There was a story in Bloomberg today about the University of California’s endowment fund and their latest moves to shake up the portfolio:

The University of California’s endowment, which manages $2 billion in hedge fund investments, plans to pull money from the worst-performing managers and redirect assets to top firms, the state system’s investing chief said.

The number of hedge fund managers will be cut to about 10 from 32 as soon as June, the latest move in a revamp of the university’s $95.7 billion in pension and endowment assets that began two years ago under Chief Investment Officer Jagdeep Bachher.

The one number that should stand out to you here is the fact that they currently have 32 hedge fund managers in their portfolio. (I agree with the move to consolidate but time will tell if they are simply chasing past performance here or not.) When you include private equity, venture capital, real assets, hedge funds and public managers many of these institutional funds can hold anywhere from 50 to in excess of 100 different money managers. This is a problem on a number of fronts.

First of all, the due diligence and monitoring costs for a portfolio with this many managers can be enormous. Not very many funds, even at the institutional level, have the resources, expertise or operational capabilities to oversee that many managers. Second of all, throwing a bunch of different funds and strategies into a portfolio is not exactly diversification — it’s a form of phony diversification.

Diversification only works if you’re able to understand how the different portfolio components fit together and complement one another. It would be nearly impossible to understand your portfolio exposures and manage risk when utilizing so many different money managers. It’s difficult to estimate these costs of complexity, but they make for an inefficient investment program in the wrong hands.

The main reason many investors have performed so poorly using alternative investments is because they don’t understand that there’s a huge difference between traditional and alternative investments in terms of portfolio management. It’s not necessarily that the funds themselves have performed poorly (although many have); it’s how they’re being used in an overall portfolio.

With traditional investments:

- Diversification is one of the few free lunches in the markets that allows you to increase your long-term risk-adjusted returns by adding additional assets together.

- Diversification by geography, asset class, market cap and strategy can improve results.

- Average returns will almost certainly lead to above average results in terms of your peers because index returns beat the majority of active funds.

With alternative investments:

- Diversification in alternatives almost ensures that you will see sub-par results.

- Diversification by vintage year, buyout size/type and hedge fund strategy can actually hurt your results when it’s done in the style box fashion of traditional portfolio management.

- Average returns will most likely lead to below-average market results (especially in hedge funds).

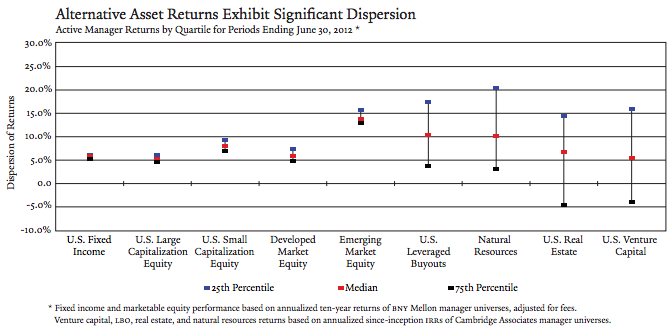

Take a look at this chart from the Yale Endowment annual report a few years ago for the dispersion in results (traditional investments on the left and alternatives on the right):

There isn’t a huge performance difference between the top and bottom performing asset managers in stocks and bonds, but within alternatives there is a huge difference between the top and bottom performers. The more managers you add the this space, the easier it becomes to pick a poor-performing fund. Over-diversification can increase your risks of sub-par performance because you increase your odds of picking a fund manager that blows up. With traditional investments you pretty much know what you’re getting yourself into. This is not so with alternatives, especially if you don’t have the expertise to understand these more complex investment strategies.

I understand why so many institutional funds manage their portfolios this way. The high dispersion in alt manager performance leads to a huge concentration risk if you pick the wrong fund. And alts have a much higher blow-up potential because they utilize leverage and illiquid securities. Therefore, most investors aren’t comfortable investing in just a select few fund managers or strategies. So there’s a double-edged sword of the desire for diversification on the one hand and the problem with too much diversification on the other.

I’m not saying it can’t be done, but in many ways this is a form of ‘threading the needle’ in investment management. As David Swensen said in that very same Yale report:

Selecting top managers in private markets leads to much greater reward than identifying top managers in public markets. On the other hand, poor private manager selection can lead to extremely disappointing results as a consequence of high fees, poor performance, and illiquid positions.

The margin for error is much higher in alts. If you were going to go this route, my sense is it would work best by pairing traditional investments with a select few alternative managers. It’s not an easy solution by any means, but outperforming is not easy in this space. The problem is everyone assumes they can consistently pick top quartile funds in the Lake Wobegon of institutional asset management.

Sources:

California Endowment to Yank Money From Worst Performing Funds (Bloomberg)

Yale Endowment Report 2012

Further Reading:

Are Private Equity Returns Overstated?

Now here’s the stuff I’ve been reading lately:

- When do you want to take your risk, now or later? (Reformed Broker)

- Are we due for a recession? (Irrelevant Investor)

- Stock buybacks demystified (EconomPic)

- Poking holes: Find your strategy (228 Main)

- Index funds and Goodhart’s Law (Investor Field Guide)

- Managing Private Wealth (Shawn Leamon)

- The most horrendous lie on Wall Street (Fortune)

- The 20 best investing blogs of 2016 (College Investor)

- When winners fail (Basis Pointing)

- Is it time to abandon emerging markets? (Cordant)

- Preparing for a crash even if it doesn’t come (The Street)

There seems to be something wrong in the number of assets – “university’s $95.7 billion in pension and endowment assets”. Is it really $95.7 B?

Harvard University’s endowment was $36,429,256,000 at the end of fiscal year 2014. It had the largest endowment among 1,140 ranked institutions.

Ravi, the University of California system is made up of 10 different universities, which is likely why the number is high compared to Harvard.

Yup and I will say that everything I’ve read says that run a pretty tight ship so maybe this will work out for them. Just seems like a bit of a performance chase

From what I just read, I can’t believe they run a tight ship. It is a performance chance. Talk about a rookie error. I would not let this guy running the $79 billion touch $10 of my money.

When, following the dot-com crash, my firm began offering hedge funds as an alternative to classic stocks and bonds, our PA’s began to tell clients that they could expect stock like returns with bond like risk. Of course, actual returns were more bond-like as many firms flooded the market and drove down returns.

The UC decision speaks to a larger problem of over generous pension schemes whose funding via investment returns has fallen short for years. California, like many states, is unwilling/unable to raise state contribution levels and union members are loath to contribute more and suffer a decline in income. As a result, funds chase returns in whatever investment vehicle de jour they hope will offer higher levels of return.

I also agree with your comments on the numbers of managers that the UC was using, which only makes sense if the managers somehow compliment each other. In theory (and then only up to a certain point of diversification), it can make sense, but my greater suspicion is that it is yet another tactic employed by manager search firms to justify their existence and fees.

Yeah the funding shortfall is going to catch up with many of these pensions eventually considering the expected returns they’re using. I think it really comes down to understanding your limitations as an organization which many of these funds are unwilling to do.

This sounds like a disaster waiting to happen. Either this manager is overwhelmed, has lost his way and is now out of control, or he never knew what he was doing to begin with.

Moving form worst to past best is definitely chasing performance. That is stupid, plain and simple. With alt’s, my opinion is that you are hurting returns by worrying about potential losses in the rest of the portfolio. You can’t be invested in everything. Complexity usually = poor returns. I do not invest in something, then try to hedge my investment. If I thought about hedging it, I would not have made it in the first place.