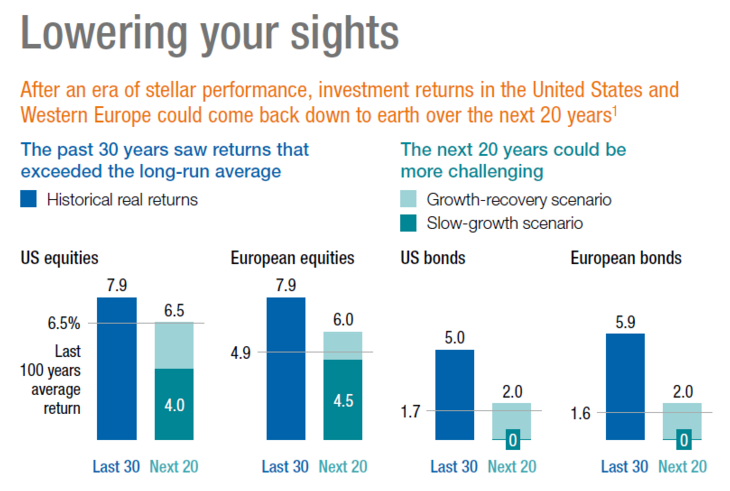

Plenty of people in the finance world were talking about the study put out last week by the giant consulting firm McKinsey on the prospects for lower market returns over the next 30 years than we’ve experienced over the past 30. Here are the numbers from the report:

And here’s the takeaway from Bloomberg:

Turning 30 just got a lot scarier.

A coming collapse in investment returns means that people that age today will have to work seven years longer or save almost twice as much to end up with the same nest egg as those of roughly a generation ago.

So says the research arm of McKinsey & Co. in a new report that argues that investors of all ages need to resign themselves to diminished gains.

The consulting company maintains that the last 30 years have been a “golden era” of exceptional inflation-adjusted returns thanks to a confluence of factors that won’t be repeated. They include falling inflation and interest rates, swelling corporate profits and an expanding price-earnings ratio in the stock market.

The next two decades won’t be nearly as lucrative, even on the optimistic assumption that the world economy snaps out of its recent funk and resumes growing at a faster clip, according to the McKinsey Global Institute report titled “Diminishing Returns: Why Investors May Need to Lower Their Expectations.”

First of all, plotting out economic or market assumptions over 30 years is kind of silly because it’s basically impossible. (My colleague Barry Ritholtz covers some of the the problems with this type of forecasting here.) The stock market is nearly impossible to predict, as is economic growth or inflation, but bonds are more or less governed by the laws of math over the long-term. So at first glance, sure, these numbers could be reasonable. Regardless, let’s assume for the sake of argument that their forecast is correct.

Do lower returns over the next 30 years automatically spell doom for Millennials who are investing their money?

Not necessarily.

The biggest problem with this line of thinking is that is fails to consider the sequence of these returns. Even if stocks do rise 6.5% per year for the next three decades, the path they take to get there will matter much more than the annual average return.

Let’s look at two examples to see why this is the case.

Scenario #1: A young person starts saving $5,500/year and increases that amount by 4% each year to account for inflation and salary increases. They save for 30 years and earn a steady 6.5% each and every year. After 30 years they would end up with roughly $743,000.

Scenario #2: A young person starts saving the same $5,500/year and increases that amount by 4% each year to account for inflation and raises. They save for 30 years as well, but instead of earning a steady 6.5%/year they earn just 3.2%/year, with alternating annual returns of +12% and -5%, for the first 20 years. Then they earn 13.5%/year in the final 10 years. This still works out to an annual average return of 6.5% just like in the first scenario, but because these returns were so poor in the early stages of saving and higher in the latter stages, this person’s ending balance was closer to $1,000,000.

Both scenarios saw the exact same amount saved over the exact same time frame and earned the exact same annual returns. But the sequence of those returns caused a huge difference in their ending balances. The second scenario was more than 30% higher than the first one.

The thing that most young investors can’t seem to wrap their heads around is the fact that you want lower returns during your early years when you are a net saver. It allows you to buy more shares in the stock market at a lower price. A decade or even two decades of poor returns would be an amazing opportunity for Millennials. Throw in a couple of market crashes in there and that’s even better.

This example illustrates the fact that luck can have a lot to do with how much money you end up with. Some people are simply born into a perfect market cycle while others have more of an uphill battle. Whatever future market returns we end up seeing, one thing is for sure — they will not exist in a steady state like you see in a simple retirement calculator. Averages never tell the entire story.

This report did have one piece of great advice for young people — it makes sense to increase their savings rates and plan for the worst. Not only does this mindset allow compound interest to do most of the heavy lifting for you, but a higher savings rates, and thus slower lifestyle creep, is a great way to give yourself a margin of safety in case things don’t go as planned in life (and they never do).

The biggest problem is that is can be difficult for young people with little financial or market experience to have the guts to continue buying when things don’t look so good and markets are falling or going nowhere. That’s probably why one of the best financial decisions you can make early in your working life is to automate your investing contributions, increase the amount you save every year and then don’t look at your statements very often.

No one has control over the market’s performance over their lifetime, but you can control your personal savings rate and how you handle your biggest asset — human capital.

Source:

End of Golden Era for Investors Spells Trouble For Millennials (Bloomberg)

Further Reading:

Trading Costs & The New Market Averages

Financial Advice For My Fellow Millennials