The size of the global asset management industry is staggering.

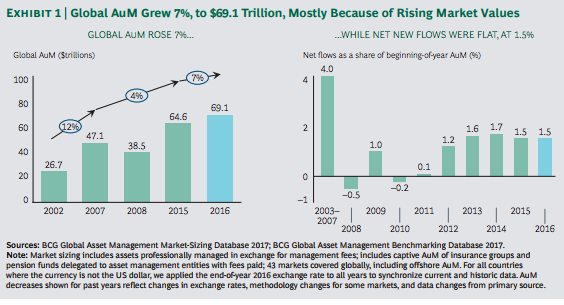

Boston Consulting Group estimates that as of year end 2016 there was close to $70 trillion in assets under management globally (meaning money that paid a fee for the management of assets). Here’s the breakdown showing the growth in worldwide AUM since 2002:

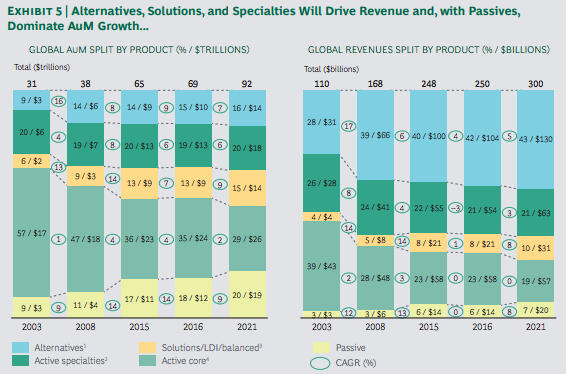

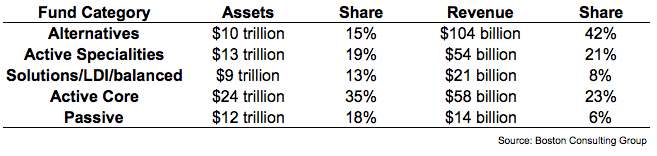

It would only make sense that a staggering amount of assets would lead to a staggering amount of revenue for the firms charging management fees. BCG estimates that the total revenue brought in on these assets last year was roughly $250 billion. They also broke out these assets by the types of products they’re invested in:

A few things jumped out at me from these numbers:

Passive investments have seen a nice growth spurt in recent years but active strategies still dominate the global asset management landscape. BCG estimates that by 2021 passive funds will make up $19 trillion of a potential $92 trillion in assets, just over 20% of the total. It’s nearly impossible to venture a guess where global markets will be in 5 years but even now passive funds make up just shy of 18% of the total global assets under management.

The biggest opponents of passive investing often come from active investment firms and you can see why from these revenue numbers. While passive funds account for 18% of assets, they earn just 6% of the fee revenue. It’s no wonder active firms are constantly bashing indexing and ETFs. They know a shift to lower cost products will put fee pressure on their margins.

Active fund managers like to try to convince people they are now the underdogs against firms like Vanguard and Blackrock. This is strange considering the active fund industry earns 94% of all revenue globally.

I was told early on in my career that if you want to understand people’s motives and incentives, just follow the money. In the fund industry, the money is in alternative assets. While alts make up around 15% of the total asset pie with $10 trillion under management, they earn 42% of fee revenue.

Just to make things a little clearer from the graphs above, here is the breakdown by both asset and revenues:

My guess is this fund makeup will look more and more like a barbell over the coming years. Investors will continue to funnel money into passive funds but institutions will take more of a low-cost approach on the one hand with ETFs and a high-cost approach with alternatives on the other. Maybe the margins will come in a little bit but since the large-scale investors are used to paying such outrageous fees in the alts space it will be difficult to dial things back too much. They’re anchored to high fees and they’ll likely continue to pay high fees.

I came across a great stat on venture capital investing last week from Wealthfront’s Andy Rachleff (himself a very successful VC):

Most large asset pool managers would like a 5 – 10% allocation to venture capital because of its past returns and anti-correlation with other asset classes. Unfortunately, they can seldom reach their desired allocation because there aren’t enough VC firms that generate returns that justify the risk. That’s because the top 20 firms (out of approximately 1,000 total VC firms) generate approximately 95% of the industry’s returns. These 20 firms don’t change much over time and are so oversubscribed that they are very hard for new limited partners to access.

Venture capital is a unique asset class in some ways but this is basically how I view the institutional investment world. Everyone assumes they are or should be one of the top 20 funds or at the very least, that they can model themselves after the top 20.

Institutional investors all want to believe they’re “sophisticated” so they gladly pay high fees and assume they can all access the top decile of hedge funds, venture capital and private equity.

Are there certain investors who have done well and will continue to do well investing in alts? Certainly, but it’s not a large cohort in my estimation.

Those people who work for the alternative investment firms are getting much richer than their actual investors. Hope is an expensive strategy but it’s been a pretty lucrative one for the alternative investment world.

This will continue for as long as institutional and family office investors are willing to pay exorbitant fees in exchange for a good sales pitch.

Sources:

The Innovator’s Advantage (Boston Consulting Group)

Demystifying Venture Capital Economics (Wealthfront)

Further Reading:

Why Investors in Alternatives Perform so Poorly