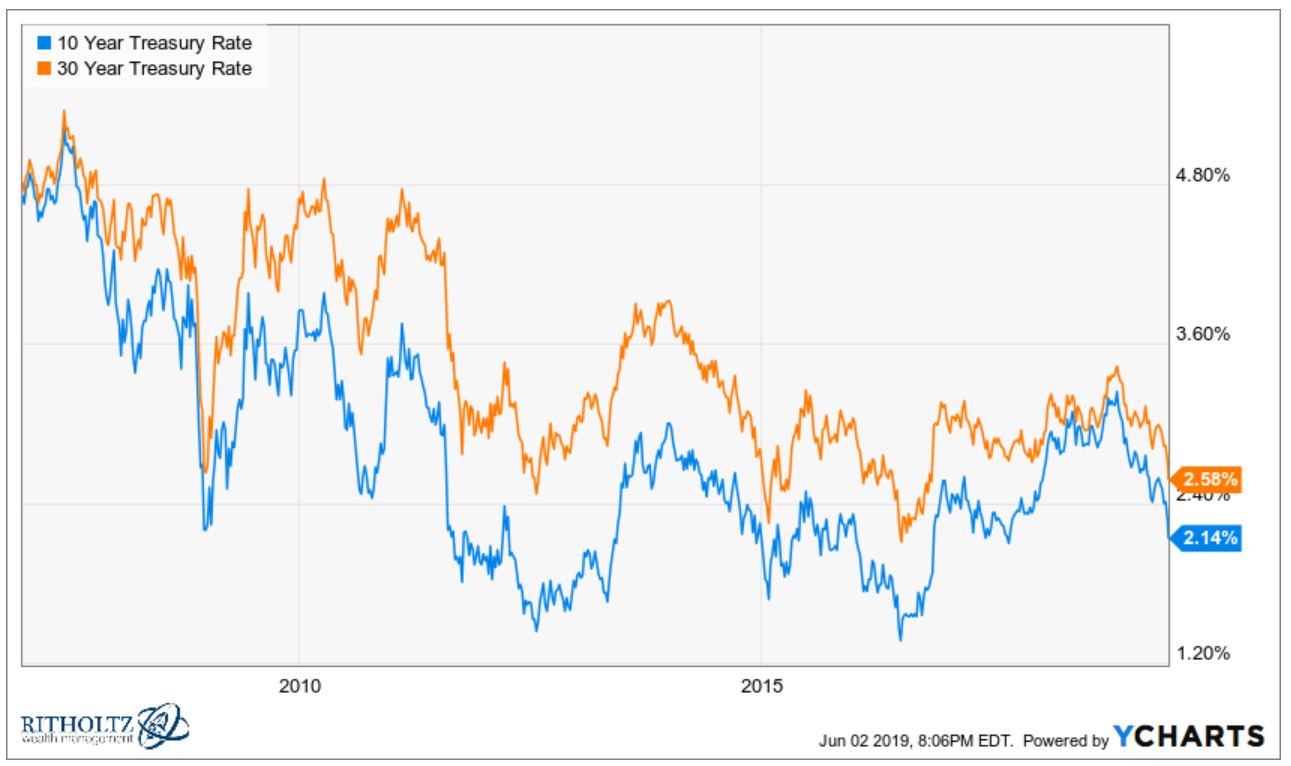

Here are the yields on the 30 year and 10 year treasury since the start of 2007:

The spread between the two bonds has risen and fallen on a number of occasions since before the Great Recession began.

And yields themselves have been all over the map, ranging from around 5% to well under 2%. Do these look like the moves of an asset that knows exactly what’s going to happen next for the economy?

The bond market is ginormous but it’s also constantly changing based on the amount of debt issued. For example, the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Bond Index, a proxy for broad U.S. bond market, had a weighting of roughly 19% to treasuries in 2007 (with the remaining allocation to mortgage-backed bonds, asset-backed bonds, and corporate bonds with some munies sprinkled in).

That number has now doubled so treasuries make up around 40% of the broad U.S. bond market. Sure the Fed controls rates to some degree but the supply and demand for these securities surely play a role as well.

Then there are inflation expectations, expectations for future Fed moves, expectations for the economy, and maybe some price/yield trends for good measure if you’re into that sort of thing.

It’s hard to argue each of these expectations could be lining up perfectly all at the same time but stranger things have happened.

I’m not going to argue with the yield curve. It has a compelling backtest as a predictor of recessions. It’s just that the timing is always the thing that will get you on these calls (my first piece about the possibility of an inverted yield curve was in the summer of 2016).

Maybe the bond market is trying to tell us something.

Maybe investors believe inflation won’t meaningfully transpire any time soon.

Maybe investors believe the Fed will cut rates.

Maybe the rest of the developed world is buying treasuries because their interest rates are so low.

Maybe investors are bidding up bond prices because people are still scarred from the last crisis.

Maybe predicting the future path of inflation and rates is harder than most people imagine.

Maybe the long end of the curve is smarter than the Fed.

But maybe not everything is a clear-cut signal about the economy.

Maybe sometimes the markets don’t make any sense even when it seems like they’re trying to tell you something.

Further Reading:

Arguing With the Yield Curve