Venture capital is one of the most unique forms of investing in the asset management industry.

The business model is predicated on the fact that the majority of the early-stage investments made by these funds will fail. In fact, multiple failures are expected. The hope is one big winner — a la Google, eBay, LinkedIn, Uber, Airbnb, Facebook, etc. — will more than make up for it.

Relationships also play a massive role in who earns the returns since many of the fastest growing early-stage companies can choose which VC firms to work with.

But with the flood of money into the venture space, investors may have other failures to worry about, namely, that of the VC firms they choose to work with.

Last summer I listened to an episode of Kara Swisher’s podcast, Recode Decode, with Warrior’s owner, former Facebook exec, and venture capitalist at Social Capital, Chamath Palihapitiya. He predicted “a huge, rude awakening” for VC firms that don’t evolve as he described his own firm’s process:

“We do seed, venture, growth, equity, debt, private, public,” Palihapitiya said on the latest episode of Recode Decode, hosted by Kara Swisher. “Once we’ve made a decision to be beside you, we will never go away. We will deploy code, we will deploy people, we will help you every day understand your business better.”

“We’ve spent time deploying code, aggregating data, deep inside the bowels of hundreds of companies, thousands of companies before you,” he said. “What that’s left us with are these artifacts. It’s a knowledge base that says, ‘When you try this, it works. When you try this, it doesn’t work.’ Now you can give people, literally, a punchlist of things that can make their business better.”

“Most of the practitioners are dated, in their philosophy, their framework and their capability.”

He criticized investors who take credit for successful entrepreneurs based on a “gut feeling,” rather than data and iteration, and said LPs will tire of having their money locked up in private securities for a decade or more as fewer companies go public. And the big disruptor, he predicted, could be a tech giant like Google, Microsoft or Amazon directly entering the fray.

It was a strong pitch and made for a wonderful story.

Unfortunately, things have gone downhill for Social Capital in the meantime. Dan Primack of Axios reported on Friday that the firm appears to be done as a major venture investor following a rash of defections by the other co-founders and key employees. An investor in the fund was quoted as saying:

We were suddenly invested in something with a different team and strategy from what we signed up for, but at the time it appeared to be an issue between three guys rather than something deeper.

The time horizon in venture investing is a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, locking up your capital for 10-15 years in an illiquid fund structure can act as a form of forced good behavior in terms of investing for the long-term and allowing these things to play out. On the other hand, if you choose to work with the wrong team/fund or pick an inopportune time to invest, you’ve locked your capital up for 10-15 years with no recourse.

What most institutional investors do to manage this risk is to diversify their venture exposure by investing across a number of different funds over a number of different vintage years (the year the fund is launched).

The downside of this type of risk management is you often end up with sub-par results because VC investing is quite cyclical and there aren’t enough winners to go around for everyone to have a piece.

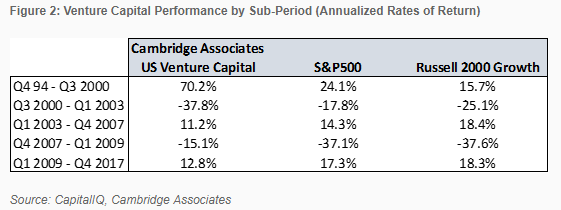

Verdad Capital recently shared a table showing how the majority of the best VC returns came during the dot-com bubble:

Outside of that period, on average, you would have been better off in public equities.

A few years ago, the Kauffman Foundation, a nonprofit with roughly $2 billion in assets shared some lessons from 20 years of investing in VC funds. The report was refreshingly honest in their assessment of the performance they saw in two decades and almost 100 VC fund investments:

- Only twenty of 100 venture funds generated returns that beat a public-market equivalent by more than 3 percent annually, and half of those began investing prior to 1995.

- The majority of funds—sixty-two out of 100—failed to exceed returns available from the public markets, after fees and carry were paid.

- There is not consistent evidence of a J-curve in venture investing since 1997; the typical Kauffman Foundation venture fund reported peak internal rates of return (IRRs) and investment multiples early in a fund’s life (while still in the typical sixty-month investment period), followed by serial fundraising in month twenty-seven.

- Only four of thirty venture capital funds with committed capital of more than $400 million delivered returns better than those available from a publicly traded small cap common stock index.

- Of eighty-eight venture funds in our sample, sixty-six failed to deliver expected venture rates of return in the first twenty-seven months (prior to serial fundraises). The cumulative effect of fees, carry, and the uneven nature of venture investing ultimately left us with sixty-nine funds (78 percent) that did not achieve returns sufficient to reward us for patient, expensive, long-term investing.

When you consider the additional risks taken (higher fees, illiquid structure, riskier companies, etc.) these aren’t the kinds of returns large investors expect.

Yale’s VC portfolio is the flipside of this equation. David Swensen and team have earned ridiculous returns in their venture allocation (although their biggest returns also came during the dot-com era from what I gather).

Investors spend a lot of time thinking about the upside involved in venture capital. And it’s true venture investors play a huge role in shaping the world of technology, not only with their capital but also through advice and guidance to the entrepreneurs they invest in.

But there can be downsides to this space that asset allocators should be aware of. Unfortunately, not every investor in VC land will take part in the next Google.

Further Reading:

Retail Venture Capitalists