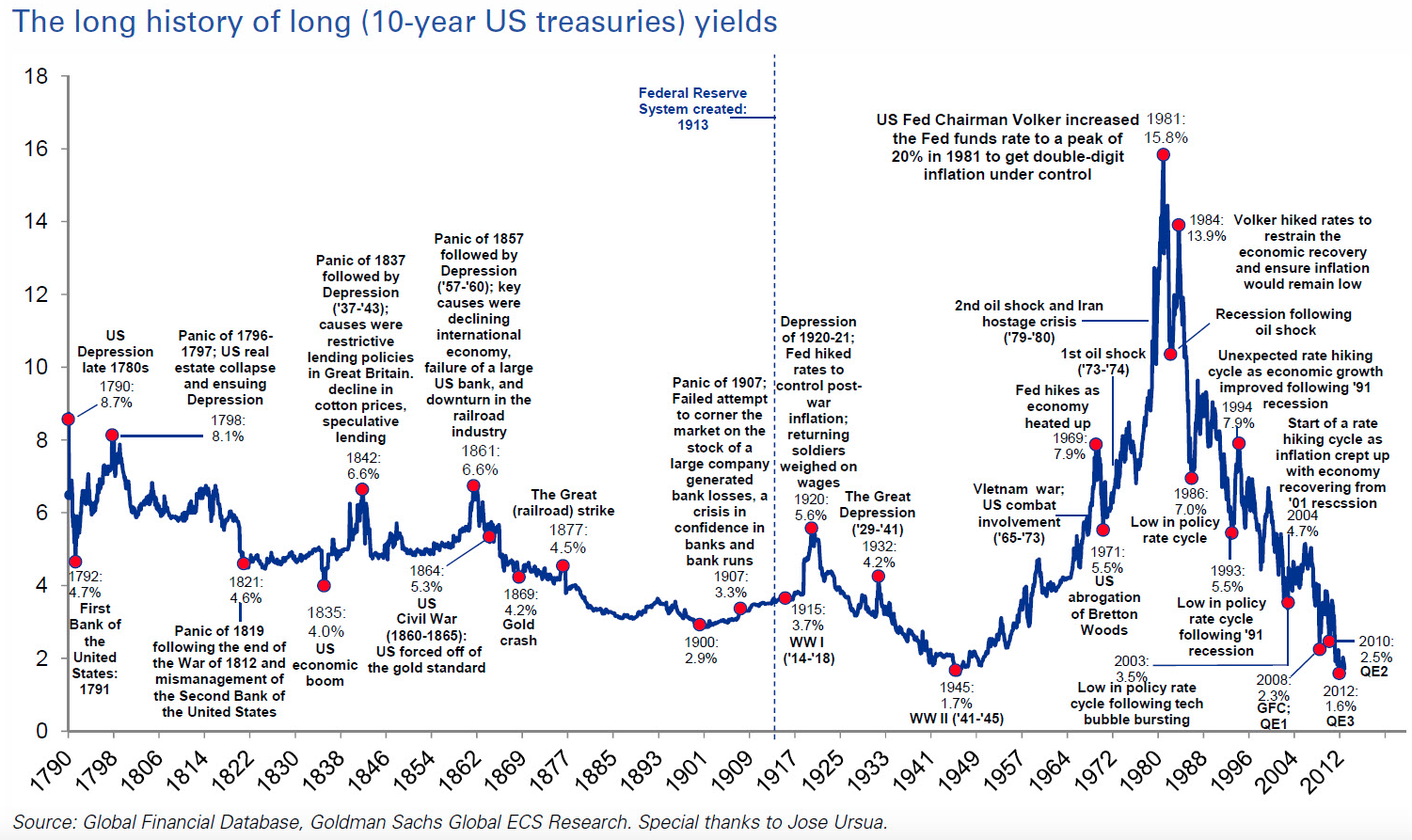

As I’ve stated in the past, one of the hardest things to do in all of finance is predict the direction and magnitude of interest rate movements. The variables involved are seemingly endless. The chart above shows interest rates over the past 225 years. Many use this historical construct to build their forward-looking interest rate forecasts. Someone will be proven right from this exercise, but it very well could be for the wrong reasons.

Let’s look at a handful of interest rate forecasts seen through the lens of different behavioral biases:

Recency Bias: “The trend in rates has been down for 30+ years. Why fight it?” This has certainly been the right call, especially when so many have been predicting higher rates the past few years. But this line of thinking will become dangerous some day as many will be caught flat-footed at the turn. Interest rates cycles seem to last longer than most, but all market trends must come to an end at some point.

Anchoring: “Interest rates went to 15% in the early 1980s. Surely we’re heading there again in the not-too-distant future.” Many investors that experienced the inflationary-1970s period know firsthand how difficult it was to invest in a rising rate environment. It’s difficult for people to avoid anchoring their forecasts to that enormous peak on the graph.

Representativeness: “Rates will stay lower for longer like the aftermath of the Great Depression. No, they’re sure to scream higher like the 1950s-1980s time frame.” Per Kahneman and Tversky, representativeness entails looking at an event and making a judgment as to how closely it corresponds to other events found in your sample. When you look at that graph there are really only a few different long-term cycles — falling rates, rising rates and sideways rates — and all occurred over multi-decade periods. The sample size we have to draw from as far as interest rate environments go is fairly small. Chances are the future will be completely different than the past.

The Availability Heuristic: “Interest rates will never rise. The Fed will never raise rates.” This is a mental shortcut where people rely exclusively on immediate examples that come to mind. The Fed hasn’t raised rates in over a decade and interest rates have been low for some time now, so many extrapolate this trend indefinitely into the future.

Gambler’s Fallacy: “2010: Rates are going to rise. 2011: Rates are going to rise. 2012: Rates are going to rise. 2013: Rates are going to rise. 2014: Rates are going to rise. 2015: OK, this time rates have to rise.” Like the coin flipping guesser who thinks seeing six tails in a row makes it more likely that they’ll see a heads on this next flip, some pundits seem to operate under the assumption that they have to be right eventually (and they probably will if they keep at it, but not because of any great foresight).

Hindsight Bias: “I knew rates were never going to rise.” Many people assume that the lower rate for longer scenario was obvious now that they’ve seen things play out. Basically no one was predicting rates would be at these levels following the financial crisis. Investors will continue to look back at the direction and magnitude of future rate moves and assume it was obvious. Things only look obvious in the markets in hindsight.

I’m not suggesting every single interest rate forecast (or forecaster) is completely biased in their views, but it always makes sense to reassess your opinions in light of potential cognitive dissonance.

Further Reading:

What if Risk Free Returns Slowly Go Away?

Now for the stuff I’ve been reading lately:

- Do people want to be fooled? (Irrelevant Investor)

- Eight things I learned from Judd Apatow (Waiter’s Pad)

- The power of common sense (Motley Fool)

- What good are long-term returns if your investors don’t earn them? (EconomPic)

- How the amateur investor can beat the professionals (Washington Post)

- Six rules for disciplined investing (ETF.com)

- Why financial blogging will never be the same (Abnormal Returns) and Josh Brown on the state of financial blogs (Reformed Broker)

- Investing lessons from the Marine Corp (WSJ)

- The reason pension funds stick with hedge funds (Bloomberg View)

Subscribe to receive email updates and my quarterly newsletter by clicking here.

[…] Voters Believe It? (FiveThirtyEight) • What Interest Rates Can Teach Us About Behavioral Biases (A Wealth of Common Sense) • SEC Nominee Works at Think Tank Dedicated to Blocking SEC Regulation (The Intercept) • […]

[…] love this long term chart via Ben Carlson looking at the various behavioral issues that arise around every major Treasury peak over the past […]

So are you saying that I am exhibiting biases whether I decide to:

1) Buy bonds today and hold to maturity

or

2) I wait for interest rates to go up before I buy bonds to hold to maturity

Behavioral biases are great to discuss using post-mortem data. But the real question is, “how can I invest my money”. And those “biases” only serve to make the investor doubt themselves, rather than make them good investors. Perhaps you can enlighten me as to how knowing about those biases has made you a better investor?

I think every investor needs to admit their limitations. The entire investment process comes down to regret minimization in my mind. Knowing where your blind spots are and having the ability to admit your weaknesses is one of the best ways to stay humble in the markets. It doesn’t mean you have to change your investing posture, just that you should be cognizant of it.

I agree on the humility aspect 100%. Unfortunately, that realization of how little we actually know happens only after many years of actual investing.

This is why I also believe that an investor who has a plan on how to invest their money should stick to that plan. Ideally there is a reason on why they selected the plan, and it helps the investor in achieving their goals. That plan should help the investor with the process of investing.

My issue with behavior finance is that it talks a lot about behavior of a pool of investors – but I am not sure it offers much in terms of actual remedies. The actual remedy should be to read a lot and learn a lot. When I read some statements I wonder if their sample includes mostly those who just look at stock investing as gambling.

For example I won’t become a good doctor by working on my biases. I would become a decent doctor by spending a lot of time in school, and a lot of time practicing medicine. Hope all that makes sense.

From GFD’s notes on this series: “The Federal government completely paid off its debt in the 1830s, so New York State Canal 5% bonds are used from 1835 to June 1843.”

Until WW I, US Treasury bond issues were few and far between. Typically, the maturity of the outstanding US bond issue gradually declined from 25 to 40 years to near zero, when another long-term issue replaced it.

Consequently, this series only roughly indicates what a nominal 10-year T-note yield might have been during the 19th century. Since chronically upward-sloping yield curves only developed after the establishment of the Federal Reserve in 1913, interpolation errors in the 19th century using longer maturity bonds likely cancel out in direction.

So like most data before the 1900s, proceed with caution?

Very timely post as I’m currently reading Behavioral Finance for the L3 exam in June. I think the key here is making sure you understand the possibility of

your views being biased and coming up with counterarguments to

ensure you’re comfortable with the investment decision.

Time to go review my notes again to make sure I have a firm grasp on the material!

Well said, It’s not that you have to change your mind, just that you should allow for the possibility of being wrong.

[…] in Financial Markets (Bloomberg) What Interest Rates Can Teach Us About Behavioral Biases (A Wealth of Common Sense) Morgan Stanley: No Limit to What Amazon’s Web Services Can Disrupt (Barron’s) SEC Nominee […]

[…] What Interest Rates Can Teach Us About Behavioral Biases by A Wealth of Common Sense […]

[…] Click here to read the full article on the graph above and click on the graph below to goto the full article. Interest rates are an interesting phenomenon. As I drew out for you in the Coca Cola earnings yield post, sometimes it is pertinent to know where bond yields are relative to the earnings yield. It comes down to opportunity cost. Immense disparities between stock market earnings yields and bond yields occur very rarely, but when you find yourself in such a divergence, it might be a good idea to re-calculate your opportunity cost. […]

[…] It is always interesting to see how human biases have a huge impact on the decisions we make. Most of the time we do not realise that we are doing it – What Interest Rates Can Teach Us About Behavioural Biases […]

[…] Wealth of Common Sense (via Barry […]

[…] What Interest Rates Can Teach Us About Behavioral Biases – A Wealth of Common Sense […]

[…] What Interest Rates Can Teach Us About Behavioral Biases […]