“We display risk-aversion when we are offered a choice in one setting and then turn into risk-seekers when we are offered the same choice in a different setting. We tend to ignore the common components of a problem and concentrate on each part in isolation.” – Peter Bernstein

Let’s say you were given fifty-fifty odds of either winning $8 or $32. Not a bad deal, but let’s also assume you were given a fifty-fifty chance of losing either $8 or $32.

You would think that either way you would feel pretty good about either option in the first set of odds and pretty bad about losing money in the second set of odds. Yet when this study was actually performed that’s not what happened at all.

The subjects actually felt slightly positive when they lost $8 because they avoided losing $32. But when they won $8 they reported a feeling of dissatisfaction because they didn’t win $32. They felt good about losing $8 because the gamble was framed in terms of losses and they felt bad about winning $8 because the gamble was framed in terms of gains.

This is what behavioral economists call framing. Framing refers to the fact that we tend to draw different conclusions from information depending on how it’s presented to us.

Another example comes from a research study that shows how doctors can actually change their patient’s mind about a surgical procedure based on how they frame their diagnosis recommendation. Patient decisions were much different when the doctor said “you have a 90% chance of survival” versus “you have a 10% chance of mortality.”

More patients opted in for the surgery when it was framed in terms of survival while more opted out when presented with the mortality option. It’s the same exact odds but just presented using a different point of view.

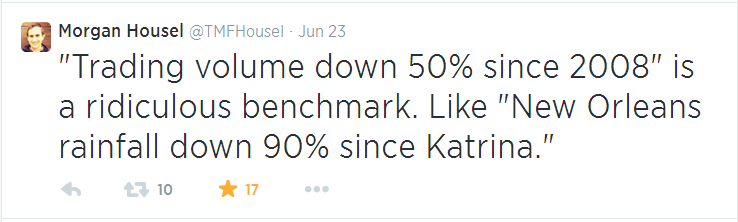

Framing occurs frequently in the financial markets because it’s the ultimate playground for gains and losses. We constantly see comparisons of market and economic data today versus those in the peak years or those in the trough years. Morgan Housel had a perfect take on this type of framing:

There will always be a point in time you can use to frame data to make it look positive or negative. You just have to ask yourself how reasonable your comparison is and how biased your conclusion will be based on how the data is presented.

Unemployment numbers can be framed based on gains since the height of the financial crisis or in terms of losses since the 1990s. Earnings numbers can be framed based on prior peaks or troughs. Economic growth and living standards can be framed against prior generations.

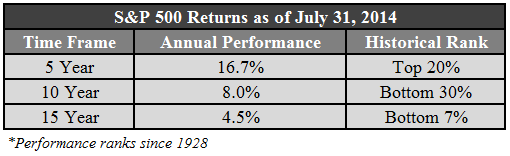

Here’s an example using different starting points for annual returns on the S&P 500 along with their ranks based on historical performance data:

Based on this data and how you want to interpret the numbers you could make the following arguments:

- The 10 and 15 year numbers are well below long-term averages so the market can’t be too extended from here.

- The 5 year numbers are well above average and are unsustainable so the market must either crash or see lower returns going forward.

The S&P 500 is currently right around the 2,000 point level. Here are two market scenarios to consider — (1) The market shoots up by 20% over the next year to get to 2,400 before falling by 30% or (2) The market goes nowhere for the next year and then falls 16%.

Which situation is worse for investors?

Actually both scenarios end up with the same exact result because the S&P 500 finishes at 1,680. But the first option would be much more painful for investors because it would be framed in terms of gains that weren’t locked in before a huge drop as opposed to a much smaller correction in the second scenario.

And by the way, that 1,680 level on the S&P would take us back to levels seen in October of 2013. Did you feel pretty good about the stock market in October of 2013 when it was up 25% on the year at that point? I’m sure most did.

Perception can make a huge difference in how we feel about our finances at different points in time.

Investors can take advantage of data to reflect their confirmation bias while other times we’re simply tricked by how something is presented to us. Analyzing hard data is an important part of the investment process, but how it’s presented to us and how we frame it can have a huge impact on the perceived conclusions.

Understanding that we all have cognitive biases such as framing is half the battle for reducing errors.

[…] Framing and Investment Decisions […]

[…] Ben Carlson, “Perception can make a huge difference in how we feel about our finances at different points in time.” (A Wealth of Common Sense) […]

[…] Ben Carlson at A Wealth of Common Sense looks at how framing affects our investment decisions and outcomes. […]

[…] Further Reading: Forecasting Your Emotions How Framing Affects Investment Decisions and Outcomes […]

[…] Reading: How Framings Affects Investment Decisions & Outcomes Stressing Out About Money “I have a high tolerance for […]

[…] Further Reading: How Framing Affects Investment Decisions & Outcomes […]

[…] View (Compounding My Interests) see also How Framing Affects Investment Decisions & Outcomes (Wealth of Common Sense) • How Much the Presidential Candidates Raised from Real People (Bloomberg) • ‘B.S. […]

[…] How Framing Affects Investment Decisions & Outcomes (awealthofcommonsense) […]

[…] Further Reading: How Framing Affects Investment Outcomes & Decisions […]