“The emotional tail wags the rational dog.” – Daniel Kahnemen

I wanted to go into more detail on one of the themes I picked up on from the Morningstar Conference, which dealt with the current mood of investors.

Like the process of investing, gauging investor sentiment is more of an art than a science. You can see that from reading a few financial headlines each week. We hear about the number of bulls and bears in the latest survey data, mutual fund flows, the amount of cash investors are carrying in their portfolio, the number of households investing in the stock market or a fear and greed index.

It’s easy to build a narrative around these data points, but they often tell conflicting stories and it’s very difficult to to tell how much noise they contain.

At the most basic level, there are really only three variables that drive stock market performance over time:

- Company earnings growth.

- Dividends per share.

- What investors are willing to pay for those earnings and dividends.

Number three on the list is generally called the price to earnings ratio, but in reality it’s a measure of the emotional state of investors. How are they feeling about stocks? Is the outlook positive or negative? Is there more demand to get in or to get out?

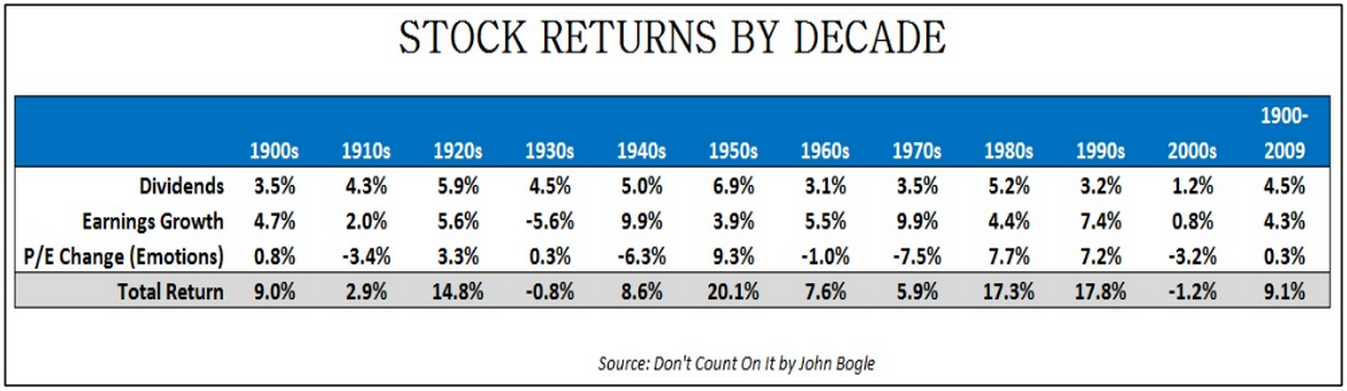

Here are those three performance drivers going back over a hundred years:

Dividend yields and earnings growth have been relatively stable, but you can see the emotions of investors have swung wildly at times from decade to decade between optimism and pessimism.

Sentiment indicators can be extremely confusing in the short-term, but even over decade-long periods they don’t make much sense:.

- Company earnings dropped over 40% in the 1930s, but P/E multiples actually expanded marginally.

- Earnings snapped back in the 1940s, but investors weren’t willing to pay for that growth. Stocks still did reasonably well.

- Then in the 1950s optimism reigned as emotions were the biggest driver of performance. Earnings growth was more subdued but investors were willing to pay up for them.

- It was back to 10% growth in the 1970s, but inflation caused a huge drop in the P/E ratio.

- Growth was decent in the 1980s and 1990s but investors bid up stocks in a big way.

- Those emotions reversed in the 2000s as stocks and valuations finally came back down to Earth.

These emotional swings are what make predictions on the markets so difficult. You can assign reason or context for the changes in emotions for each of these periods, but they only make sense with the help of perfect hindsight. Even then it’s difficult to know which factors were really driving investor attitudes towards risk.

You could build the most accurate models to forecast company dividend yields and earnings growth and still be completely off about the future direction of the markets.

Guessing how investors will feel about the markets is really the only way to know which way they will move in the future and this is an impossible task to perform with any precision.

That’s why it’s always important to put into perspective the factors that are within your personal control and those that are out of you hands.

We can’t control the emotions of other investors, but we do have control over our own actions and impulses and how we react to the changes in the financial markets. Former basketball coach Bobby Knight summed this up nicely:

“Your biggest opponent isn’t the other guy. It’s human nature.”

Subscribe to receive email updates and my monthly newsletter by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs

[…] Checking in at the Morningstar Investor Conference. (A Wealth of Common Sense, ibid) […]

[…] Investor Sentiment […]

[…] performance is based on emotions, trends, fundamentals, supply & demand and sentiment (see here). Higher valuations tend to lead to lower future returns, but there are always outliers in the […]