Vienna, Austria is one of my favorite cities on the planet. I spent an entire summer living and studying there in college. It was one of the best experiences of my life.

Our classrooms were located in the City Center right across the street from the Vienna State Opera House. It’s a stunning piece of architecture. I attended a liberal arts school so we were required to take a music course so I took an opera appreciation class while I was there. It was my favorite class I took in college.

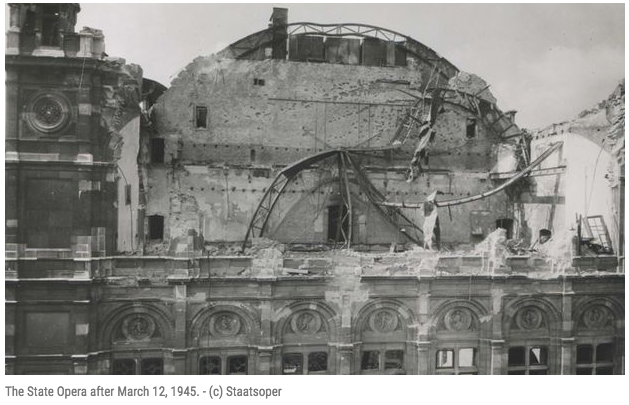

Not only did we attend a number of operas for this class but we also were given a tour of this structure. The building dates back to the mid-19th century. Towards the end of World War II, the opera house was bombed accidentally by the allied forces. Something like 2,000 bombs were dropped on the city, killing tens of thousands of people and destroying tens of thousands of buildings and homes.

The opera house was not spared from the damage. The stage was completely destroyed and the rest of the building decimated by an ensuing fire.

In the rebuilding efforts, there was a lengthy debate by city officials about whether the opera house should be restored or completely demolished and rebuilt. They eventually decided to rebuild exactly as it was before, an effort which took more than 10 years.

There were examples like this all over Europe following the destruction caused by World War II. Most major cities were severely damaged with many reduced to rubble and badly in need of a rebuild. It took some time and a little help from the Marshall Plan, but these cities did rebuild, which is amazing when you think about it.

How did some of these cities and communities survive? After so much pain and damage was inflicted, why didn’t more of these cities simply die out? Why do cities last hundreds or even thousands of years while corporations can flame out during a single recession or change of strategy?

Geoffrey West explores this idea in his compelling book Scale: The Universal Laws of Growth, Innovation, Sustainability, and the Pace of Life in Organisms, Cities, Economies, and Companies. West laid out some wild stats on how difficult it is to sustain a corporation over the long-term:

- 28,853 companies traded on U.S. stock market from 1950-2009. Almost 80% of those companies (22,469) were gone by 2009 (through buyouts, mergers, failure, etc.)

- Fewer than 5% of companies remain over rolling 30 year periods.

- The risk of a company dying does not depend on its age or size as the probability of a 5-year-old company that dies before turning 6 is the same as that of a 50-year-old company reaching age 51.

- The estimated half-life of U.S. publicly traded companies was 10.5, meaning half of all companies that go public in any given year will be gone in 10.5 years.

- There was just a 12 percent survival rate for the firms on the Fortune 500 list in 1955.

Here’s West explaining why it is that companies die but cities don’t:

The fact that companies scale sublinearly, rather than superlinearly like cities, suggests that they epitomize the triumph of economies of scale over innovation and idea creation. Companies typically operate as highly constrained top-down organizations that strive to increase efficiency of production and minimize operational costs so as to maximize profits. In contrast, cities embody the triumph of innovation over the hegemony of economies of scale. Cities aren’t, of course, driven by a profit motive and have the luxury of being able to balance their books by raising taxes. They operate in a much more distributed fashion, with power spread across multiple organizational structures from mayors and councils to businesses and citizen action groups. No single group has absolute control. As such, they exude an almost laissez-faire, freewheeling ambiance relative to companies, taking advantage of the innovative benefits of social interactions whether good, bad, or ugly. Despite their apparent bumbling inefficiencies, cities are places of action and agents of change relative to companies, which by and large usually project an image of stasis unless they are young.

In his research West found the relative amount of capital allocated to research and development decreases as the size of a company increases. The idea here is that the investment in innovation doesn’t keep up with other operating expenses as companies get bigger. Scale also points to the idea that diversity is a hallmark of big cities:

In cities we saw that one very important hallmark is that they become ever more diverse as they grow. Their spectrum of business and economic activity is incessantly expanding as new sectors develop and new opportunities present themselves. In this sense cities are prototypically multidimensional, and this is strongly correlated with their superlinear scaling, open-ended growth, and expanding social networks—and a crucial component of their resilience, sustainability, and seeming immortality.

Most companies become short-sighted the larger they get as it becomes easier to stick with what’s working because it guarantees short-term profits. They resist cannibalizing earlier successes. Cities don’t have the same short-termism baked into their incentive structures. West also figures when a city doubles in size, the people become something like 20% more productive.

The fact that companies die and cities live on can both be a testament to the human spirit. Stocks represent human ingenuity, technological advances, and innovation in the business world. Cities represent community, opportunity, a place to call home, and their own form of innovation.

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- Skills vs. behavior (Collaborative Fund)

- If you bought at the market peak in 2007 you would have doubled your money (Irrelevant Investor)

- The challenge of finding quality investments (Clear Eyes Investing)

- Living in a financial commercial (A Teachable Moment)

- We are all quants now (Abnormal Returns)

- Few market winners, so much dead weight (Bloomberg)

- The need for advice never goes away (Reformed Broker)