I just finished reading David McCullough’s critically acclaimed book, The Wright Brothers. Going into it I didn’t really know too much about the fascinating story beyond that historic first flight at Kitty Hawk in 1903.

That first flight garnered little fanfare at the time (most people just didn’t believe it was possible), but the innovation that followed was remarkable. Charles Lindbergh flew across the Atlantic by 1927. Bombers were used successfully in WWII. And Neil Armstrong took man’s first steps on the moon in 1969.

Despite this unbelievable progress, in the grand scheme of things, human flight is still relatively young. Commercial flights didn’t become popular until the 1950s or 1960s for much of the public.

I think people can take for granted just how amazing it is that we can sit in a metal tube and fly through the air like a bird all while using wifi and watching movies (Louis CK has the best take on this here).

This got me thinking about a few other things that are relatively new as it pertains to the markets and the economy. Here are three that come to mind:

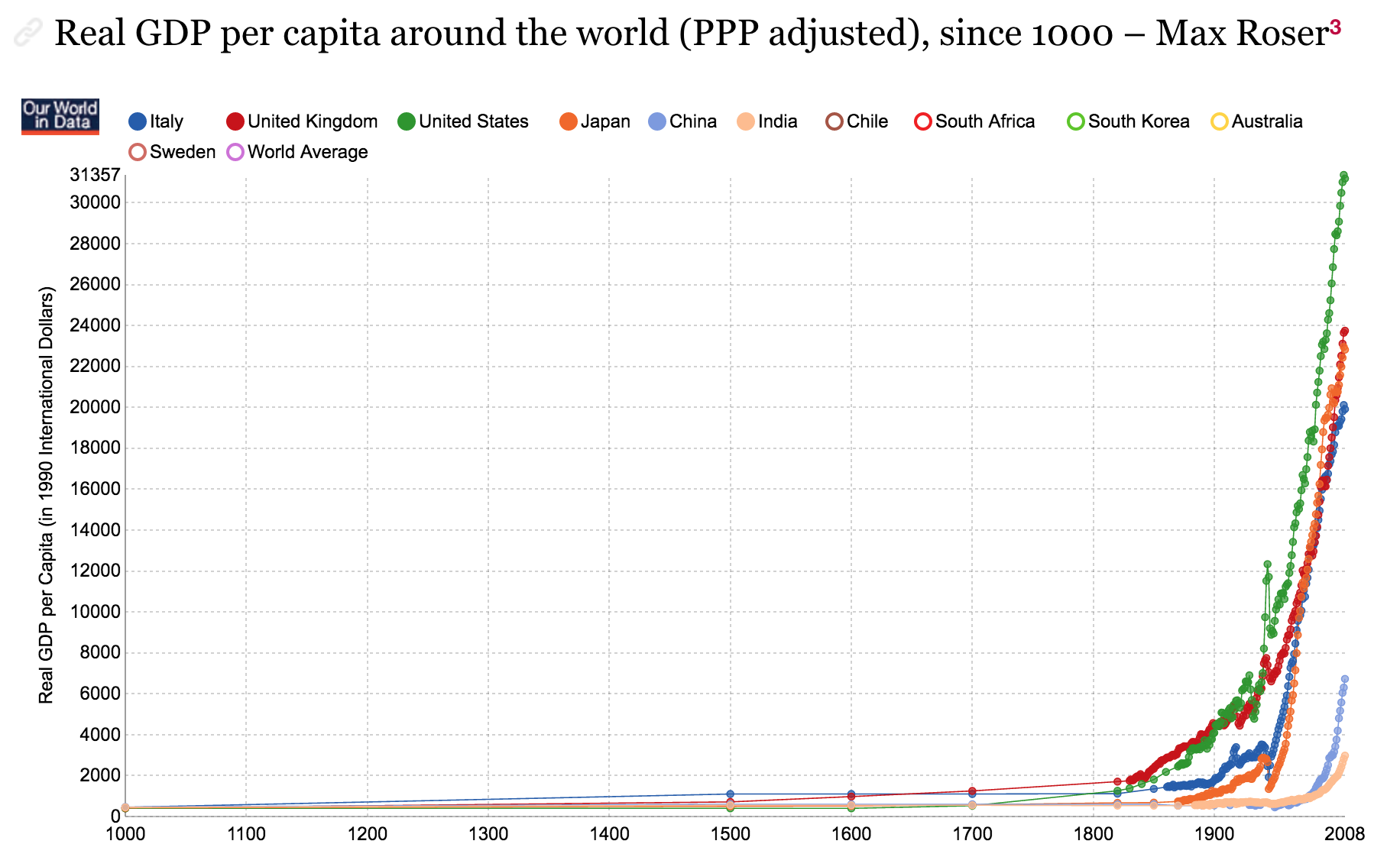

1. Economic growth. For tens of thousands of years there was little progress or economic growth in the world. People didn’t really even believe in progress or getting better for the future. Things looked fairly similar from century to century. It wasn’t until the Scientific Revolution in the 1500s and 1600s eventually paved the way for the Industrial Revolution that people actually started to believe that progress was even possible. Before then the global pie basically stayed the same size.

Here’s a good chart on this from Max Rosner:

Today we act like economic growth is our birthright, but this idea of progress and innovation is really only a couple hundred years old. It hasn’t been around for very long.

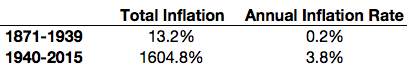

2. Inflation. According to Peter Bernstein, the cost-of-living index was less than 30% higher by 1940 than it had been 140 years earlier. And starting with the panic of 1873, over the next twenty plus years the prices of goods and services in the U.S. fell by almost 40%. Here’s a good breakdown that shows how things have changed:

This doesn’t mean there wasn’t any inflation. There was, but there were almost 70 instances of annual deflation in the pre-1940’s era. Sustained inflation is a relatively new phenomenon.

3. Historical Stock Market Data. We investors today are spoiled with the amount of historical data and tools available for research and analytical purposes. I remember my first boss in this business showed me all of the old models and asset allocation tools he had to build by hand on Lotus 1-2-3 (a pre-Microsoft Excel spreadsheet program) in the early-1990s. It took him years to build these things out to make them functional because there weren’t many other options. Today these tools are available for free at any number of websites.

And historical stock market data was only really collected for the first time in the 1960s. In the late-1950s, Louis Engel, a VP with Merrill Lynch, was trying to figure out how well stocks had done over the long-term when compared to other asset classes. No one really had that data available so he contacted the Chicago Graduate School of Business, who said they would perform a historical study if Merrill Lynch would agree to fund it. So in the early 1960s a group of professors collaborated on a historical dataset of NYSE listed stocks from 1926-1960 (small caps weren’t added until later). It took them nearly four years to complete what is now known as the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP). CRSP data provided, basically for the first time ever, the average long-term returns in the stock market.

Stocks for the long run seems like common knowledge to nearly all investors today, but this knowledge has only been around for a handful of decades.

There are so many other facets of modern life that we take for granted — indoor plumbing, air conditioning, fridges, radios, televisions, the Internet, wifi, cellphones, suitcases with the little wheels and the list could go on.

I guess my point here is that it’s easy to assume that the way things are today is the way that they’ve always been. This is why I’m always amazed when people are 100% certain about anything these days in terms of how the future will play out. This stuff is still all so new that it would be impossible to make concrete conclusions with any degree of certainty.

It’s also a good idea every once and a while to take a step back and appreciate how far we’ve come.

Further Reading:

Trading Costs & The New Market Averages

No One Knows What Will Happen

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- Consistency in fund returns is a mirage (Basis Pointing)

- Living in multiply time frames (Irrelevant Investor)

- Has the U.S. debt reached a tipping point (Fat Pitch)

- How to lose by beating the wrong benchmark (Dan Egan)

- 10 problems caused by low interest rates (Monevator)

- The shift from active to passive isn’t what it seems (Bloomberg)

- My wife’s mother needed a kidney and I was a match (WSJ)

- Diversification is now more important than ever (Cordant)

- Kings lose crowns but teachers stay intelligent (TRB)

- Why smart people make bad decisions (Collaborative Fund)