Investors have been hearing about bond market bubbles since the financial crisis. Interest rates have refused to budge but even if/when they do rise most of the people proclaiming this is a “bond bubble” don’t really understand what that means. There’s a huge difference between how bonds and stocks are structured and many of those arguing this case seem to fail to make this distinction. I explain in this piece I wrote for Bloomberg.

*******

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan is worried about a bond bubble. “By any measure, real long-term interest rates are much too low and therefore unsustainable,” Greenspan said in a recent interview. “When they move higher they are likely to move reasonably fast. We are experiencing a bubble, not in stock prices but in bond prices. This is not discounted in the marketplace.”

Greenspan first warned about a bond bubble back in 2010. Although some will say he was early and others would say he was wrong, it makes sense to put things into perspective when discussing bonds in the context of a bubble. As an investment vehicle, bonds are very different from stocks in the way they’re structured — higher up the capital structure, set payment dates, set maturity dates, etc.

Stocks are much more unpredictable than bonds, which is why they tend to see much wider swings in prices, especially in the short-to-intermediate term. Over the long term, bond returns are governed by math more than anything. The beginning interest rate is a good estimate of what long-term performance will be in high-quality bonds (1).

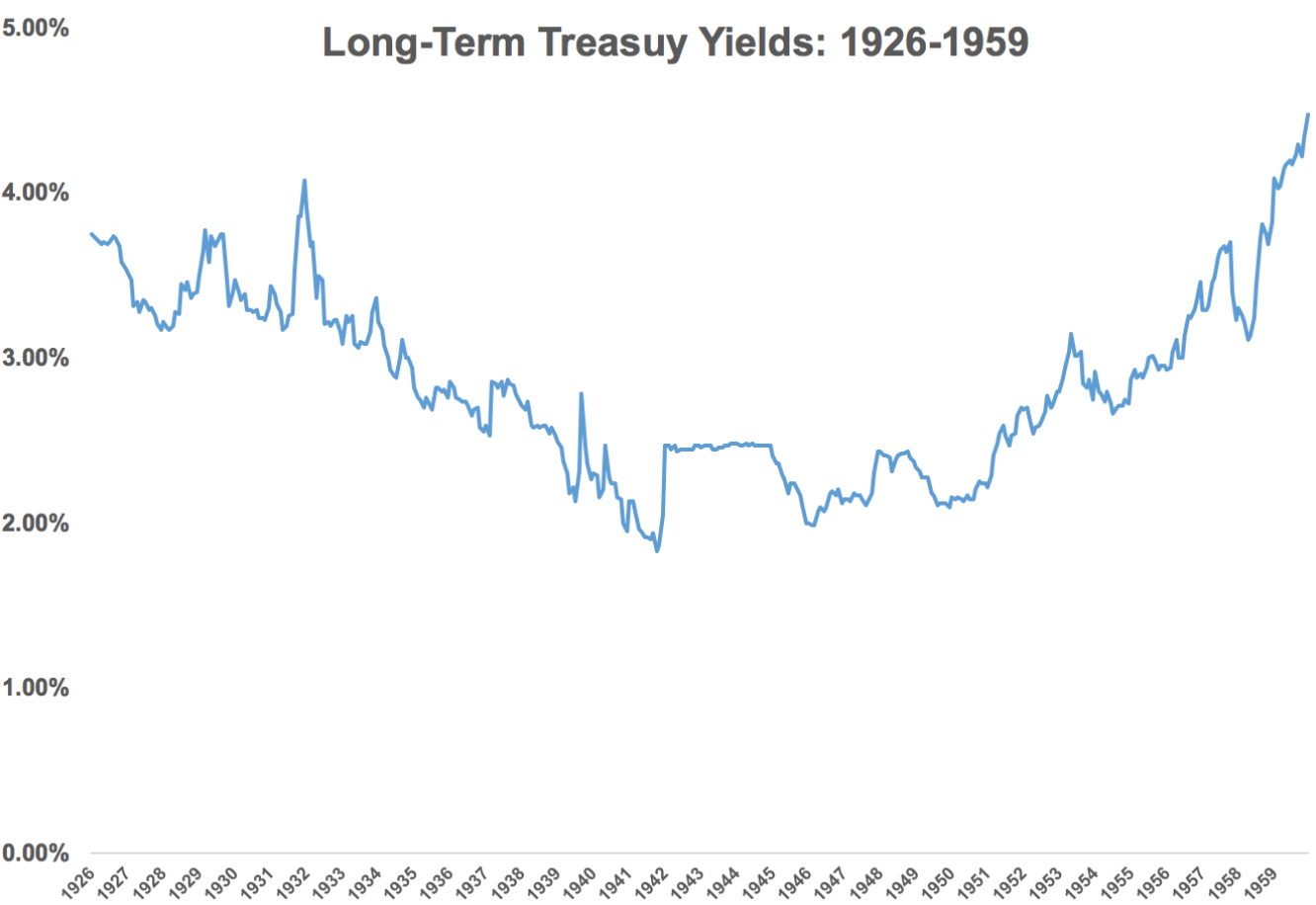

There have only been a few different interest rate regimes, so it’s difficult to use history as a foolproof guide, but we can see how bonds reacted to rising rates in the past to get a sense for the risk profile of these assets. First of all, there’s nothing that says rates can’t or won’t stay low for a very long time. That’s exactly what happened from the mid-1920s to the late 1950s.

Interest rates on long-term government bonds were range-bound between 2 percent and 4 percent for more than three decades in the aftermath of the Great Depression and well after World War II. It wasn’t until the tail end of the 1950s that rates finally broke through 4 percent and stayed there for some time. After that, it was almost an uninterrupted rise in rates for the next 20 or so years.

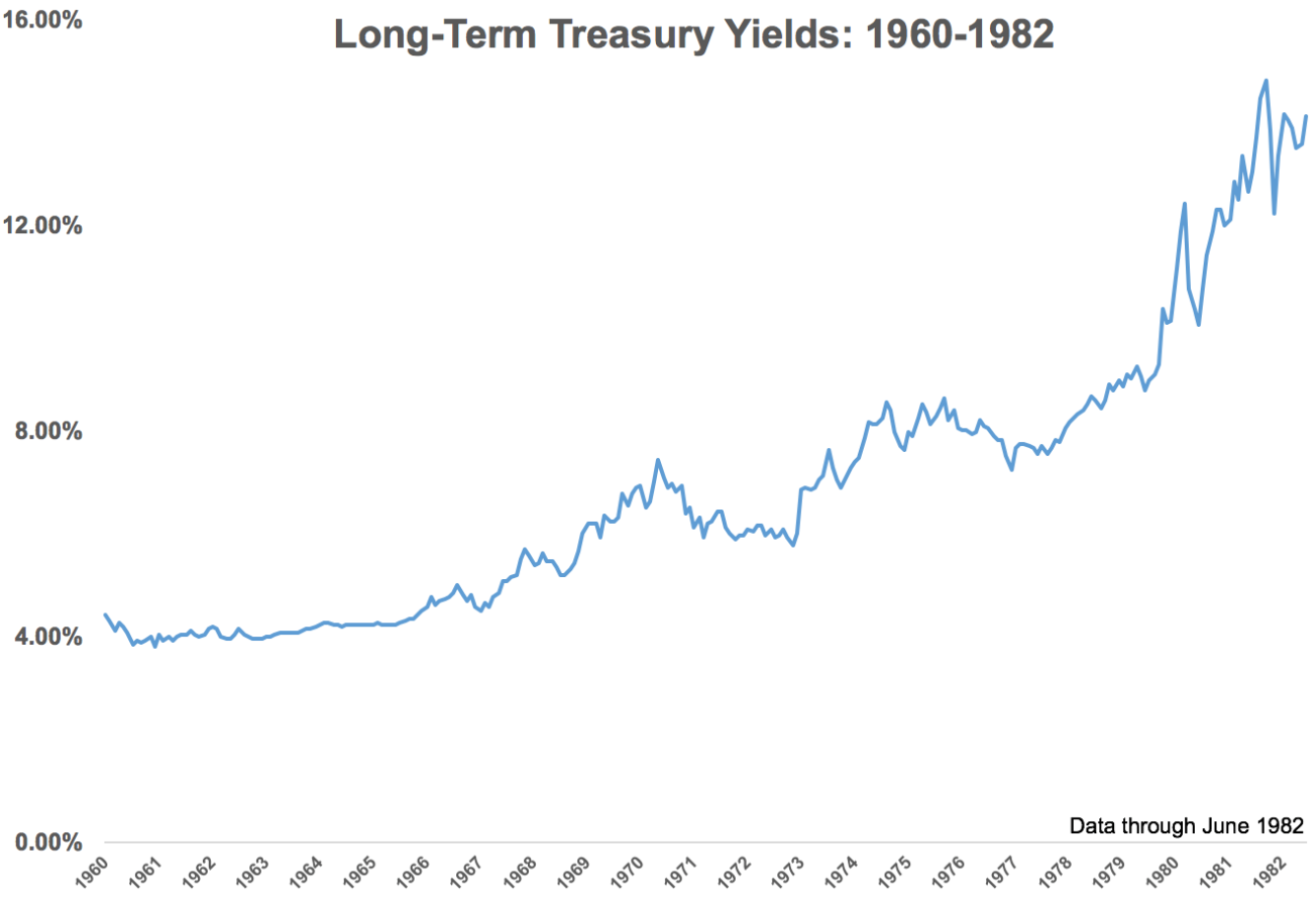

While rates rose somewhat in the 1960s, the 1970s and first few years of the 1980s saw an unprecedented rise in rates from a combination of sky-high inflation and a Fed chairman — Paul Volcker — who was dead set on beating inflation by raising the benchmark rates well into double-digit territory.

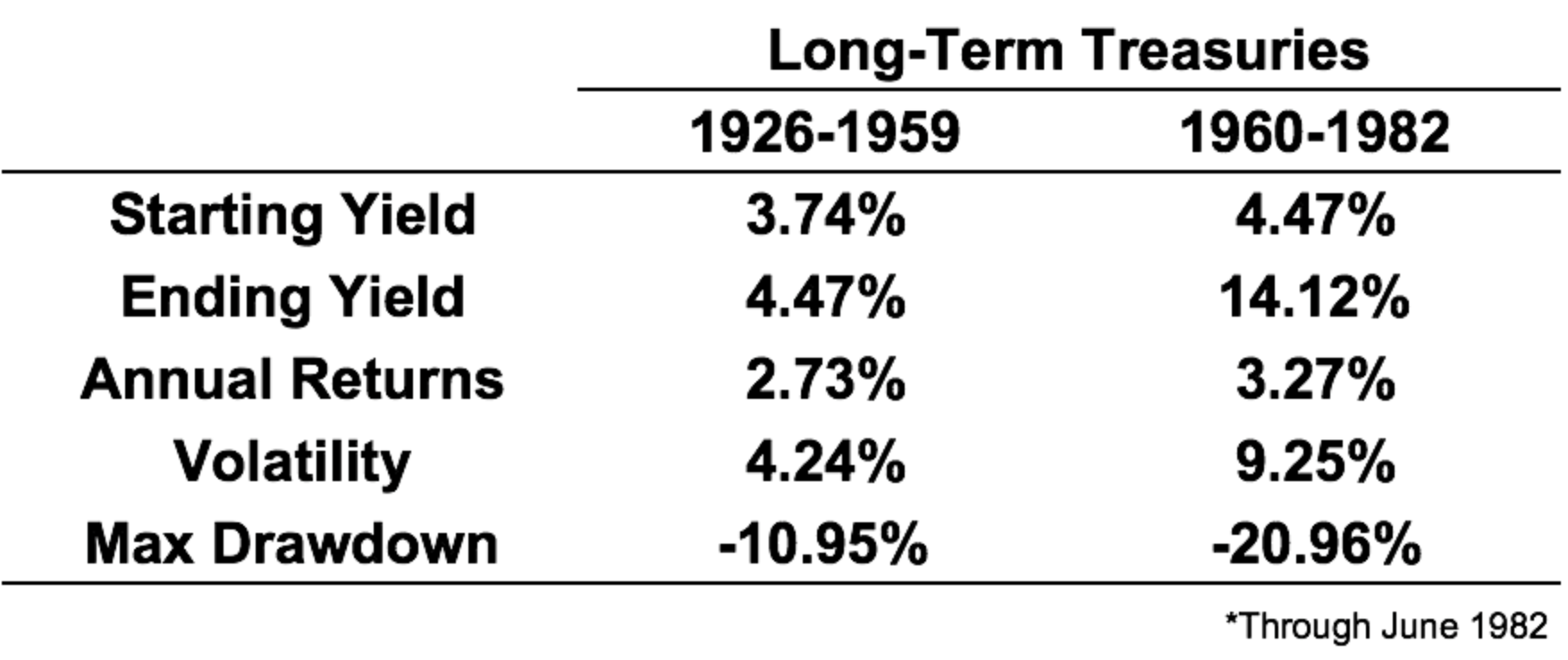

Investors can’t expect this same exact scenario to play out in the future, but seeing long-term rates rising from under 2 percent in the early 1940s to nearly 15 percent in the early 1980s would constitute a good example of how bonds could perform during a rising rate environment. Here are the performance statistics from both periods:

The biggest drawdown for the 1926-to-1959 period came at the tail end in 1959 as rates slowly began to rise. Before that, there wasn’t a single double-digit decline in long-term bonds in this time. And the largest drawdown during the 1960-to-1982 period came when the Fed raised short-term rates to almost 20 percent. Long-term yields started 1980 at around 10 percent and went up to almost 15 percent by September 1981. So even with close to a 5 percentage point rise in yields in under two years, bonds still only fell by as much as a run-of-the-mill bear market in stocks. The worst bear market for long-term government bonds is a loss that is less than the worst one-day loss in the stock market on Black Monday in 1987.

Volatility was much higher during a rising rate environment, but returns were slightly better than the stable rate environment. This makes sense considering that eventually you begin earning a higher yield to offset some of the principal losses from the higher rates. These returns are in nominal terms while the biggest risk to bond investors over the long haul is inflation.

On a real, or inflation-adjusted, basis, long-term government bonds actually lost close to 38 percent in total from 1960 to 1982, taking the annual real returns down to a loss of greater than 2 percent per year (2).

While anything is possible in markets, it’s unlikely we’ll see a crash in high-quality sovereign bonds in the same way that we would in stocks. Bond losses are more like a death by a thousand cuts. Rising yields could impact the multiple investors are willing to pay for stocks as well.

So Greenspan’s bond bubble comments show that investors shouldn’t be worried so much about a bubble in bonds as an unexpected rise in inflation.

(1) You also have to adjust for factors such as credit quality, inflation and default risk for other types of fixed income.

(2) Real returns in the 1926-1959 period were 63 percent in total or roughly 1.5 percent annually.

Originally published on Bloomberg View in 2017. Reprinted with permission. The opinions expressed are those of the author.