There are some compelling cases being made right now in both academic and investor circles that future U.S. stock market returns will be muted from current levels. Some are going a step further and claiming that real returns over the next decade or so will be zero or even negative.

One of the most heavily cited examples given for these forecasts is Robert Shiller’s Cyclically-Adjusted Price to Earnings (CAPE) ratio. Professor Shiller has a treasure trove of historical information on the CAPE and other well-known market metrics going back to the late-1800s on his website. The fact that the data covers such a long time frame offers investors a large sample size to test their return-forecasting models. But I still think it’s a stretch to think we can accurately forecast market returns using this series.

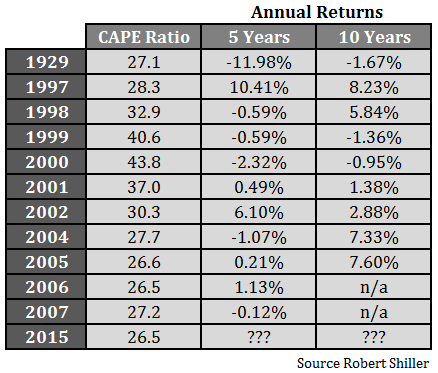

The CAPE at the start of 2015 came in at 26.5 times the trailing ten year’s worth of inflation-adjusted earnings data. Looking back at the long history of the CAPE ratio, this level hasn’t been breached too often and it’s far above the average of 16.6x going back to the start of this data set. I looked back on Shiller’s data and found every calendar year that began with a CAPE of 26.5x or higher along with the subsequent annual five and ten year return numbers on the S&P 500:

As with most historical market data, you can always pick and choose certain scenarios to bolster or disprove a current forecast. Shiller’s data goes all the way back to 1871. So out of nearly 150 years, there have only been twelve times in which the market started out the year with a CAPE ratio of 26.5x or higher. There are two ways you could look at this data:

- Wow, the majority of the market’s biggest historical crashes and low returning periods over the past 100 years have coincided with an elevated CAPE ratio.

- Wow, in over nearly 150 year’s worth of data there is an extremely limited sample size in which to draw conclusions from the information on elevated CAPE ratios.

Anyone with a healthy dose of common sense would probably choose to look at the data in both of these ways. It’s true that above average CAPE ratios have led to lower than average stock market returns in the past. Ten years out the annual return average is just 3.3%, while the average five year gain was just 0.2% annually. But it’s also true that this limited sample size has seen a wide range of returns between the best and worst case scenarios.

It’s also amazing how clustered the above average CAPE periods have been over the past twenty years or so. Since the beginning of 1997, the first time since 1929 that a year started out with a CAPE above 27, the S&P 500 is up 386% or almost 9% per year. (This date also happens to closely coincide with Alan Greenspan’s famous Irrational Exuberance speech in December of 1996.) Over that time the average CAPE ratio is 27.1. Granted there were periods in-between that saw terrible losses in that time and the CAPE ratio fluctuated, but that’s how things work in the stock market.

My point in this exercise is to show how little pundits and forecasters have to go on, even if they’re using one of the longest market data sets at our disposal. Sure, you could use this data to set reasonable expectations and maybe even offer a range of possible returns. Even then, there’s a good chance the future could see outliers either higher or lower than the historical precedent. I would take any future return predictions from these levels with a huge grain of salt, especially if the party making the forecast isn’t willing to consider a wide range of potential outcomes.

Anyone claiming to have anything approaching certainty in their return forecast for the stock market is nuts.

Further Reading:

The CAPE Ratio and a Range of Historical Outcomes

Torturing Historical Market Data

When looking at an individual investment it is useful to see historical earnings adjusted for inflation. Using the CAPE you get to see the relative valuation of the investment compared to historical valuations. This is logical.

What is illogical is to attempt to use this formula on an index, such as the S&P 500. Every year there are companies that go bankrupt or companies that nearly go bankrupt and get acquired on the cheap. These companies have bad earnings before their eventual demise and removal from the index. These companies are replaced by new companies to keep the index at 500 companies. The flaw in the CAPE is that it continues to use the failed companies earnings (or more appropriate, losses) when calculating the historical 10 year inflation adjusted earnings. Why would I care about the price of the current 500 companies relative to the earnings of a different set of companies over the past 10 years? The earnings over the past 10 years are artificially deflated relative to the actual historical 10 year earnings of the current 500 companies.

The quick response to this question would be ‘well if its constantly happening, then it smooths out over time’. That is incorrect, as extreme market conditions such as 2008 lead to more bankruptcies and index churn. 2008 artificially distorts the denominator of this equation which produces a higher CAPE today.

Great points and I agree. It sounds great in theory, but really it’s not an apples to apples comparison. Larry Swedroe has a great piece out today on some of the other flaws if you’re interested:

http://www.advisorperspectives.com/newsletters15/25-are-grantham-and-hussman-correct-about-valuations.php

Strong points all around, James. However, I think they are overstated. If we take, as an example of an extreme year, companies in 2008 removed from the S&P 500 index, only 8 had losses (note I’m not saying that all those other ones that were removed were strong companies but rather the thought that only those with losses are removed is incorrect). Most of them were removed because their market cap became too small, despite positive earnings.

I also don’t fully accept that “2008 artificially distorts…” With all due respect, 2008 did happen. It wasn’t artificial. You are correct that it produced greater “churn” in the index but even still, it wasn’t substantial turnover. I don’t mean to argue too much as I’m not a huge fan of internet comment fights but one final point. If we were to say that 2008 distorted the trailing p/e on the downside why couldn’t we just as easily say that 2006, for example, distorted it on the upside?

Take a look at this piece that demonstrates how many stocks have been removed across global markets:

http://www.starcapital.de/docs/2015-06_MSCI_Country_CAPE_Keimling.pdf

It’s tough to say either way how much of an effect this is having. I actually wrote about this recently too:

https://awealthofcommonsense.com/how-innovation-is-affecting-market-valuations/

[…] Historical market data is what you make of it. (awealthofcommonsense) […]

[…] Historical market data is what you make of it. (awealthofcommonsense) […]

During these times of “high” valuation, an investor can review forward returns and mitigated volatility produced from a simple switching strategy in order to gain historical perspective over the myriad of CAPE articles that published . https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1mdon_cto48rvs2_lKWyMWrfqSIh8K0phfe7tThle8qQ/edit?usp=sharing

Even Shiller himself concluded the CAPE accurately forecasted only 40% of future 10-year stock returns. So even if you presume Shiller’s methodology has power, you accept the odds are worse than a coin flip it will accurately predict future 10-year returns at any given time.

But the methodology behind CAPE is fundamentally flawed. Attempting to remove the influence of the economic cycle on profitability is very odd. The last 10 years included one of the worst recessions in modern history, which skews the last 10 years of earnings lower. But the earnings during the great recession will NOT at all influence firms’ profitability looking forward. The conditions are different. Firms’ forward-looking profitability depends on the conditions and variables arising over the period ahead. Past earnings and price movement tell you nothing about the future earnings and price movements. CAPE, is backward looking and tells you very little about the future.

Further, CAPE can’t tell you when the market will arrive at the CAPE predicted returns. Stocks could appreciate strongly over the next seven years, then experience a prolonged bear market, or vice versa. Periods with lackluster 10-year returns, like the last decade, can have perfectly fine runs in the interim—like stocks did from 2003 through 2007. Most investors would likely want their assets to participate in the good years, capturing those opportunities, and try to avoid at least some of the bad years. CAPE proffers no clues for how to do this.

To the investor, CAPE is a curiosity, not a useful investing tool.

That number sounds about right to me. You’re right that the timing of a bull or bear market towards the end date of a return forecast has a lot to do with the outcome. If anything it’s an expectations tool, not a good predictor of future returns.

CAPE and other valuation metrics do a good job of projecting future returns. Though its not always perfect. If you look at the long-term charts, you’ll notice that there are periods where returns undershoot and overshoot. Markets have overshot expected returns for like 20 years. Odds are future returns could be worse than projections because they’ve spent so much time overshooting. Secondly, if you look at your data, odds are very high that 5-year returns will be nothing. 1997 benefitted from a lifetime bubble and 2002 was at a market bottom. Other than that, all 5-year returns were bad. Given where the market is now, 5-year returns are very likely to be nothing or negative.

It’s possible but it’s also a possibility that we continue to overshoot again. That’s why even over 5 or 10 years it’s still so hard to predict return numbers.

[…] Read Also: CAPE Fear Of Lower Returns by Ben Carlson via Wealth Of Common Sense […]

[…] Read Also: CAPE Fear Of Lower Returns by Ben Carlson via Wealth Of Common Sense […]

[…] Read Also: CAPE Fear Of Lower Returns by Ben Carlson via Wealth Of Common Sense […]

[…] I’ve been discussing over the past year or so (see here, here, here, here and here), there have been a number of high profile predictions made for lower than average returns […]

[…] 1900-1975, the average CAPE ratio on the S&P 500 was 14.7. Since 1975, the average CAPE has been 20.1. Are falling costs and […]