“Instead of concentrating on the central issue of creating sensible long-term asset-allocation targets, investors too frequently focus on the unproductive diversions of security selection and market timing.” – David Swensen

“One of the things you learn about asset allocation is that the unemotional defeat the emotional over time by fading their highs and lows, their greed and fear, on a consistent basis.” – Josh Brown

Common sense reader mailbag: You keep stating how important asset allocation is for my investments. What do I actually have to know about the different asset classes to set my weights? Am I supposed to be able forecast future performance for stocks and bonds?

Asset allocation really comes down to four these questions:

(1) How many and which specific asset classes should I own?

(2) How many sub-strategies within each asset class do I want to own?

(3) How much risk am I willing and able to take?

(4) How do I implement and turn this information into a portfolio?

What follows is my take on each to help you understand asset allocation in more detail and why I think it’s important.

(1) How many and which specific asset classes should I own?

At a general level, most investors will be fine owning a simple mix of stocks and bonds in their portfolios. Stocks allow you to earn a piece of the profits generated from the business world. Bonds give you the predictability of fixed cash flows through interest payments.

Here are some of the basics you need to know: the long-term historical returns and risk characteristics, how mean reversion works in practice, what your goals are and how that all fits within your risk profile and time horizon.

Understand that risk and return characteristics are not necessarily set in stone. Stocks and bonds can both become overvalued or undervalued.

Here’s the very sharp Larry Swedroe on the topic of valuation and asset allocation:

Smart investors know that while there’s little to no evidence that you can successfully use valuations to time the market, valuations do matter. And they matter a lot in terms of predicting the mean expected return you can expect from your portfolio. Higher valuations predict lower returns and vice versa. And since valuations matter, there’s no way to decide on an asset allocation plan without forecasting returns…Smart investors also know to avoid the mistake of treating the expected return as anything more than the mean of a very wide dispersion of potential outcomes.

You must admit that you have no idea where the markets are going today, tomorrow or in the next month. Don’t try to forecast the short-term, but utilize a historical perspective based on results and valuations to shape your views of the present.

Markets can fluctuate between a state of overvaluation and undervaluation. It’s just very difficult to make large scale buy and sell decisions based on valuations because they tend to go further than we think they will in both directions.

The benefit of dollar cost averaging into the market by spreading out your contributions is that you don’t have to make those predictions.

Returns could definitely be worse or even different in the future. You just don’t want to have an investment plan based entirely on your forecasting abilities. You want it based on a disciplined process. Think rules-based over forecast-based.

The general trend has been up but trying to forecast that trend over the short-term is impossible.

(2) How many sub strategies within each asset class do I want to own?

Since we can’t predict the exact returns of the stock and bonds markets it makes sense to spread out your investments by diversifying within each asset class to take advantage of a broad range of markets and geographies.

A very diversified portfolio includes large-cap, mid-cap, small-cap, international, emerging markets stocks and both global government and corporate bonds. I also think it make sense to add REITs to a portfolio to gain access to the commercial real estate market which is roughly the same size as the stock market (about $15 trillion).

You can keep things very simple by choosing total market index funds or choose one fund for each sub strategy to take advantage of reversion to the mean by rebalancing at least once a year.

(3) How much risk am I willing and able to take?

Risk means different things to different investors. For most of us, with a long time horizon for our retirement portfolio, the biggest risks we face are not reaching our long-term goals and the permanent loss of capital.

It’s easy to forget about our time horizon when markets make large moves in either direction. Here’s John Bogle in this subject:

“In this decade, the heavy lifting will have to be done by stocks. If stocks deliver 7 percent, you’ll have 100 percent return in 10 years. And there will be bumps! I don’t want to deceive anyone. I can guarantee that there will be at least two or three 20 or 30 percent bear markets in that time frame. Just assume them. When they happen, just say, ‘I knew that.'”

“It’s foolishness to think you can beat the market. There are only two things working here: How much did it cost to get into the market, and how long are you in? If you’re investing for a lifetime-and you should be, saving for retirement and educating your kids along the way-if you’re 20 years old now, you should be thinking 60 or 65 years as your time horizon.”

Your risk of loss should decrease as your time frame increases, but that still doesn’t make your job any easier in the short-term when you see big losses. That’s why a consistent and automated process is so important so you don’t have to make decisions when emotions run high.

Behavior can be a blessing or a curse depending how you manage your emotions.

(4) How do I implement and turn this information into a portfolio?

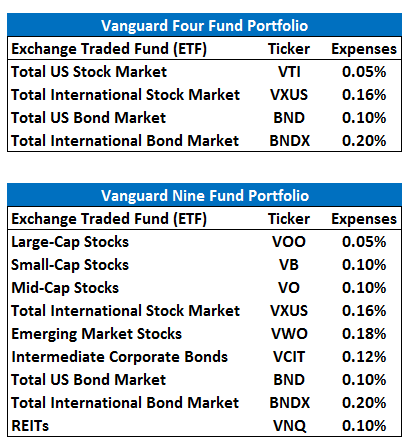

Here are two examples of some common sense ETF portfolios along with the corresponding fees:

The first portfolio offers broad diversification in a minimal number of funds. The second portfolio offers more diversification at the sub-strategy level. These portfolios may not be a perfect fit for your current situation but they should give you an idea of how I look at structuring a simple low-cost asset allocation.

Obviously, you would have to choose the weights for each based on your risk tolerance and time horizon (if you aren’t invested with Vanguard you should be able to find similar funds across the various fund companies in both ETFs and mutual funds).

This is your money and no one cares about it as much as you do, so you have to go with what you are comfortable with, regardless of what I think.

There’s not a one-size-fits-all asset allocation for every investor since everyone has unique circumstances. If you focus on your process, think long-term, keep your costs low, and have a broad diversification to spread your risks you should do better than most.

Remember that your asset allocation choice needs to be sound, but it will probably change over the years as your circumstances change. So it makes sense to revisit this exercise on a periodic basis to make updates as you go.