A podcast listener asks:

I was hoping you could try and explain the bond bubble risk. A third of my portfolio is in a Vanguard bond fund. If there is a bubble, what could I stand to lose in % terms?

Here’s a short video Michael and I did on this one:

https://www.instagram.com/p/BwcR2cxD0hy/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

The idea that a bad year in the bond market is a bad day in the stock market isn’t just a nice soundbite. The data checks out.

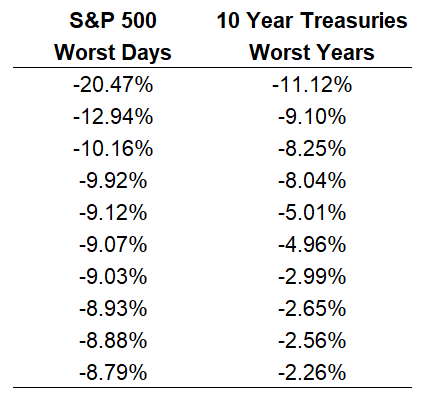

These are the 10 worst daily returns for the S&P 500 and the 10 worst annual returns for 10 year treasuries going back to 1928:

It’s hard to believe but true that intermediate-term government bonds have experienced exactly one double-digit down year over the past 90 years or so.

Stocks, on the other hand, have experienced eleven double-digit down years in this time, including six different years of losses in excess of 20%.

This risk-reward relationship works in both directions. The 10 year has had 18 years of double-digit positive returns since 1928 while the S&P 500 has had 51 double-digit up years.

You can get a better sense of the risk-reward relationship between stocks and bonds by looking at the long history of their annual returns.

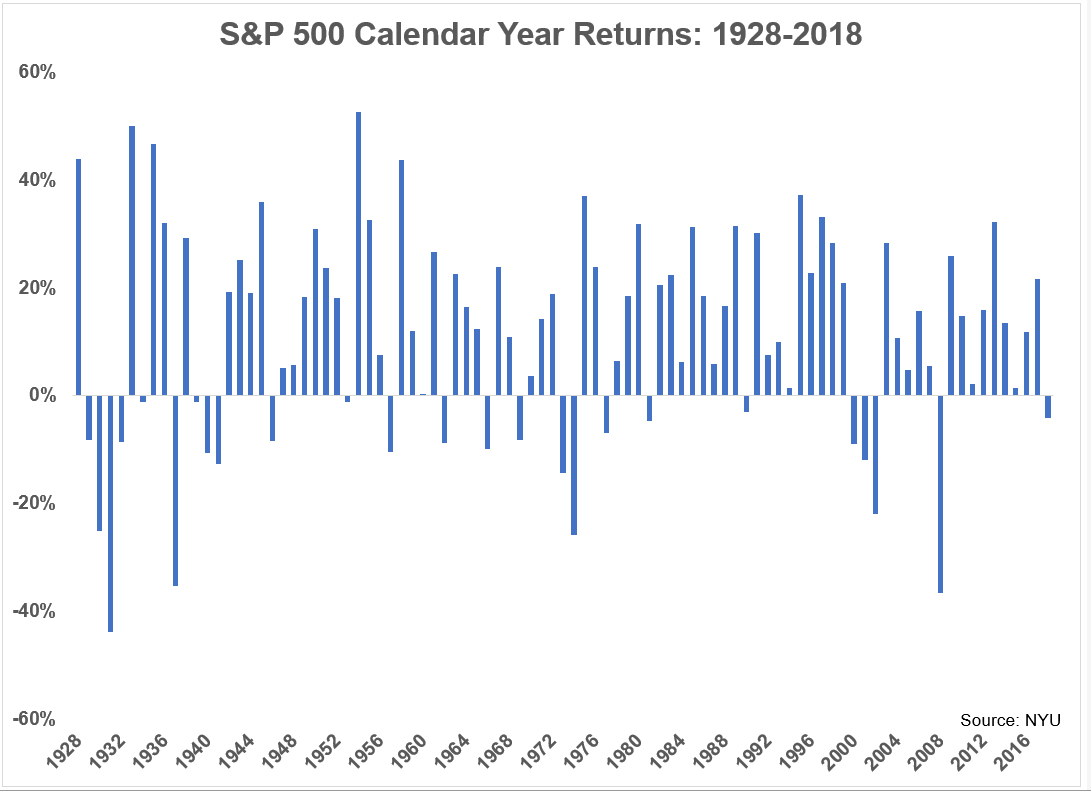

First, here are the annual returns for the S&P 500:

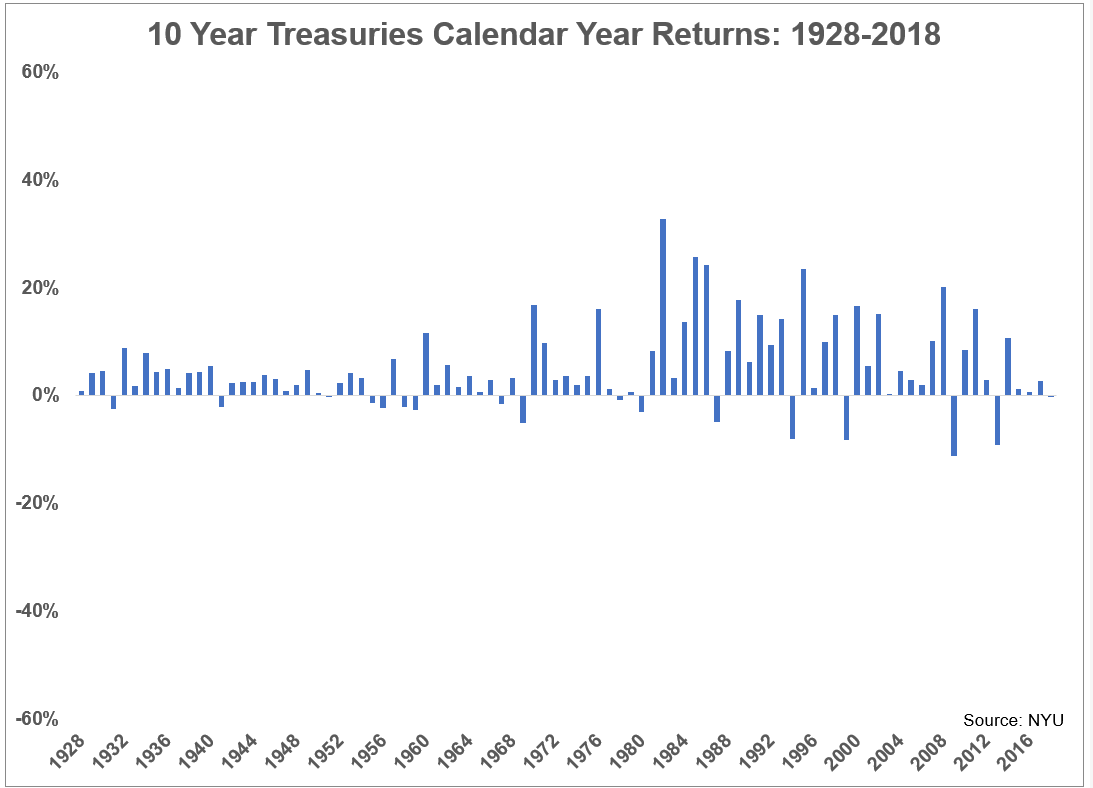

Now here are the calendar year returns for bonds on using the same scale:

The contrast is stark between the two main asset classes.

Stocks are much more volatile, with a wider range of results from year-to-year and a much bigger difference between gains and losses. To compensate for the risks involved, stocks have earned roughly 9.5% annual returns in this time.

Bonds are much less volatile, with a narrower range of results from year-to-year and a much smaller difference between gains and losses. To compensate for the lower risks involved, bonds have earned roughly 4.8% annual returns in this time.

There’s been plenty of bond bubble talk over the years but stocks will always be the biggest risk to a portfolio when thinking in terms of a market crash or large nominal losses in value over the short to intermediate term.

This idea is difficult for some people to wrap their heads around because there is an inverse relationship between interest rates and bond prices.

Anything is possible in the markets so I suppose interest rates could always skyrocket in a relatively short period of time. If that were to happen bonds would certainly get dinged. But on the bright side, investors in bonds would then be earning a higher rate of interest on the new bonds in their portfolio.

But we did see an enormous repricing in interest rates to the upside, most people would have a lot more to worry about than the bonds in their portfolio.

Either way, when building a durable portfolio, it makes sense to think about what’s possible but it’s far more intelligent to plan for what is probable.

The probabilities tell us bonds are far safer than stocks in the short-term. Over the long-term, that relationship is flipped on its head.

So it’s important for investors who would like a more balanced risk-reward relationship to remember that the risk of a crash is almost always going to be greater in stocks than bonds.

Further Reading:

The Case For Bonds