“Since the basic game is so favorable, Charlie and I believe it’s a terrible mistake to try to dance in and out of it based upon the turn of tarot cards, the predictions of “experts,” or the ebb and flow of business activity. The risks of being out of the game are huge compared to the risks of being in it.” – Warren Buffett

Investors are always citing the famous Buffett quote on fear and greed when making the point that they are a contrarian just like the Oracle. The problem is that Buffett doesn’t necessarily try to be a contrarian at all times. Sometimes he buys, sometimes he sells, but most of the time he does nothing. He is only really a huge contrarian at the extremes. The following quote illustrates this nicely:

Four or five times during their lifetimes, investors will see incredible opportunities in equity markets … they have to have the mental fortitude to jump in when most are jumping out.

These incredible opportunities he is talking about come around maybe once a decade. The rest of the time the market either trends higher or fluctuates in a sideways pattern. Those are the times when you’re better off not over-thinking things.

Even when Buffett was urging caution in 1999, he wasn’t telling everyone to sell out of the market and go to cash (although I bet he wishes he had). And in late-2008 he wasn’t telling everyone to lever up and go all-in on a buying spree. He was helping investors define their expectations for lower future returns in 1999 and higher future returns in 2008.

It may not seem like it, but the markets aren’t always just about to crash or shoot higher. It’s not always a peak or a valley. Roughly 5% of all trading days in the market close with a new high, so you could be waiting for a while if you consistently try to pick the top. It’s not so easy finding the bottom on the way down either.

Of course the financial media doesn’t do you any favors on this matter. This was the most viewed story on MarketWatch for a number of days a couple weeks ago:

Good thing that black-swan warning is done by mid-April. A crash would really put a damper on my summer plans. Notice the date of that story and then see this headline that was put out less than two months earlier from the very same author:

OK, so the strategy laid out here was to get in before the huge bull market from February to March and then get out before that 99.9% risk of a crash happens between March and April. Got it. Sounds like a wonderful way to run my retirement fund. But only 99.9% confidence in a crash? I need to see more assurance from your forecasting skills.

Hopefully you are well aware of the fact that you need to ignore this type of attention-grabbing headline writing that tries to play off of your emotions to get page views (unfortunately it worked).

Markets rise and fall. They always have, always will. Rarely do the short-term returns come anywhere near the long-term results. When you look back at the long-term historical 8-10% returns in stocks, that average includes not only the gains but the the losses too. It’s not 9% a year because you were able to nail more tops and bottoms than you missed. It’s 9% a year, warts and all.

By constantly trying to pick the perfect moment to go all in or all out you run the risk of a severe case of decision fatigue. Increasing the number of wholesale moves you make with your investments will only increase your stress level and the amount of mistakes in your portfolio.

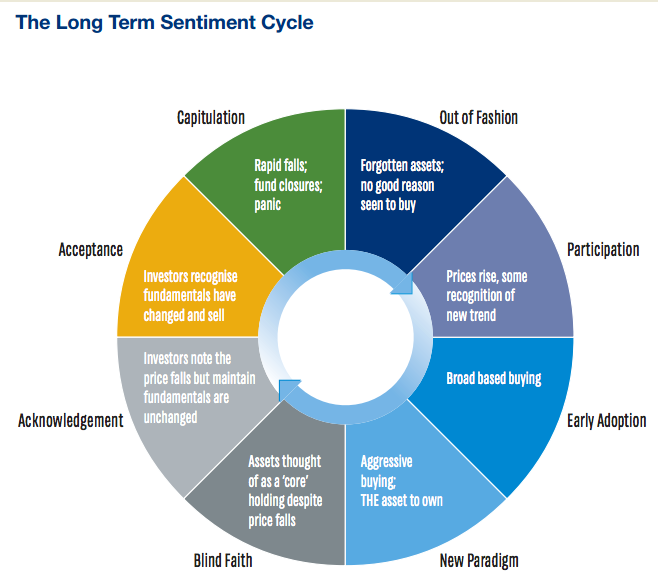

Since investing is more of an art than a science, sentiment plays a big role in determining how these things play out. I like this chart that explains the actions of investors at various stages of the sentiment cycle (hat tip @ReformedBroker):

We’re not always in the Capitulation (time to buy) or New Paradigm (time to sell) stages of the cycle. Thinking like that is a great way to run a whipsawed portfolio that you’re never quite comfortable with.

You can’t use this idea to make precise investment decisions, but it shows that you don’t have to try to be a contrarian at all times. It can take a while to work through the different steps in the process. Doing nothing works just fine the majority of the time.

Source:

MarketWatch

Further Reading:

How to think about new highs in the stock market

[widgets_on_pages]

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs

[…] Contrarian […]

Great post, AWOCS.

Trying to be a contrarian all the time can result in terrible investing strategy and lower returns. Investors, time and again, fall into the trap of timing the market and losing more of their nest egg.

regards

R2R

Thanks. It’s a balancing act between getting caught up with the crowd and being a contrarian at times.

That’s a big change in market sentiment by that author in such a short time. I really wish that all these forecasters would have to be held accountable for all of their predictions. How in the world can you believe that you should be going all in on stocks and then about 1.5 months later you think investors should be running for the exits? I could maybe understand that if the markets doubled or tripled in a 1 month span, but seriously it was what probably a 3% move? That’s one of my biggest gripes with the financial industry as a whole. Plus you’ll have the research arms of brokerages issue ratings to try and move the share price of certain stocks a certain direction. They change their sentiment way too often too. It’s best to just ignore 99.9% of the mainstream news outlets because listening to it is hazardous to your wealth.

I typically try to make a purchase or two each month and build a bit of a cash position when I just don’t see that many opportunities. It’s not always all in or all out, the majority of the time it’s best to selectively invest and continue to look for bargains.

Right, gaining page views is much more important for some of these sites than actual functional advice. I do think there are better sources out there now than in the past, but there is just so much information that it’s hard to find the right ones.

[…] You can’t always be a contrarian by A Wealth of Common Sense […]