Meet Sam.

Sam’s entire family has terrible luck when it comes to the timing of their retirement.

Sam’s great-grandparents retired at the end of 1928. Over the ensuing three years or so the stock market would drop close to 90% while the U.S. economy would contract nearly 30% in the Great Depression. In 1937, the stock market would be cut in half and a couple of years later World War II would commence.

Sam’s grandparents didn’t fare much better, retiring at the tail end of 1972. This was right before a brutal bear market which would see stocks cut in half from 1973 to 1974. The purchasing power of their portfolio would also be ravaged by inflation, which would run at a rate of 121% over the first 9 years of their retirement (more than 9.2%/year). From 1973 to 1981, the S&P 500 would lose 33% of its value in real terms.

Finally, Sam’s parents retired at the end of 1999, feeling pretty good about where they stood following the enormous tech-fueled bull market of the 1990s. In the first decade of their retirement, they would witness the U.S. stock market go down by half on two separate occasions with corresponding recessions in each instance. Over the first decade of their retirement, the S&P 500 would fall close to 10% in total.

Less than 20 years later, Sam is considering retiring early after catching the FIRE bug. Sam’s biggest worry is the possibility of retiring just before a market crash like the rest of her family.

Should Sam be worried? What if you retire just before a stock market peak?

Let’s run some numbers on Sam’s family tree to see how they would have fared in each of their scenarios.

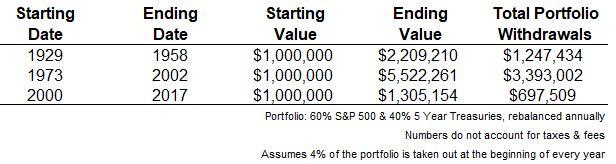

Sam’s family were all huge fans of balanced portfolios so we’re going to assume they all went into retirement with 60/40 portfolios consisting of 60% in U.S. stocks (S&P 500) and 40% in 5-year treasuries. They decided to take out 4% of the portfolio’s value at the start of each year for living expenses and do so for the remainder of their retirement (let’s call it 30 years for her great-grandparents and grandparents).1

Let’s also assume each of her family members retired with the equivalent of $1 million.2

So how did they fare?

Even retiring right around the peak of the market, their portfolios actually ended up in a good position in each case. Here’s what each one of these scenarios looked like:

You can see in each case the ending market value for the portfolio is higher than the original amount even after accounting for annual withdrawals.3 Obviously, the ending balances vary quite a bit because the 1973 start date benefitted from higher starting interest rates in bonds and the 1980s and 1990s bull market and the 2000 retirement is still a work in progress.

For these examples I used a simple 4% rule, taking out a flat 4% of the portfolio every single year regardless of the portfolio’s performance or the economic conditions at the time. One of the biggest risks in retirement is inflation because it impacts the purchasing power of your portfolio over time. During the Great Depression, the U.S. experienced deflation while I already mentioned the insane inflation of the 1970s.

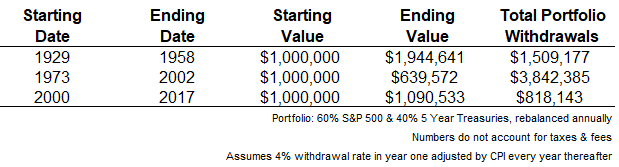

To account for this variable, I also ran the numbers by adjusting the withdrawal rate by the annual inflation rate every year.4 This should make things a little more realistic in terms of the spending rate. Here are those results:

You can see the ending balances aren’t drastically different in the 1929 or 2000 scenarios but inflation did take a monster bite out of the ending balance in the 1973 start date. This is because the spending rate was ramped up in the early years of retirement due to the inflationary environment.

Here are some takeaways from this exercise:

- Retiring just before a stock market peak could be ruinous to your financial health but it doesn’t have to be. A balanced portfolio was able to hold up using a simple set of assumptions even when our hypothetical investors were extremely unlucky with the timing of their retirement.

- Market volatility will likely lead to volatility in your portfolio’s ability to produce stable income during retirement. These are the trade-offs we make when investing in risk assets.

- I could have run 10,000 other simulations using further tweaks to the portfolio or withdrawal strategy which would have changed the end results even more. You could intelligently rebalance the portfolio by not selling stocks when they get hammered. You could simply increase the original 4% spending amount (in this case $40k) by the inflation rate every year to make spending less variable. There are a million changes you could make which shows why any reasonable withdrawal strategy will require more nuance, flexibility, and continuous planning to be successful.

- When I began to research this piece I set out to show how a balanced portfolio could get you through retirement even with some bad luck at the outset. While the numbers bear this out what quickly became apparent to me is how difficult it can be to run the numbers on a retirement withdrawal strategy.

- This example shows why financial and investment planning is a process and not an event. Investors need to be thoughtful about how they spend down their portfolio but that process extends beyond a spreadsheet.

Further Reading:

What If You Only Invested at Market Peaks?

Re-Visiting the 4% Rule

1I’m ignoring the impact of taxes and fees for this example because it introduces too many factors into the equation and the fact that neither the 4% rule or index funds existed in the 1928 or 1972 examples and the cost of investing was egregious back then. This portfolio is also relatively undiversified across the globe. My resident tax expert Bill Sweet informs me taxes for a married couple in New York state would be in the 7.25% range using 2017 tax rates on a $40k initial withdrawal from an IRA but this doesn’t take into account social security either. Needless to say, these performance numbers are for illustrative purposes only.

2That would be roughly $70k in 1928, $175k in 1972 and around $750k in 1999.

330 in total for the great-grandparents and grandparents and 17 annual withdrawals for Sam’s parents.

4So I started with a 4% withdrawal rate and increased (decreased) each year by the amount of annual inflation (deflation) using CPI as the inflator (deflator).

This post originally ran on November 13, 2018.