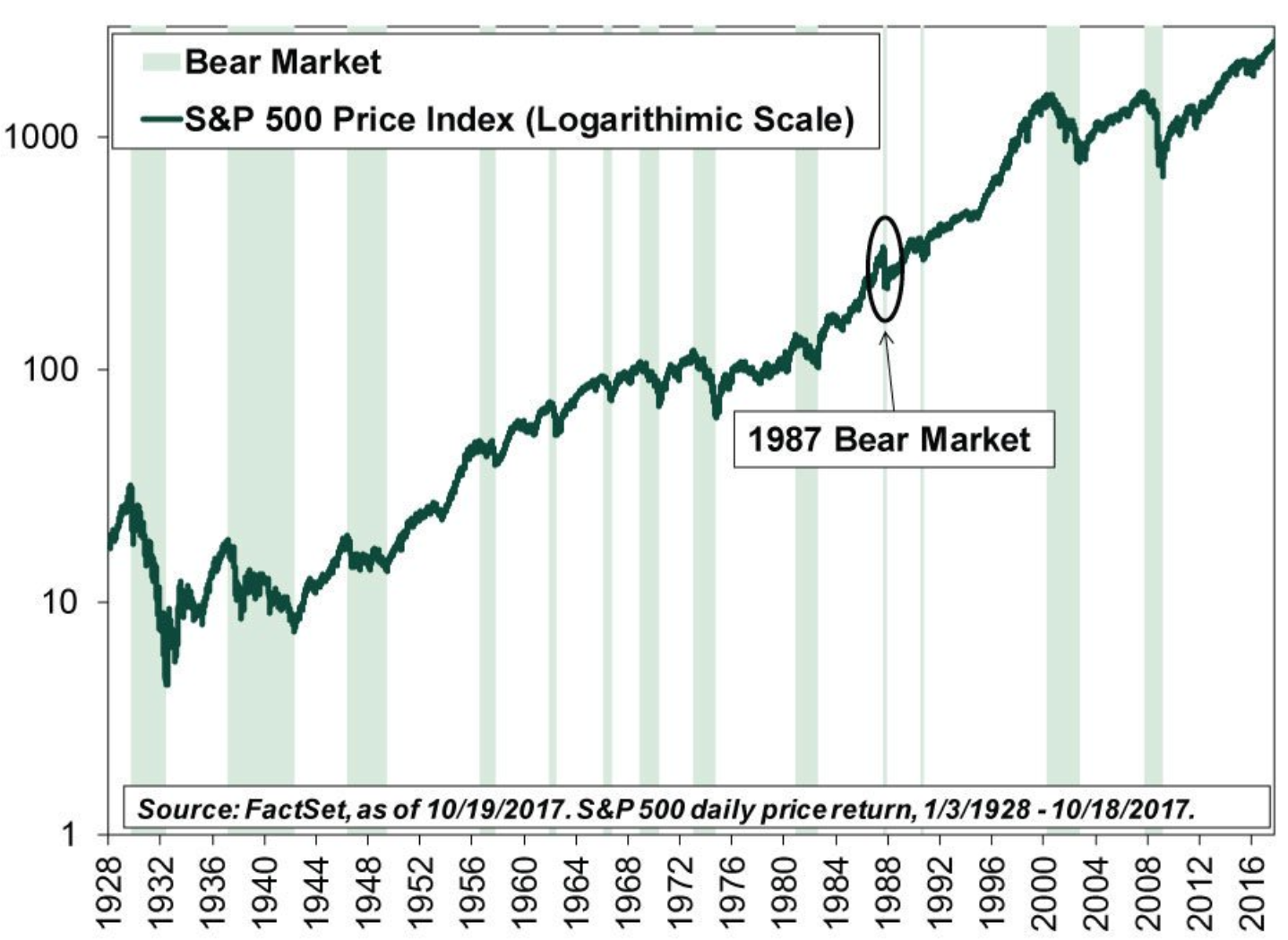

This past week marked the 30th anniversary of the 1987 crash so there were plenty of reflections in the financial media and such. This chart made the rounds on social media:

In some ways this type of chart is beautiful.

It shows the power of human ingenuity, the benefits of long-term optimism, innovation, and progress in the business world.

The point of this specific chart is also to show that the 1987 crash is a mere blip on the long-term chart. You can barely see it in the grand scheme of things.

This was discussed ad nauseam elsewhere but here are a few facts on the 1987 crash:

- Stocks fell 22% on that fateful day in October but they were also down 10% in the three days leading up to Black Monday.

- Stocks were up around 40% in the first ten months and change before they crashed that year.

- Interest rates shot higher just before the crash, as the 10-year treasury yield went from 7% to start the year to nearly 10% by October.

- Even though they fell more than 33% in a few days, stocks still finished the year up more than 5%.

The standard lesson most investors try to show from all of this is that thinking long-term and ignoring the noise means everything will work out just fine.

A few years ago I wrote a post called Would a Repeat of the 1987 Crash Really Be That Bad? where I made a similar argument. This is generally good advice but it’s also extremely naive.

I wrote about this is my first book but it’s worth revisiting. An investor who actually experienced the 1987 crash, with his life savings on the line, commented the following on that post to set me straight:

As one who was actually invested in 1987 (and since 1973), I still have vivid memories of that market crash. It is oh-so-easy to look today at a long-term chart having a tiny blip and say “So what! . . . of course the market recovered . . . those who sold were fools.”

In 1987, market news was nothing like it is today. We had no Internet. We had the next day’s WSJ and Friday’s 30-minute Lou Rukeyser’s Wall Street Week; we subscribed to a few stock newsletters (delivered by snail mail) and Kiplinger and Money magazines . . . that’s about it.

Therefore, though I heard about the crash on the radio as I drove home from work on Black Monday, I was not prepared to find my wife in tears . . . her first words were “You’ve lost our retirement!” (Reading it does not convey the impact of hearing it.)

In real time, the crash was a VERY big event. Fear for a changed future was the natural response. Talking heads were saying “This worldwide event could last for years; our children will have a lower standard of living than we have.”

Long story short— she insisted we sell everything the next day (which was also a significant down day); we eventually re-entered the market.

The key phrase here is ‘in real-time.’ In real-time you don’t get to see that everything works out. You don’t get to look past the fact that many people were predicting another depression due to fallout from the crash.

I can’t even imagine the sheer terror investors must have felt that day and its aftermath.

I’m still not sold on the idea that those who did experience the 1987 crash are better investors for it. Some people who go through this type of market turbulence are always waiting for it to happen again. I’ve seen plenty of this following the 2008 financial crisis. Experience can help in the markets but it can also work against you when you’re constantly fighting the last war.

Investors tend to learn two lessons from studying the past: (1) the right ones (markets are unpredictable) and (2) the wrong ones (investing as if the last crisis or cycle will repeat itself over and over again).

I love reading and learning about financial market history. The best books and pieces are the ones that give firsthand accounts because it gives you a better sense of what people were going through who were actually there. But even then it’s impossible to simulate the feelings, reactions, and emotional strain these types of markets can cause.

Charts can help put things into context but they can also give investors a false sense of security. It’s a mistake to assume that staying the course during periods of severe market stress would have been easy even when it’s the right move.

You can’t simulate the fear and anguish that grips your body and mind during a crash like this when your money is going down the drain.

Further Reading:

10 Things You Can’t Learn From a Backtest