Congress passed the Revenue of Act of 1978 to lower tax brackets on individuals. Within that act, there was a short 900-word section 401(k) which was added with the intent of limiting executive compensation (Narrator: It did not have that effect).

Ted Benna, an insurance company consultant at the time, realized this part of the tax code could be used for both employee and employer retirement contributions. It was initially used by banks as a way to transfer bonuses to employees in a tax efficient manner.

Thus, the defined contribution 401(k) plan was born.

The individual limit was actually more than $45k for the first few years of existence before dropping to $7k in the mid-1980s and slowly working its way up over time. The contribution limit for 2019 is $19k.

Although 55 million Americans participate in 401(k) plans, which hold in excess of $5 trillion, many people see the shift from defined benefit plans (pensions) to defined contribution plans as a huge mistake and a burden on workers.

Retirement savings are a burden on the majority of individuals but the past system wasn’t as generous as people make it out to be.

Surprisingly people were enamored with 401(k) when the plans were initially launched. The following comes from a great retrospective in Barron’s on the 40 year anniversary of the 401(k):

By the late 1980s, many large companies had 401(k)s, and employees loved them. “HR managers were hearing, especially from younger employees, that people appreciated the 401(k) plan much more than the defined-benefit plan,” he says. “Whether or not it was in the employees’ best financial interest, that was how it was perceived because they could see these account balances building up. And what’s the defined-benefit plan to anybody under the age of 50? It’s a formula that they don’t understand.”

It makes sense investors would rather see an actual market value than try to calculate their annual stipend using a formula that may or may not be the same when they actually reach retirement age. The present value of a future stream of pension payments could be massive but most people have a hard time wrapping their heads around this and would prefer a tangible number.

Then there’s the fact that your pension money might not be exactly what you had planned, especially if you work in the private sector:

In one memorable moment, when Benna met with executives of Bethlehem Steel, a human-resources manager politely dismissed his suggestion that they add a 401(k), noting that the company took care of its employees. The steel maker went bankrupt in 2001, and the U.S. Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. took over Bethlehem’s retirement obligations, with many employees getting a cut in expected benefits.

Many are nostalgic for an era where employers took care of their employees in retirement but it’s possible that era was never as rosy as people make it out to be.

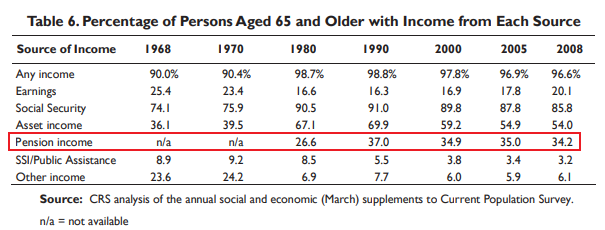

A 2009 Congressional report looked at the various sources of income retirees received from the 1970s through 2008 and found there was never a large majority of retired people who were covered by workplace pensions:

In 1975, 22% of persons aged 65 and older received income from pensions earned through previous employment or as the surviving beneficiaries of workers who were receiving pensions. The percentage of people 65 and older receiving income from pensions rose until the early 1990s, peaking at 38% in 1992. The proportion of the elderly population receiving pension income has fallen slightly since 1992. In 2008, 34.2% of people 65 and older received pension income.

Here’s this trend in table form:

So there was never a time when everyone was receiving a pension. It just may have seemed that way because many of the largest corporations at the time often offered their employees pensions.

Pensions were also a relatively small percentage of retirees’ income during this period. In 1975, income from pensions made up just 14% of the total income for people 65 and older. That number peaked out at 22% in 1993 and made up just over 19% by 2008, which amounted to an average payout of $16,000.

Obviously, I’m sure no one would turn down $16k/year in perpetuity from their employer but it is worth noting there hasn’t been a period in America where every employee’s retirement was covered by their employer.

The 401(k) plan is far from perfect and it hasn’t lived up to its lofty expectations from the outset. In the early days, roughly 50% of employees were offered access to this type of plan with hopes of reaching a 95% penetration rate. Instead, that number is now well less than half.

Small business employees are often not eligible for a 401(k) because it’s too onerous or expensive to run one for a small number of people. And if they do have access many times the costs are outrageous. I would love a universal plan that covered anyone who had a job.1

One of my biggest worries in the coming decades is how municipalities will handle their underfunded pension status. Even those who do have a pension promised to them could see those benefits cut back.2

So it’s possible even the lucky ones who have access to a defined benefit plan are going to be disappointed in what they actually receive. It would be nice if our employers would take care of us in our old age but it’s just not realistic, especially when you consider how rare it is for people to stick with the same employer for their entire career and the fact that people are living longer.

There was never a retirement utopia where everyone had a pension. But now, more than ever, the majority of people are on their own when it comes to saving for retirement.

Further Reading:

How Hard is it to Become a 401k Millionaire?

1Here’s the Ben Carlson dream retirement system: Everyone who is employed is automatically enrolled in the government’s Thrift Savings Plan. The maximum contribution is $50k/year and this one account can be used as a 401(k), IRA, and 529.

2The only other two solutions as I see it are (1) raise taxes or (2) cut back on public services. My guess is it will eventually be a combination of these two and/or a cut in benefits but the relative proportion of these solutions will likely be determined by each municipality’s fiscal standing and political will to deal with these problems. I’m not hopeful for an easy solution where everyone is happy.